The jean evolution: How denim styles have reflected America over the past 120 years

Photo Illustration by Elizabeth Ciano // Stacker // Warner Brothers/Getty Images

The jean evolution: How denim styles have reflected America over the past 120 years

A photo illustrations depicting James Dean wearing jeans against a backdrop of the American flag.

Few things connect world citizens like food, music, and vanity. Everyone—no matter the context—wants to look good. With an article of clothing as common as denim jeans, it’s easy to underappreciate how it has cut across time and society toward universal acceptance.

Once a symbol of the “unwashed” masses, jeans have become the unofficial uniform of modern society. In just over 50 years, denim’s contemporary trajectory and history have taken us from Europe’s Mediterranean coast to the newly established world of the United States to the “bad boys” of 1950s Hollywood through to New York’s many boroughs during the 1970s and ’80s and, most likely, into your own closet.

The global history of the jean is a story about invention and commerce, fashion, changing societal norms, and how we collectively choose to adorn ourselves for each other.

To more fully explore this now-classic and infinitely flexible fashion item, Stacker retraced the history of denim—a pant that has shaken societies and made vast fortunes—on its journey to become the world’s favorite piece of clothing, using various sources, including Vogue, National Geographic, PBS, and Levi Strauss & Co.

You may also like: 25 idioms that were common in the ’70s

![]()

ullstein bild via Getty Images

The 17th-19th century: Serge de Nimes

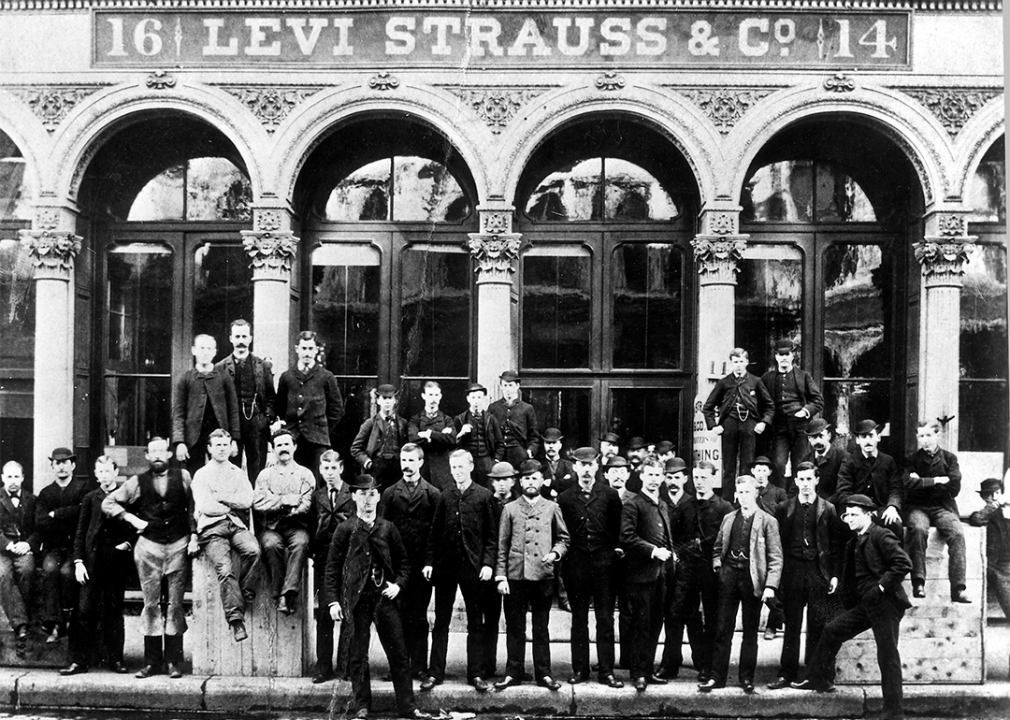

Exterior Levi Strauss & Co Factory in San Francisco.

Denim is arguably seen as an American institution due to its origins in the rugged, dusty times of the California gold rush. The fabric, with its distinctive blue and white weave, is actually a French creation, originating from the city of Nîmes, a former Roman colony in the Occitanie region of southern France.

In the 17th century, French textile makers called this strong fabric, which was then made of wool and silk, “serge de Nîmes,” or “a sturdy fabric from Nîmes.” The name eventually gave rise to the word “denim.”

By the 18th century, this early predecessor to denim had crossed the channel to England. But the British made their own alterations, dropping the precious French-milled wool and silk and creating a new cotton variation more durable and resistant to the thrashings of a worker’s life.

By 1789, the fabric had made its way to the shores of the United States, first documented in Massachusetts. Another early acknowledgment of the fabric’s presence in America was recorded in John Hargrove’s 1792 book “Weavers Draft Book and Clothiers Assistant,” which contained technical sketches of how to weave and produce denim.

Some 60 years later, in 1853, the German immigrant Levi Strauss, (the “Levi” in Levi’s jeans), would start a company supplying dry goods, including cutting overalls for workers of America’s developing West. It wasn’t until 1873 that the modern jean would be invented, when Strauss and a Nevada-based tailor, Jacob W. Davis, added copper rivets to the pockets.

George Rinhart/Corbis via Getty Images

The 1950s: Denim as fashion

James Dean and Elizabeth Taylor in a publicity photo for “Giant.”

Between Strauss’ workings and the 1920s, denim was regarded as a purely utilitarian fabric, a symbol of hard work and dirty graft, and not an article of fashion. By 1890, Strauss and Davis’ patent had expired, allowing competing companies such as OshKosh B’gosh, Wrangler, and Lee into the market. In fact, Lee Union-All jeans became de rigueur for war workers.

This would change due to the rise of Hollywood, particularly in the 1950s. The influence of the silver screen would give the jean its close-up. For men, it was portrayed as a garment for countercultural “bad boys” typified by actors like James Dean and Marlon Brando, who wore them, boot-cut-style, with a deep cuff, and paired with slick, black leather jackets. For the women, the look was form-fitting, stopping at various lengths above the ankle.

Hollywood’s command over U.S. culture meant the country’s youth would be heavily influenced, thus making the jean a mainstay in the average American’s wardrobe.

Wally McNamee/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

The 1960s: The rights of Americans and denim

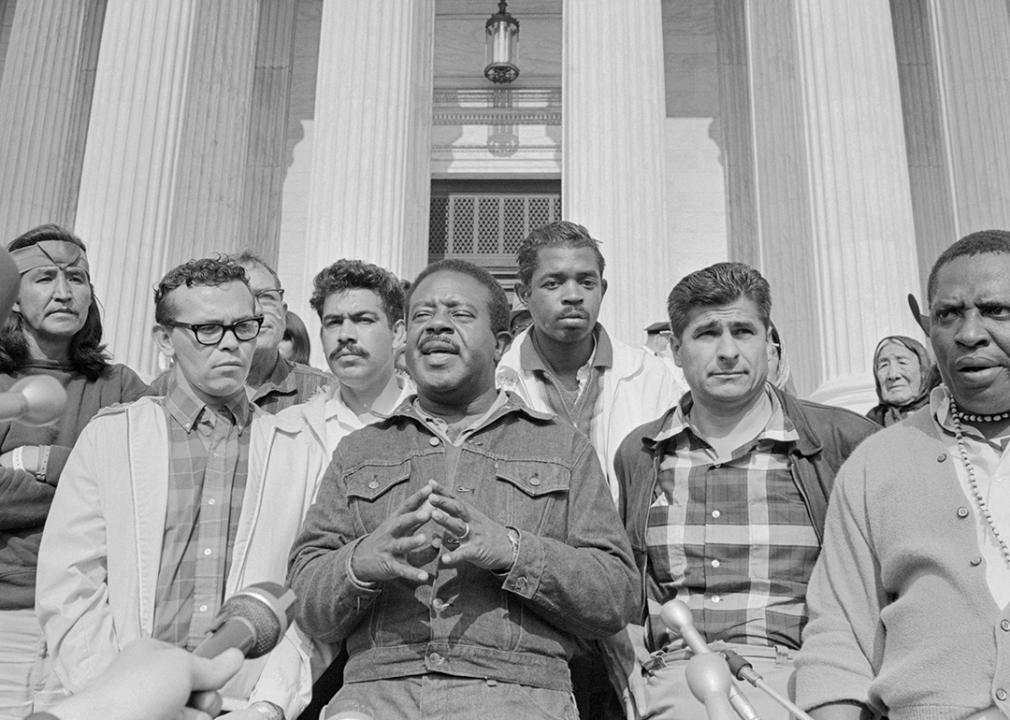

Ralph Abernathy with supporters at The United States Supreme Court.

In the 1960s, because of its connection with the working-class man, the Civil Rights Movement adopted the denim jean. Activists would often sport rugged wear that could withstand hours of knocking on doors and canvassing rather than wear their Sunday best.

“Whether in trouser form, overalls or skirts, it not only recalled the work clothes worn by African Americans during slavery and as sharecroppers, but also suggested solidarity with contemporary blue-collar workers and even equality between the sexes, since men and women alike could wear it,” political writer Brandon Tensley wrote for Smithsonian Magazine.

Civil rights activists like Martin Luther King Jr. and Ralph Abernathy and young members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee would march to history wearing them.

Keystone Features // Getty Images

The 1970s: Denim meets high fashion

Model Vera von Lehndorff wearing a denim jacket and jeans.

Until the late 1960s, the power dynamic of high fashion was top-down. Usually, designers from their salons told the broader public what was fashionable. French designer Yves Saint Laurent broke that paradigm when he took inspiration from the Paris street riots and protests of 1968 and created a line of tailored trouser suits for women. This would gradually relax societal dress codes, only further fueled by Calvin Klein, a Bronx-born designer.

By the late 1970s in America, Klein gave his customers something familiar but special: denim, done the “designer” way. That meant jeans branded and cut to accentuate certain parts of the body. Showing denim on the runway in 1976 would be a historical event, making him the first designer to exhibit it on the catwalk.

In fashion speak, it was a moment, and denim was accepted among those in high design—even among the snooty echelons of European fashion.

Barbara Alper // Getty Images

The 1980s: Sex and jeans

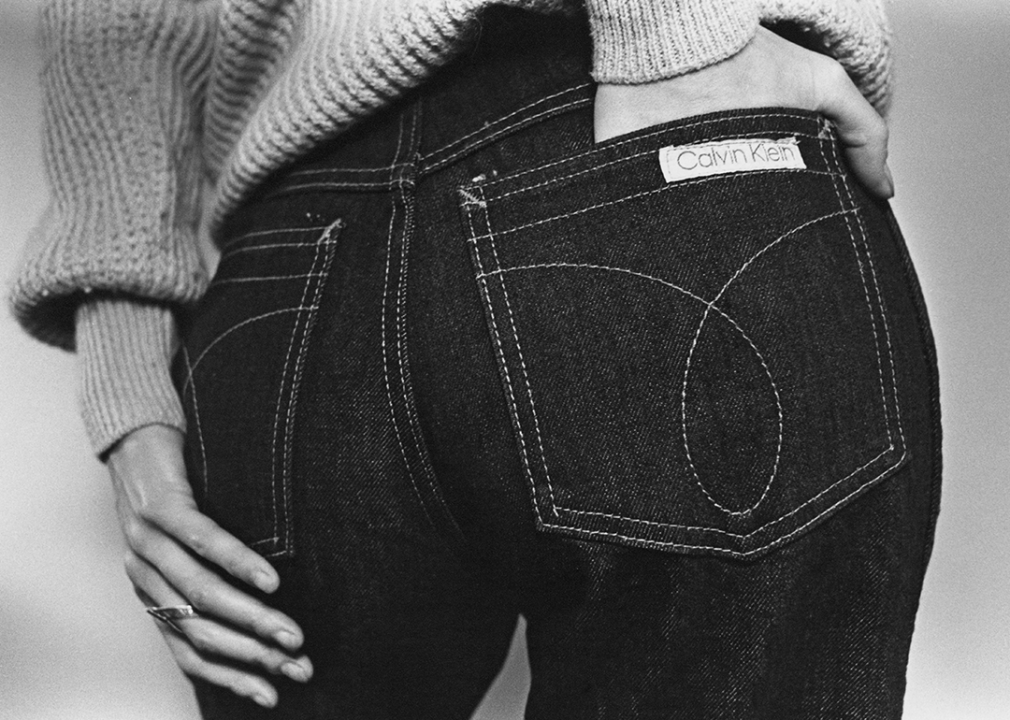

The back pocket of a pair of Calvin Klein jeans

After his leap of faith, Klein used jeans to seduce America’s wealthy. In the early 1980s, Klein (not yet considered legendary but an established designer) started employing provocative branding techniques—like displaying erotically charged billboard advertisements—to further sell his vision to the world.

“Of all the pictures that were taken it was the series of photos of Tom Hintnaus, a Brazilian-born Olympic pole-vaulter, that struck Klein as the images. Weber’s shots of Hintnaus arching his naked torso against a white wall in Calvin Klein underwear—his ‘package’ competing for its own gold medal—were chosen for billboards and bus-shelter posters,” Ingrid Sischy, the art critic and culture writer, once reminisced in her 2008 Vanity Fair profile of the designer.

Sischy added: “I was on a crosstown bus in Manhattan early one morning right after they’d been put up. When we passed a shelter almost everyone on my side of the bus swiveled his or her head to get a better look at the image, which was basically shoving the man’s physicality down the audience’s throat. I was so curious about it that I got off the bus so I could see it properly.”

Those images—including a then-15-year-old Brooke Shields staring into the camera and asking, “You want to know what comes between me and my Calvins?”—caused an uproar and thus made the Calvin Klein jean a pop culture star.

You may also like: The rise of ‘fast furniture’: What is it and what are sustainable, affordable alternatives?

John Aquino/David Turner/Penske Media via Getty Images

The 1990s: Denim and the (inner) city

Models dance at a Tommy Hilfiger collection presentation.

By the 1990s, hip-hop’s infiltration of the American mainstream had more than started. Birthed out of the burned-out ruins and urban strife of 1970s and ’80s New York City, hip-hop would embrace Tommy Hilfiger, whose style of accessible, Americana-inflected prep captured the upwardly mobile, aspirational yearning that undergirded the nascent cultural juggernaut.

Direct competitor Ralph Lauren fostered an aesthetic rooted in the very real, if heightened, interpretation of the New England White Anglo-Saxon Protestants. Lauren’s world—a universe referencing precisely clipped green lawns of Bedford, New York; Ivy League education; and generational wealth—could be intimidating if you didn’t already understand its particular cultural nuances. In contrast, Hilfiger’s designs were more democratic: baggy, brash, and less expensive but vibrant with the colors of the U.S. flag. The decade saw hip-hop mainstays like TLC, Mary J. Blige, and even Beyoncé rocking the red-white-and-blue logo and baggy fit.

The coupling of cool, urban, Black youth with Hilfiger’s upmarket clothes was unlikely but influential. Again, like the 1950s, America’s youth, from the inner cities to the homogenous suburbs, would follow, inspired by this new demographic mix, and with them, would move the country’s broader culture.

Evan Agostini // Getty Images

The 2000s: A change in proportion

Gisele Bundchen, Alessandra Ambrosio, Heidi Klum, Adriana Lima and Tyra Banks kick off the Victoria Secret Angels Across America tour.

Historically, the most important designers have somehow changed the proportion of the physical form. Coco Chanel did it with her Chanel suit, which changed the shoulder line and softened the silhouette of the female body while freeing up the legs.

In the 1990s, it was British designer Alexander McQueen who would start his meteoric career by introducing the “bumster” trouser, a transgressive new pant style whose waist was lowered from the natural positioning on the body down to the pubic bone to elongate a wearer’s legs. The change elongated the torso, giving the wearer’s body an intimidating edge, which was McQueen’s goal.

By the turn of the century, designers and brands from Paris runways to the malls of small-town America were selling a repackaged version of McQueen’s look, rebranded as “low-rise.” In contemporary fashion, it was a reversal of a woman’s erogenous zones, where usually the cleavage of the breast is highlighted. This time, the attention was behind the wearer, focused on a new cleavage: the buttocks.

Just before the digital age put a camera in almost everyone’s hands—paparazzi culture reigned supreme, fueled by a 24-hour news cycle via cable, and the internet increased global interconnectedness. The low-rise, seen on celebrities of the aughts like Britney Spears and Paris Hilton, was confirmed as the silhouette of the decade.

Most interpreted the lowering of the waistline as a signal of overt sexiness, a way to show one’s toned body, but what was mistaken as an invention for the male gaze was actually a design inspired by the gruff, “plumber’s cracks” of working-class East London, where McQueen had grown up.

Bauer-Griffin // GC Images

The 2010s: The vice grip of the skinny pant

Kendall Jenner, Gigi Hadid and Anwar Hadid shopping in Los Angeles.

American beauty standards for women primarily favored thinness, long flowing hair, and ample breasts. It was a criteria of desirability based on European standards, but starting in the early aughts through the 2010s, a sizeable rear end—rooted in a colonial “a fantasy of African hypersexuality,” as Heather Radke, author of “Butts: A Backstory” called it—would supplant the upper torso as the new celebrated body part.

Once broadly overlooked, certain influential women with curvy physiques came into vogue. Figures like Kim Kardashian, Beyoncé, Shakira, and Jennifer Lopez were considered the new standard bearers of beauty. In the past, this was held by women like the slightly built Audrey Hepburn, on one side of the spectrum, or the buxom vixeness of Pamela Anderson, on the other.

By the 2010s, America was witnessing the rise of athleisure (mostly women’s upmarket athletic wear) as education about health and well-being became societally more abundant and important. Suddenly, “workout attire,” formerly only for places like the gym, was accepted as a form of public day dress.

American society had completed the cycle, from Botticelli’s Venus to Ashley Graham, the West seemed to have found itself back at the beginning, celebrating a more voluptuous female figure. To show off generous behinds required tight-fitting pants that outlined the lower half of the form. The answer? The skinny jean, commonly made with a stretchy material, allowed the wearer some freedom in sizing and gave the wearer more options to determine how snug a fit they wanted against their own body.

Whether it be skinny jeans or athletic wear, idolizing this version of the female (and male) behind would be one of the most significant fashion shifts for decades.

Jacopo Raule // Getty Images

The 2020s: Denim 2.0

Kaia Gerber walks the runway during the Valentino Haute Couture Show.

For about 15 years, skinny jeans held a vice grip on a fashionable pant silhouette. Millennials, who had been influenced by the trend, were getting older, and Generation Z, finding their own identity through dress, preferred a baggier shape, reminiscent of the pant styles of the 1990s.

The second decade of the 2000s has been turbulent—lost to large-scale economic movements, pandemics, topsy-turvy geopolitics, the hollowing of America’s middle class, and the transference of unseen wealth to the top 1% of society. All the while, fashion, which has always been a snapshot of society, has reflected this reality.

Much like its runway debut in the 1970s, jeans in the 2020s have been given an expensive couture remix. Leather pants are printed on the surface to look like common denim, such as Bottega Veneta’s version, which goes for $7,000. Or they could be completely embroidered with tiny hand-stitched beads colored in variations of blue to mimic the look and texture of a regular pair of Levi’s. Valentino’s version led New York Times fashion critic Vanessa Friedman to wonder, “Are these the most expensive jeans in the world?”

These new interpretations are all about catering to the world’s überwealthy, providing them a way to showcase their wealth discreetly using a trick of the eye and materials traditionally associated with the everyday.

It’s a novel approach designers have taken to adapt to the times—until the next societal push changes everything once more.

Story editing by Carren Jao. Copy editing by Paris Close.