From frozen waffles to onions: How recent recalls highlight the range of food poisoning

NurPhoto // Getty Images

From frozen waffles to onions: How recent recalls highlight the range of food poisoning

A close up of romaine lettuce.

From E. coli traced to slivered onions on McDonald’s Quarter Pounders to mass recalls of frozen waffles due to listeria risk, foodborne illness seems ever-present in the headlines. According to the Food & Drug Administration, foodborne illness affects 1 in 6 Americans every year—that’s 48 million cases annually.

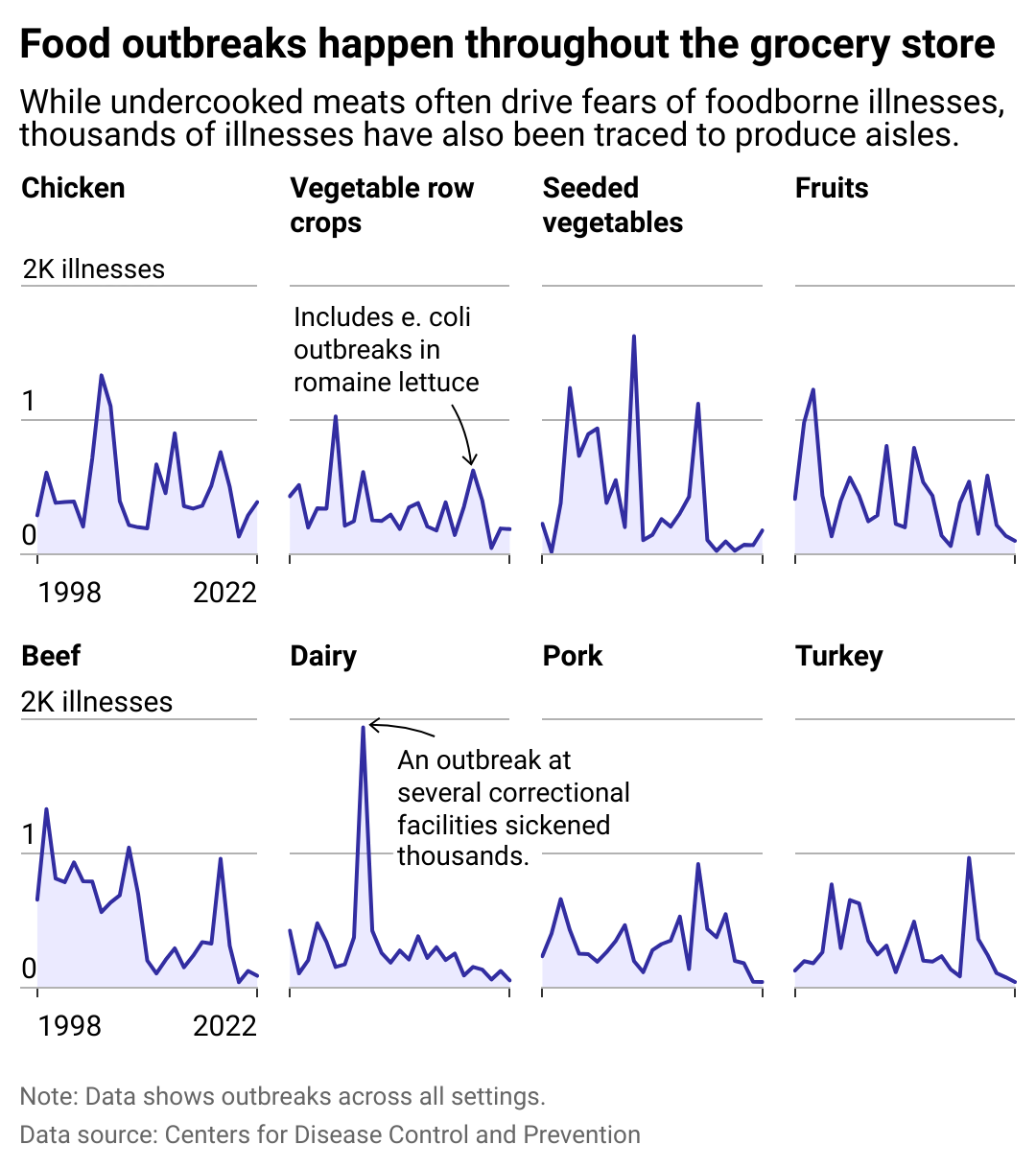

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows that Americans’ risk of getting sick from foodborne germs is back to pre-pandemic levels, making foodborne illness a significant public health threat in the U.S. VNutrition used CDC data to look at foodborne illness outbreaks across the top food groups since 1998.

Foodborne illness is caused by the consumption of food or water contaminated by bacteria, viruses, parasites, or toxins. Symptoms can be as mild as cramps and a bit of diarrhea to life-threatening situations like respiratory failure and meningitis. The young, older people, and immune-compromised individuals are most at risk of serious complications, but some of the more serious pathogens are threats to even the healthiest.

Are more people getting sick or do we just have better tools to identify contaminants and more efficient methods to alert consumers of possible risks? The answers aren’t clear on any of those questions but what is known is that climate change appears to impact the growth of foodborne pathogens.

So how do people avoid food poisoning and encountering foodborne illness? Most know that consuming unclean water or eating improperly prepared meat enables the transmission of bacterial infections, but in many of the recent outbreaks, like the McDonald’s case, the culprits have been fresh vegetables and nonmeat items.

Leafy vegetables like lettuce, spinach, and cabbage are among the top sources of foodborne illness in the U.S., according to the CDC, which studied the nation’s most common sources of foodborne illness from 1998 to 2008. The problem is that unlike meat, fruits and vegetables, especially leafy greens, are often consumed raw. Thus any harmful bacteria that has contaminated those veggies—such as E. coli, salmonella, and listeria—doesn’t get eliminated by cooking. Still, the health benefits of eating vegetables, especially leafy greens, outweigh the risk of possible contamination. Proper preparation and handling is key.

![]()

VNutrition

Most common foods linked to foodborne illnesses

Multiple line charts showing food outbreaks happen throughout the grocery store. While undercooked meats often drive fears of foodborne illnesses, thousands of illnesses have also been traced to produce aisles. From 1998 to 2022 top categories include beef, chicken, fruits, pork, seed vegetables, vegetable row crops, turkey, and dairy. Dairy is partially driven by a major outbreak at several correctional facilities in 2006.

From this chart, it’s clear that alongside fruits and vegetables, another frequent, nonmeat-related cause of foodborne illness is dairy products—soft cheeses being among the most frequent culprits (which is why pregnant women should avoid them).

A CDC study on listeria outbreaks from 1998 through 2014 attributed 30% of the cases to soft cheese, which due to its higher moisture content, is a better host for the pathogen than hard cheese. Plus, listeria can still grow at refrigerated temperatures, persisting in cold storage (and freezers) and transmitting to other foods in an open environment like a deli case.

What can be done to limit exposure to contaminated foods? One measure that’s helped is the Food Safety Modernization Act, passed by Congress under the Obama administration in 2011. This law—the most comprehensive piece of food safety legislation made since 1937—shifts the Food and Drug Administration’s food-safety focus from responding to preventing food contamination by creating science-based prevention controls across the food supply.

Part of the reason that foodborne illness was more prevalent in 2018 than in 2017 is that more infections are diagnosed thanks to testing procedures this legislation put into place—the FDA’s ability to identify and track pathogens back to the source has greatly improved.

It’s necessary to have regulatory agencies helping to ensure food safety, but alongside that are a host of safety measures individuals can take at home.

Stay up to date on recalls via the USDA’s website, which details current contamination concerns and the products and areas affected. The best way—and unfortunately, the most time-consuming—is to eat only foods prepared and cooked at home. According to CDC data, 64% of foodborne illness incidents were attributed to dining out.

But even for those who cook at home, there’s often a reliance on prepackaged or prepared foods. Processing fresh fruit and produce into ready-to-eat products increases the risk of contamination because it breaks the natural exterior barrier of the produce, say a cantaloupe’s rind or an apple’s skin, which might contain lingering pathogens or pesticides. Washing all fruits and vegetables and eating them as soon as they are cut (or, of course, cooking them, if that’s appropriate) helps reduce the risk of contamination.

Still, the health benefits of eating fruits and veggies—in any form—outweigh the possible risk of exposure to a foodborne illness. A simple rule of thumb when it comes to avoiding nonmeat-caused foodborne illness is to cut out the major offenders—soft cheeses from unpasteurized milk, bagged or packaged salads with spoiled leaves, and raw, pre-cut fruit and vegetables.

The best practice for preventing foodborne illnesses for all foods, including meat, is the CDC’s four steps to food safety: clean, separate, cook, and chill. Wash hands, surfaces, utensils, and fruits and vegetables. Keep raw meats separate from other foods and use a specified cutting board for meat instead of the one used for vegetables. Cook foods to the right temperature. And finally, refrigerate perishables within two hours.

Story editing by Carren Jao. Additional editing by Kelly Glass. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

This story originally appeared on VNutrition and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.