Indigenous data warriors and the ongoing fight for data sovereignty

John Pepion // Urban Indian Health Institute

Indigenous data warriors and the ongoing fight for data sovereignty

A colorful illustration of a person at a computer that reads Decolonize data with handwritten data entries as a background.

Dr. Desi Small-Rodriguez calls her traveling data science lab her “Data War Pony.” It’s a huge trailer—a classroom on wheels equipped with computers and software, wrapped with ledger art by Dakota artist Holly Young. Small-Rodriguez, researcher, data advocate, and professor, rolls up to tribal communities in the lab (by invitation) to support the collection and analysis of data.

The Data War Pony is instrumental to Small-Rodriguez’s Data Warriors Lab, which carries out work “by Indigenous Peoples for Indigenous Peoples on tribal lands,” she explained in an email to Stacker. These efforts include collecting and analyzing all sorts of data, such as language repositories, health assessments, demographic and economic surveys, and even fish counts.

Small-Rodriguez is a citizen of the Northern Cheyenne Nation and Chicana, as well as an assistant professor of Sociology and American Indian Studies at the University of California, Los Angeles. She is also part of a growing renaissance of Native American “data warriors.”

American Indians and Alaska Natives face systematic undercounting, inaccuracies, and exclusion from data gathering, leading to a loss of resources. Stacker conducted interviews, consulted research, and explored how Indigenous data warriors are fighting for data sovereignty: the right and ability of tribes to develop their own systems for gathering and using data.

A relatively small population compared to the U.S., American Indians and Alaska Natives are excluded from data collection due to collection errors and small sample sizes, but also because the very systems used to count Indigenous peoples are built on inequity and a misunderstanding of Indigenous populations.

There is no statistical data standard to govern the collection and reporting of AI/AN population data across federal agencies, nor is there a mandate for state or federal agencies to collect race/ethnicity information.

![]()

Carren Jao // Stacker

Exclusion from data is ‘data genocide’

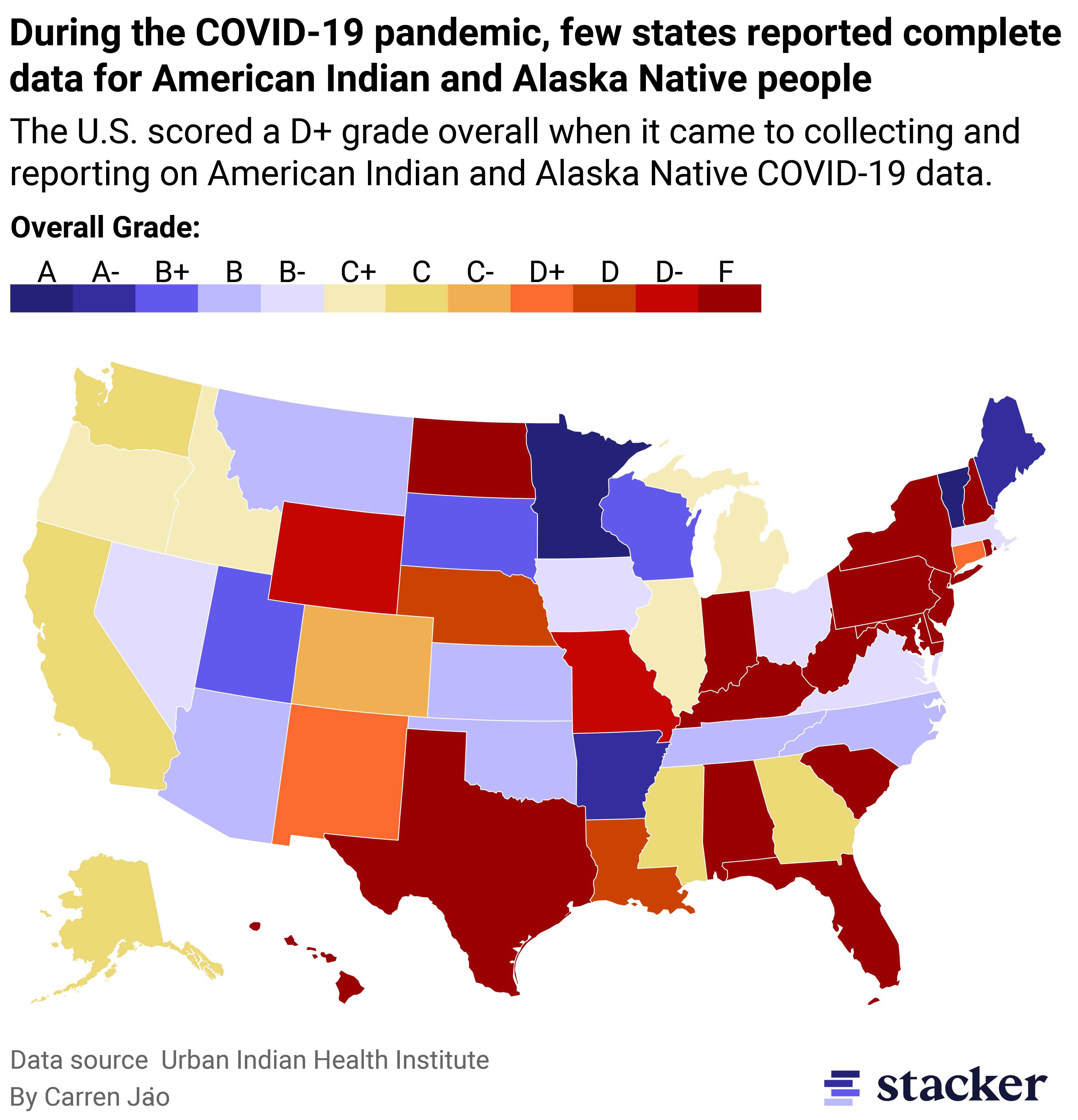

Map showing that during the COVID-19 pandemic, few states reported complete data for American Indian and Alaska Native people. The U.S. scored a D+ grade overall when it came to collecting and reporting on American Indian and Alaska Native COVID-19 data.

Communities can’t get the resources they need if there’s inaccurate data—or no data at all—to show how they are faring. At its worst, this exclusion from data is a practice Small-Rodriguez and other Indigenous scholars consider a form of “data genocide.”

Take the gathering of race and ethnicity data in the COVID-19 pandemic as an example.

Abigail Echo-Hawk, an enrolled citizen of the Pawnee Nation of Oklahoma, is also a data warrior in this growing revolution. She is the executive vice president of the Seattle Indian Health Board and director of the Urban Indian Health Institute. As part of its work to decolonize data, UIHI looked specifically at COVID-19 racial data collected and analyzed during the pandemic to create a national Data Genocide Report Card.

AI/AN populations suffered disproportionately from COVID-19. According to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Reports, which relied on a limited number of participating states, AI/AN communities were infected with COVID-19 3.5 times more often and died nearly twice as often as non-Hispanic white people.

The report noted that half of the COVID-19 cases reported as of Sept. 16, 2020, were missing race and ethnicity data altogether. It gave the U.S. an overall grade of D+. This lack of data prevented AI/AN populations from receiving comparable resources to fight the disease.

“Wherever we are not in the data, that means we are not getting the resources that are mandated in our treaties,” Echo-Hawk explained in an interview with Stacker, referring to the responsibility of the U.S. government to protect tribes and provide resources. Given that Indigenous populations are so often at risk in terms of social determinants that lead to health consequences, such as poverty and food insecurity, having accurate data is critical.

In another example, when the CDC published maternal mortality rates in 2021, the report left out American Indians and Alaska Natives “because they said they didn’t have enough data,” according to Echo-Hawk. “They could have used another statistical technique in order to aggregate multiple years.”

Instead, when Congress discussed the findings, American Indians and Alaska Natives were “just left out altogether, even though the data would have shown very high incidents of maternal mortality” in AI/AN populations, said Echo-Hawk.

For American Indians and Alaska Natives, being left out of data is nothing new. Indigenous peoples have even been coined as an “Asterisk Nation” by the National Congress of American Indians because, instead of data, American Indians and Alaska Natives are so often excluded and displayed merely as an asterisk.

While being repeatedly left out of the national conversation is hurtful and inaccurate—like when CNN used the term “something else” to refer to voters who did not identify as white, Latinx, Black, or Asian on election night 2020— it also has profound funding implications for tribes.

Census counts are used to calculate federal funding formulas and vital services allocations to American Indian tribes. For example, in fiscal year 2022, the Department of Housing and Urban Development distributed $772 million to tribes through the Indian Housing Block Grant, an amount determined using Census population data.

By the Census Bureau’s own admission, the 2020 Census, like the 2010 Census before it, undercounted American Indians and Alaska Natives. According to the Census Bureau’s Post Enumeration Survey, the 2020 Census undercounted American Indians and Alaska Natives living on reservation lands by an estimated 5.6% (up from 4.9% in the previous Census).

“Thousands and thousands of Northern Cheyenne were undercounted in the Census,” Small-Rodriguez said, referring to her tribe. “That in itself is an act of erasure and genocide. And that is the norm.”

Small-Rodriguez worked on the Census National Advisory Committee in the lead-up to the 2020 Census and is still working on connecting tribal enrollment records and government agency records. However, sharing that data is tricky because tribes are sovereign nations.

Small-Rodriguez wrote in an email: “It requires a lot of trust between tribes and the federal government though—which we know is hard to come by—because tribes would essentially need to turn over their enrollment data with tribal citizen names, DOB [dates of birth], and other confidential information in order to construct a big data set…”

The ‘purposeful erasure’ of Indigenous data

Echo-Hawk calls the numerous examples of “purposeful erasure” not an accident of data science, but a virus built into the system. According to the UIHI: “…the scarcity of data on AI/AN is not by chance but rather a continuation of systemic and repeated attempts at elimination.”

The exclusion of Native Americans from data goes back to the founding of this country.

Article 1, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution mandates a census every 10 years to determine congressional representation and the allocation of resources. But the U.S. government explicitly excluded American Indians for more than 100 years until the passage of the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act.

Hundreds of years of federal policy intentionally and violently excluded and marginalized Indigenous peoples. The U.S. removed Native Americans from their homelands, forced them onto reservations, into the boarding school system, and subjected them to oppressive assimilation policies by the federal government.

For example, the design of the 1887 General Allotment Act (or the Dawes Act) was to “civilize” Native Americans by taking land held in common by tribes and parceling it out to individuals. While it was allegedly to delineate Native American property rights, in reality, it was a massive land grab by settlers. Native Americans lost as much as 90 million acres of their land.

Blood quantum and statistics were designed to ‘break’ Native people

The U.S. has used the collection of vital statistics, like birth and death records, to “break Native people into fractions,” Echo-Hawk said. Since its implementation in the late 1800s, the U.S. government has used blood quantum, or proportion of Indian blood—in a similar manner as the U.S. used the “one drop rule” for Black people.

By measuring “Indian-ness” using fractions of Indian blood, the U.S. government hoped to eventually discount any Native American who failed to meet the minimum requirement. In doing so, the U.S. government sought to systematically use the construct of race so Native Americans would eventually breed themselves out.

“They broke Native people down by fractions to make Natives go away,” Echo-Hawk explained.

In her work with federal agencies, Echo-Hawk often comes across data that lumps AI/AN into an “other” category, undercounts tribes, and excludes anyone identifying as multiracial from data.

Without realizing the country created those systems “more than a hundred years ago to eliminate Native people so they didn’t have to fulfill their treaty responsibilities or allocate resources or land,” researchers continue working within these parameters “because that’s how they’ve always done it,” Echo-Hawk said.

That’s why Echo-Hawk is working to improve the collection and analysis of Indigenous data not just in public health and epidemiology, but also in other areas like criminal justice.

“The Violence Against Women Act says resources are supposed to be dedicated to those most impacted by crime. Native people are most impacted, but if there’s no data on it, the resources don’t have to be allocated,” Echo-Hawk said.

For example, tracking how many Indigenous women have been kidnapped or murdered is impossible unless information about race and tribal affiliation is collected in a culturally appropriate way.

In Washington state, Echo-Hawk worked directly with the King County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office to change how law enforcement officers gather information about victims and family members when a case is referred for prosecution. Law enforcement does not usually collect tribal affiliation data, but Echo-Hawk helped the county realize the vast holes in their data. They now share information with local tribes, a partnership she hopes to replicate nationwide.

Data collected in partnership with tribes, as opposed to extracted from them, “can make an active difference in the [Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women] crisis and in ending data genocide,” Echo-Hawk said.

On the other hand, data extraction done without the consultation of tribes deepens mistrust between data researchers and Indigenous peoples.

In 1989, for example, the Havasupai Tribe approached an Arizona State University anthropologist to assist the tribe with an epidemic of diabetes in their community. However, the blood collected from more than 200 tribal members was used to study schizophrenia without consent from the tribe. It took a legal battle to get the blood samples returned.

This misuse of the blood of tribal members underscores the importance of honoring the “history, culture, values, and wishes when engaging in research with that community,” particularly given the fact that blood holds unique cultural and spiritual value to the Havasupai, as the Center for American Indian Community Health laid out in a 2013 paper published by the American Journal of Public Health.

The Havasupai believe that in death, a person cannot pass to the next world unless all their possessions are buried with them. Keeping their blood samples in a laboratory would have prevented them from moving on spiritually. Furthermore, some tribal members chose not to seek treatment for their diabetes later in life due to the fear and mistrust stemming from the “diabetes project.”

Indigenous peoples have always been data gatherers

The Lakota and Blackfeet tribes made counts of tribal citizens, allies, enemies, wild game, and lodges on animal hides, Small-Rodriguez noted in “Building a Data Revolution in Indian Country,” her chapter in the 2016 book “Indigenous Data Sovereignty: Toward an Agenda.”

But what Indigenous peoples empirically used for survival became an instrument of colonization. It is telling that the U.S. government established the Bureau of Indian Affairs, responsible for “the civilization of the Indians” inside the War Department.

“Indigenous data engagement in the United States is inextricably tied to the subjugation of American Indians and federal policies of Indian extermination and assimilation,” Small-Rodriguez wrote.

Later, the U.S. moved the BIA to the Department of the Interior.

“Then, when they stopped classifying us as enemies, they now classify us alongside the parks and minerals. It’s parks, minerals, and Indians,” Small-Rodriguez said.

The ‘data revolution’ is gaining momentum

While the BIA is still housed within the DOI, the fight for data sovereignty is gaining new momentum.

“Now we are seeing a new generation in Indian Country who are really starting to take the initiative to do the work,” Small-Rodriguez said. She points to the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative launched by Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland in 2021.

Haaland, who is Laguna Pueblo, is the first Native American Cabinet secretary, and this initiative is quantifying the loss of Indigenous life in Indian boarding schools. While that work is ongoing, the DOI has already detailed, for the first time, that more than 500 Native American, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian children died attending Indian boarding schools in the U.S.

For data warriors like Small-Rodriguez, this report is a step in the right direction for data sovereignty.

“We have to have the data and put it in their faces so they can reckon with what they have done to us and our grandparents and our children. The power of data is to be able to be this mirror,” Small-Rodriguez said. “This is what you did to us, and you have irrefutable evidence now. Look at yourselves. And that’s how you start to dismantle and rebuild relationships.”

With that shared goal in mind, Echo-Hawk is working tirelessly to duplicate victories in data gathering and sharing across the country. She is also working to develop a technical and in-depth framework for best practices in data collection for use at large.

Meanwhile, Small-Rodriguez is planning a summit in 2024 for the U.S. Indigenous Data Sovereignty Network, which she co-founded. The gathering will bring together Indigenous peoples and allies leading the charge on this data sovereignty revolution, hashing out the priorities for Indigenous data governance in the U.S.

As Small-Rodriguez wrote, “All Indigenous data must start and end with Indigenous Peoples. Period.”

Story editing by Carren Jao. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.