Bank junk fees: Who gets hit and which institutions are the worst offenders?

fizkes // Shutterstock

Bank junk fees: Who gets hit and which institutions are the worst offenders?

young person looks irritated while looking over paperwork in front of laptop with windows in background

Tens of millions of consumers are hit with extra fees – often called “junk fees” – on everything from ticket purchases to home rental applications, costing billions of dollars each year. Eager Taylor Swift fans made the issue prominent last year: After competing for Swift’s Eras Tour concert tickets, they often found themselves at checkout facing unexpected “seller fees” and let ticket agencies, social media and Congress hear their frustration.

Even if you’re not spending hundreds of dollars on concert tickets, anyone with a credit card or checkbook is likely familiar with add-on or even hidden fees banks charge to their accounts. Consumer complaints against big-bank junk fees are rising and federal regulations are in the works, including new rules to limit checking overdraft penalties and credit card late fees. President Joe Biden has made bank fees a central issue for his administration as institutions collect billions from customers.

With financial fees in the spotlight, the ConsumerAffairs Research Team analyzed three years of Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) complaints to detail the worst fees, the most aggressive banks and whether proposed reforms can actually limit consumer pain.

Key insights:

- Americans angry enough to bring their bank fee complaints to a federal agency increased 66% between 2021 and 2023.

- Bigger banks earn the highest wrath, with Capital One taking the lead in the number of complaints.

- Credit card fees and interest rate hikes earn more complaints than checking or other bank fees.

- Younger, less affluent consumers are more likely to get hit by late fees.

- Some states have much higher rates of complaints per capita than others.

Behind complaints about banking fees is a deep exasperation. Susan, a Bank of America customer in Sicklerville, New Jersey, said she had to pay fees to close her account in November. Then a month later she received a notice that she owed more fees.

“I called customer service,” Susan wrote in a review at ConsumerAffairs, “and they said that if someone tries to change the account, it reopens. I said, ‘This is ridiculous.'”

Still, Susan was able to get the account closed again while on the phone, only to receive a letter from Bank of America one month later. “They are unable to complete my request,” she recounted.

“I now owe $182 in order for them to close. This is after I paid over $200 to close back in November.”

Cathy Mansfield, a professor of law at Case Western Reserve University and previously a policy analyst with the CFPB, says fees are indeed a large profit center for banks and are usually paid by the most vulnerable customers.

How big of a profit center? At its peak, Mansfield said, “annual overdraft fee revenue alone was an estimated $12.6 billion.”

Capital One leads the way

All financial institutions receive customer complaints about fees, but some get more complaints than others. In the last three years, Capital One — just the ninth largest bank and fourth largest in terms of credit card purchases — earned the most CFPB complaints about fees.

“I made a payment on my actual due date but was charged a $25 late fee because it did not post until the following day,” a Capital One reviewer from Burbank, California, said. “[The rep] informed me that I had assessed a late fee because I made my payment past the cutoff time on the due date.

“The customer service reps … all seem like they’ve gone through a rigorous ‘customer disservice’ training,” the reviewer added, recounting other fee disputes with Capital One.

Here are the top eight banks in terms of complaints, which account for nearly half of the customer complaints.

![]()

ConsumerAffairs

Well-known banks are most aggressive

table showing companies with the most complaints

Clearly, it’s the big banks that make the biggest targets for complaints. All but one of these are household-name institutions. Even the one that isn’t, Bread Financial Holdings, provides branded credit cards for well-known retailers.

JPMorgan Chase, the nation’s largest bank and largest credit card issuer, is only seventh on the complaint list, with less fee disgruntlement than other big banks.

Meanwhile, Bank of America proved to be the least responsive among leading banks to fee complaints, which the CFPB also tracks. It had the highest percentage of delayed responses to complaints – 7%. The average for all financial institutions is 2%.

ConsumerAffairs

Who pays the price, state by state

map showing junk fee complaints by state

When it comes to bank and card fees, Ben McLaughlin, U.S. president at Raisin, a savings platform, says not all consumers pay as often or as much as others. Generation Z pays more fees than baby boomers, he says, while Black and Hispanic consumers pay more than two times what white bank customers pay in fees.

CFPB data confirm his assertion. In a December 2023 report, the CFPB found the younger you are, the more likely you are to get hit with late fees. Income and education also play a role. “Those with a college degree are over 10 percentage points less likely to face a late fee,” the report states.

The ConsumerAffairs analysis found a dramatic difference in how frequently residents of different states file their complaints to the CFPB.

Washington, D.C.had the most complaints per 100,000 residents, at 13. Delaware was second, with 11 complaints per 100,000 people.

These rates are far higher than that of Puerto Rico (1.2 complaints per 100,000) North Dakota (1.5 complaints), and other less-populated states like Iowa, Montana, West Virginia and Wyoming (all between two and three complaints per 100,000). Only some of the large differences can be explained by demographics.

ConsumerAffairs

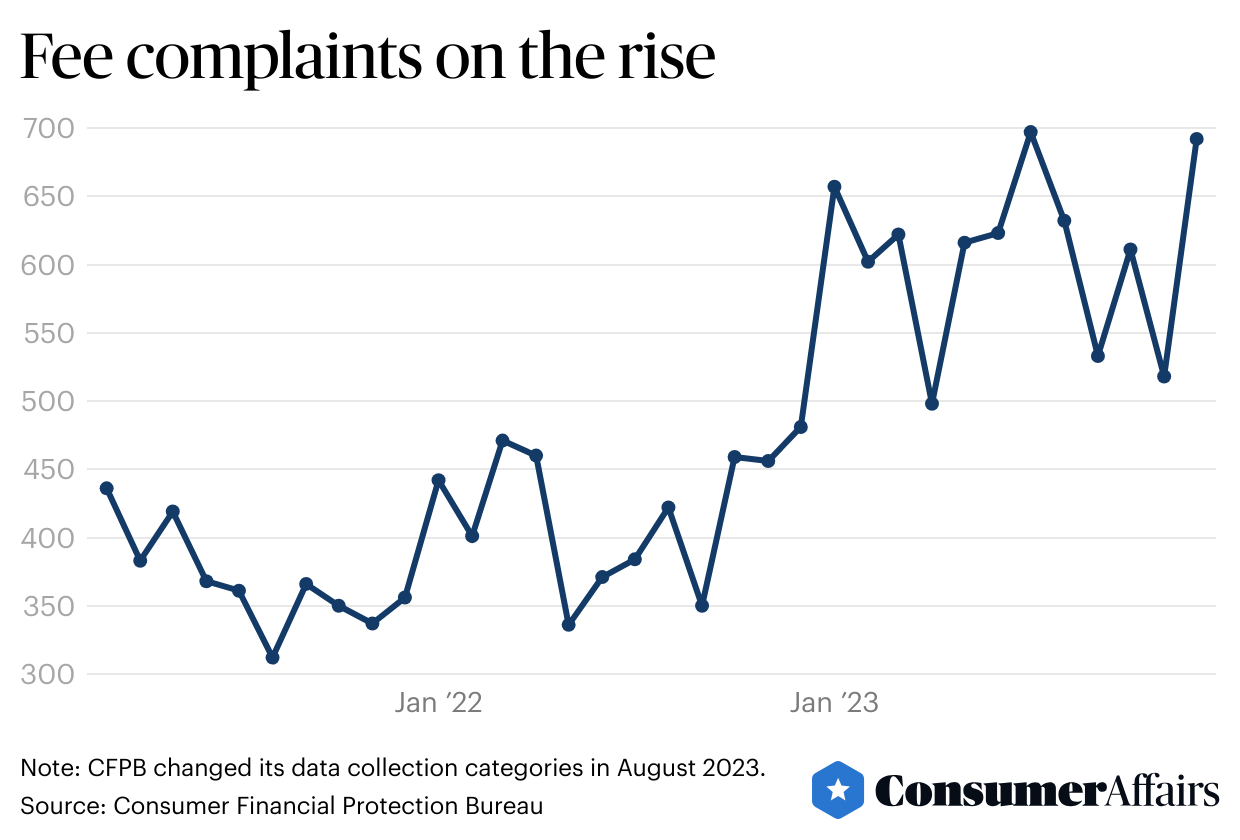

Dissecting the rise in complaints

graph showing fee complaints on the rise

What’s behind the overall 66% rise in fee complaints over three years? McLaughlin, the savings executive, believes the anger reflects the reality of dealing with massive financial institutions. “Bigger banks have gotten very creative at coming up with new fees, while also not passing along profits gained from high interest rates to customers,” he said.

Credit card fees. Along with prepaid cards, credit cards are the target of more than two-thirds of fee-related complaints. Some cards charge an annual fee. Most balance transfer cards – a tool for the faster pay-down of balances – charge a fee of 3% to 5% of the transferred balance. Nearly all charge a foreign transaction fee to compensate for currency differences. Consumers are advised to read offerings painstakingly when choosing a card.

Jennifer, of Jacksonville, Florida, is not very pleased with Aspire Visa’s fee system. “They just had the nerve to send me an email saying I may qualify for a credit increase of $250, but I would have to pay them a one-time fee of $49.95 if approved,” Jennifer wrote in a review posted on ConsumerAffairs.

“My credit has improved and all my cards have just given me an increase. I will be paying off and canceling this card right away.”

Overdraft fees. The head of the CFPB earlier this year called overdraft fees “a massive junk fee harvesting machine.” JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo have been especially charge-happy, accounting for about one-half of overdraft revenue reported by big banks in 2022.

The agency has proposed closing the loopholes that allowed banks to feast on $30 to $35 overdraft penalties. For years consumers have been especially aggrieved by how a series of debit card purchases on a single shopping trip will rack up multiple $32 fees before they learn that they have overdrawn their accounts. A bank’s cost of covering the temporary deficit can be as low as $3.

Sometimes consumers do nothing wrong and still get charged. Sara, of Burnsville, Minnesota, claimed that U.S. Bank held a cashier’s check for eight days, causing her account to go negative.

“[I was] charged overdraft fees, and then [they] said, ‘Sorry there is nothing we can do, have a nice day,'” Sara wrote in her review. “There is no reason to hold up a certified cashier’s check, NONE.”

Consumers who use payday, car title or pawnshop loans also seem increasingly prone to nonsufficient funds (NSF) fees. The CFPB reports that these borrowers are also hit with fees for “rollovers,” extended repayment plans and when loans are loaded onto prepaid debit cards.

Bank fees. Large banks charge fees if balances fall below a certain level. They also can charge account maintenance fees, fees for not having a certain number of monthly transactions, fees for making too few direct deposits and fees for making transfers or transactions.

“Some of these fees may be things you’d never think to ask about,” McLaughlin said. “So it’s always a good idea to take a close look at both the terms and conditions as well as your account charges so you know if any of these fees are eating away at your savings.”

Swipe fees. Craig Shearman, a spokesman for the Merchants Payments Coalition, which lobbies for payment system reforms, says swipe fees are most merchants’ highest cost after labor and drive up prices by over $1,000 a year for the average family, adding to inflation. That’s because while consumers don’t pay these fees directly, the merchants, gas stations and restaurants that do pay them are simply passing them along to consumers, often adding 3% to a charge.

“The answer for saving on swipe fees is for Congress to pass legislation to make banks and card networks compete over these fees the same as other businesses compete over pricing, quality and service every day,” Shearman said.

Reformers versus the opposition

In early March, the CFPB finalized a rule that limits credit card late fees to $8, the estimated actual cost to banks to cover the shortfall.

While the CFPB’s proposed rule suggests hope for fee-weary consumers, banks and credit card companies aren’t giving up without a fight. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce said it will sue CFPB to block the rule’s implementation. Chamber Executive Vice President Neil Bradley said that for most consumers the new rule would drive up credit costs and tighten credit.

The rule, Bradley said, “punishes Americans who pay their credit card bills on time by forcing them to pay for those who don’t. This will result in fewer card offerings and limit access to affordable credit for many consumers.”

Bradley also said the CFPB has exceeded its legal authority in proposing the rule. Left unsaid is the impact the new rule would have on big banks’ stock prices. A reduction in revenue from fees could reduce profit margins, causing big bank stock prices to fall. Wall Street has an interest in maintaining the status quo.

Mansfield, the law professor at Case Western Reserve, wouldn’t venture a guess as to whether banks will be able to block the proposed rule from taking effect, but she said she is encouraged by the attention the issue is receiving.

“Junk fees are certainly a big issue for the Biden administration, as it should be,” she said.

She believes the issue with bank fees of all types is one of transparency, noting that the European Union has stronger rules requiring companies to announce the size of fees to be charged in advance so consumers aren’t surprised by seemingly fluid fee decisions. “If the price you saw was actually the price you’re going to pay, you could make more informed decisions,” she said.

Mansfield said her big concern is that caps on overdraft fees and credit card late fees could lead to more and higher fees elsewhere. For example, instead of covering the overdraft and charging the consumer $8, the bank could simply bounce the check and charge a bounced check fee, something she said regulators need to consider.

In the meantime, if banks can’t make a profit on credit card or overdraft fees, Mansfield says they’ll explore other avenues. “Will they continue to make money off of us?” she asked. “No question.”

In the meantime, what can consumers do?

Consumers can vote with their feet, says Gabe Krajicek, CEO of Kasasa, which operates a small bank rewards program. Big bank customers should consider the savings if they move their accounts to a smaller community bank.

“Because of their size, structure, and local focus, they have less overhead and can offer lower fees and higher returns than megabanks,” he said. “Now is a great time to search. There are community banks and credit unions that offer accounts with no minimum balance requirements to earn rewards, no monthly maintenance fees, nationwide ATM fee refunds, and free high-yield checking accounts — many greater than 5%.”

Kasasa-affiliated banks also refund out-of-network ATM fees if the depositor makes a certain number of monthly debit card transactions, another reason consumers might consider switching to a smaller bank.

McLaughlin says some consumers mistakenly believe their money is safer in one of the major, “too-big-to-fail” banks, pointing out that the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) covers all banks, large and small.

“No consumer has ever lost money in a federally insured account, as long as they abide by the guidelines,” he said.

Another thing that consumers can do is complain: The analysis of CFPB data shows that 26% of people who complained to their bank or credit card issuer got a resolution in the form of money back.

In the age of social media, banks would like to contain customer dissatisfaction. A refund is a small price to pay to head off a potential viral post.

This story was produced by ConsumerAffairs and reviewed and distributed by Stacker Media.