America's biggest universal basic mobility experiment is taking place in L.A.

trekandshoot // Shutterstock

America’s biggest universal basic mobility experiment is taking place in L.A.

LA Metro E line train pulls into Boyle Heights with Downtown LA in the background

In May of last year, the Los Angeles Department of Transportation and LA Metro launched the biggest Universal Basic Mobility experiment ever attempted in the U.S., giving 1,000 South Los Angeles residents a “mobility wallet” — a debit card with $150 per month to spend on transportation.

The catch? Funds can be used to take the bus, ride the train, rent a shared e-scooter, take micro-transit, rent a car-share, take an Uber or Lyft, or even purchase an e-bike — but they can’t be spent on the cost of owning or operating a car.

The year-long pilot, ending in April, has the dual goals of increasing mobility for low-income residents and reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

It’s a radical experiment based on a simple idea: People know what they need. Give them the money to go where they want to go, and they will improve the quality of their lives.

It’s the biggest experiment in Universal Basic Mobility in the U.S., but it is not the first.

“Mobility wallets are catching like wildfire,” Mollie D’Agostino, executive director of the new Mobility Science, Automation, and Inclusion Center at UC Davis, told Next City. In California alone, Oakland, Bakersfield and Stockton (the site of a famous Universal Basic Income experiment that spurred an explosion of guaranteed income pilots and policies) have all implemented UBM pilots, as has Pittsburgh.

How L.A.’s mobility wallet pilot works

The pilot is targeted at low-income residents of South L.A. who don’t have access to a car. According to LA Metro, 80% of participants are enrolled in a financial assistance program, over 60% regularly take public transportation, 40% live in a non-car household and 50% don’t have a driver’s license.

For the first phase, in addition to online enrollment, Metro partnered with 20 community-based organizations to get the word out about the program.

“[With] eight of those, we went on to do actual in-person workshops with them at their community centers, at their churches — literally, a few of the workshops, we were actually signing up people in the pews,” says Avital Shavit, senior director at LA Metro.

Participants receive a debit card that is loaded with $150 every month for a full year. Funds that are not spent are rolled over to the following month. Although the card functions like a normal debit card, the money can only be spent on pre-approved transportation expenses — for example, loading an LA Metro TAP card, buying an Amtrak ticket or paying for a taxi.

Participants have also used the wallet in creative and resourceful ways, including saving up the monthly funds to purchase an e-bike and buying a subscription to an e-scooter platform.

The mobility wallet is part of a larger Universal Basic Mobility pilot, funded by almost $18 million from the California Air Resources Board and the City of Los Angeles. In addition to the mobility wallet, the pilot includes an e-bike lending library, an expansion of BlueLA, an electric vehicle car-share program and the installation of electric vehicle charging stations, among other initiatives.

There are currently three phases to the mobility wallet pilot, with future phases dependent on funding. The first phase is funded by $2.5 million from CARB and $2 million from the city. In the second phase, starting summer 2024 and funded by $4 million from the Southern California Association of Governments, the program will open up to 1,000 new South L.A. participants as well as 1,600 participants recruited from L.A. County as a whole. Phase three is already in the works: Metro is working with Caltrans to secure federal funding to continue the pilot.

Not all agencies have access to the same resources or funding, but LA Metro is hoping to expand access to these types of programs to other regions and agencies.

“We’re actually working with Caltrans to look at how we might do a statewide procurement for prepaid cards as a mobility wallet, so that it’s not just LA Metro or the city of L.A., but any agency across the state — that maybe anywhere in the nation could have the same purchasing power for these cards,” says Shavit.

![]()

LA Metro

How the pilot is going

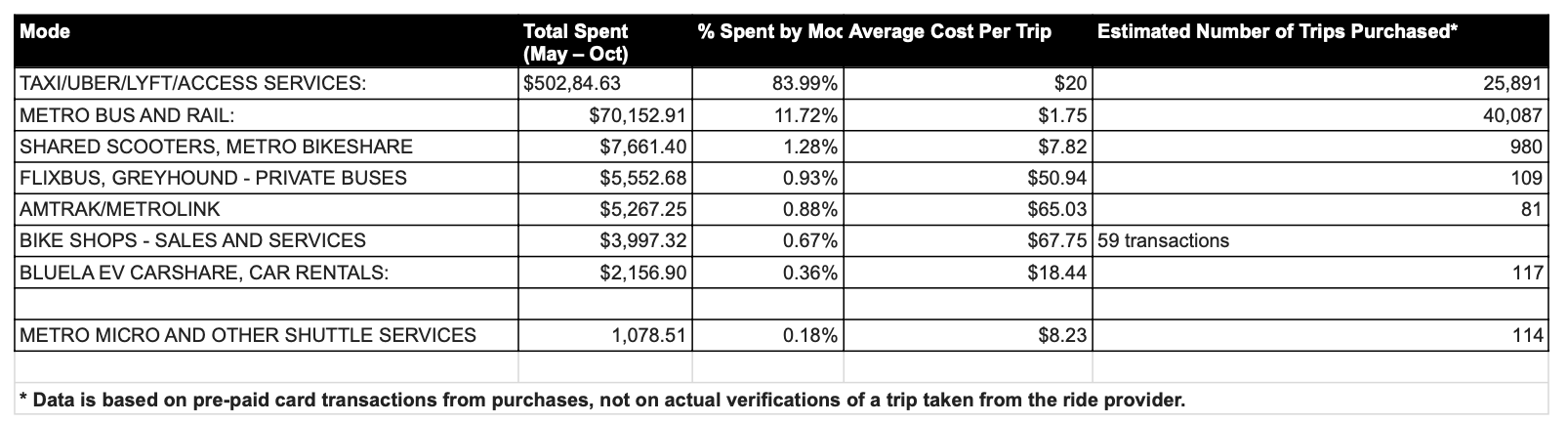

Data for the first six months of L.A.’s universal basic mobility pilot.

According to data from the first six months of the program, the majority of estimated trips taken have been on public transportation (40,087 trips out of 67,379). The majority of the funds (about $500,000) have gone to ride-hailing or taxi services like Uber and Lyft, for about 26,000 trips at an average cost of $20.

“Initially, we were surprised that there was so much use of Uber and Lyft,” says Caroline Rodier, a researcher at the UC Davis Institute of Transportation Studies. “But on the other hand, it makes sense, because there is pretty good transit service in that area.”

According to Metro, participants are taking the bus or train during normal commute times and taking ride-hailing services early in the morning or late at night, indicating that participants are using options like Uber and Lyft when transit options are less available. Another concern is safety — access to ride-hailing might provide a safer option.

After 37-year-old South L.A. resident Rebeca Hernández’s car broke down, she could no longer pick up her mother who works at a laundromat late into the night.

“The MW [mobility wallet] card has been very helpful to us. I use it to take the bus or train to DTLA and the supermarket,” says Hernández in an interview with Metro’s blog, The Source. “My mother uses it to take a taxi and come back home safely.”

The program has not been without its growing pains. Giving people money costs money.

“You would think it would be easy to give people a mobility wallet, but it’s not,” says Rodier. “There are a lot of administrative costs. And when you’re distributing that kind of benefit, you want to really keep your administrative costs low.”

One of the challenges is making sure that each eligible vendor can accept the mobility wallet as a form of payment. The card uses merchant codes on the backend to control which businesses and agencies are eligible.

Getting around without a car can still be challenging in car-dominated Los Angeles, even in transit-rich areas like South L.A. For any Mobility as a Service (MAAS) program to work, cities need a reliable transportation network that doesn’t require driving a privately owned vehicle.

What does the future hold?

The mobility wallet pilot, which Shavit says might be supported throughout L.A. County to prepare for hosting the 2028 Olympics, isn’t just about increasing transportation equity. It’s also about how people pay for transit.

Currently, LA Metro customers must use either cash or purchase a TAP card to ride the bus or train. But what if they could use a credit or debit card?

“This next year, our current large fare payment contract is actually expiring,” says Shavit. “We have a once-in-a-generation opportunity to look at a new fare system contract.”

Another long-term possibility is integrating different programs for income-qualified users onto a single card, so that people don’t need to juggle multiple cards to access transportation, health, food or other benefits. There is a nationwide push to make electronic benefit transfer (EBT) cards open loop, or chip-and-pin, versus the current closed loop system.

But integrating federal, state and local programs is a broader challenge — a “golden goose,” according to Shavit — that Metro doesn’t have the power to implement.

As cities strive to shift people from cars to greener modes of transportation, making it easy and convenient to pay for a wide range of transportation options is a necessary hurdle. D’Agostino envisions that in the future, people could choose to purchase a mobility wallet instead of a parking pass or a highway pass.

“The wayfinding aspect of Mobility As A Service is pretty figured out,” she says. “But that payment integration piece [is] a real tricky part.”

This story was produced by Next City through its Equitable Cities Fellowship for Social Impact Design, which is made possible with funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, and reviewed and distributed by Stacker Media.