Commonly used phrases with hidden meanings

fizkes // Shutterstock

Commonly used phrases with hidden meanings

Woman looking at laptop thinking.

“You can’t step into the same river twice.”

This idiom is attributed to the late philosopher Heraclitus, who believed the concept of flux governs life. Nothing stays the same—people, environments, habits, or age. How we perceive things within our society and the processes we adopt constantly evolve, much like us, and include the words, phrases, and overall language we use.

There may not be an exact moment in history that pinpoints the birth of language, but scientists have attempted to narrow down the most accurate time frame. For quite some time, researchers concluded humans had spoken for at least 200 hundred thousand years. That is until a 2019 study suggested the “dawn of speech” could be traced back roughly 20 million years.

Each generation passes language to the next through man’s oldest form of cultural communication: storytelling. Long before the printing press or social media, storytellers carried our descendants’ lessons, histories, and cultural mores. These stories act as bookmarks along the timeline of our journey as humans, spotlighting the mindset of the people and prejudices that preceded us.

How did language first come about, and how did it form into the complicated syntax, grammar, and sentence structure it has today? That is a topic that would take far longer to parse through.

Instead, Stacker looked at how some commonly used phrases and idioms came about in America. While most evolve from innocuous origins, others are born from a place with undertones that are far darker, more nefarious places.

Continue reading to discover if these 25 commonly used phrases with hidden meanings remain in your vocabulary.

![]()

Brian A Jackson // Shutterstock

Paying through the nose

Hundred dollar bills in a row.

There you sit, one hand holding a cell phone, the other floating above your laptop keyboard. Your eyes are open as you stare at the countdown clock. The numbers flash zero, and those concert tickets you’ve been saving for are soon to be yours—and just as suddenly as you’re in the queue, they’ve sold out. Now the resale prices are triple the original price, and you think, “I’m paying through the nose for these seats!” as you max out your credit card.

In essence, it just means you’re being charged far more than the value of something. Though Dictionary and Grammarist disagree on its exact origins, they do agree there was once a practice in which someone would slit people’s noses from tip to top if they didn’t pay their taxes.

Michèle VIGNES/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

Drinking the Kool-Aid

Portrait of Jonestown cult leader Jim Jones.

The phrase “drinking the Kool-Aid” originated from a much more dangerous place than refined sugars.

On Nov. 18, 1978, more than 900 people, more than 200 among them children, took part in a mass suicide by drinking a cyanide-laced punch drink under the direct instruction of cult leader Jim Jones, who then shot himself in what is known as “The Jonestown Massacre.” This idiom was born from their deaths. However, they drank Flavor-Aid, not Kool-Aid.

Wilhelm Scharmannullstein bild via Getty Images

It’s a cakewalk

Historical image of a cakewalk performance.

As you may remember from your elementary school’s spring carnival, a cakewalk is a game where people form a circle and walk or dance to music until it stops. Whoever lands on the winner’s circle by the time the song ends wins a cake. The rules are simple, the game’s basis is chance, and it requires little effort to win, which explains why people started calling an easy victory “a cakewalk.”

The story behind the cakewalk dates back to slavery, in which plantation owners hosted these types of contests for those they enslaved. Later, people duplicated the dances born from cakewalks in minstrel shows.

Everett Collection // Shutterstock

Long time, no see

Man waving on bicycle.

The phrase, a simple way to say it’s been a long time since you’ve seen someone, first appeared in print in a Western written by William Drannan in 1900, in which Drannan uses the phrase as part of a dialogue with an Indigenous American. But a theory that contradicts that origin claim says it comes from the pidgin English Chinese people used when encountering the British Royal Navy. Either origin points to the phrase being born through the mockery of people of color.

Canva

Riding/calling shotgun

Historic photo stagecoach.

Friends, family members, and carpoolers have all fought for the illustrious title of “shotgun!”—meaning you’re riding up front on the passenger side. The one riding shotgun is the navigator of the voyage, if you will. Riding shotgun during the times of stagecoaches, however, meant you were responsible for holding the gun during the journey, and it was your job to defend against robbers.

Hans Henschke/ullstein bild via Getty Images

Eenie meenie minie mo

Children playing game in a schoolyard.

As children, when it came to choosing team captains or who was up to the plate first at kickball, one of the easiest solutions was to play “Eenie meenie minie mo,” a simple rhyming game in which whoever was still singing at the end of the song pointed at someone, naming them “it.” However, the lyrics we remember as children are not the original. While the children’s rhyme had us all trying to catch a tiger by the toe, the original words were overtly racist and utilized a slur instead of “tiger.”

Everett Collection // Shutterstock

The peanut gallery

Vintage theater.

Anyone with a quick wit and an even faster mouth has likely heard someone tell them, “that’s enough from the peanut gallery.” The phrase refers to the house’s cheapest seats, reserved for the hecklers. The elder Muppets, with their judgemental scowls, guffawing over everything and anything, are sat in the peanut gallery.

Before movies, television, and social media, there was vaudeville. Performers took to the stage in front of a live audience and entertained the crowd with jokes, gaffs, dance, and more. However, at the time of vaudeville, the section wasn’t reserved for critics or hecklers—it was where the theater forced Black people to sit.

Transcendental Graphics // Getty Images

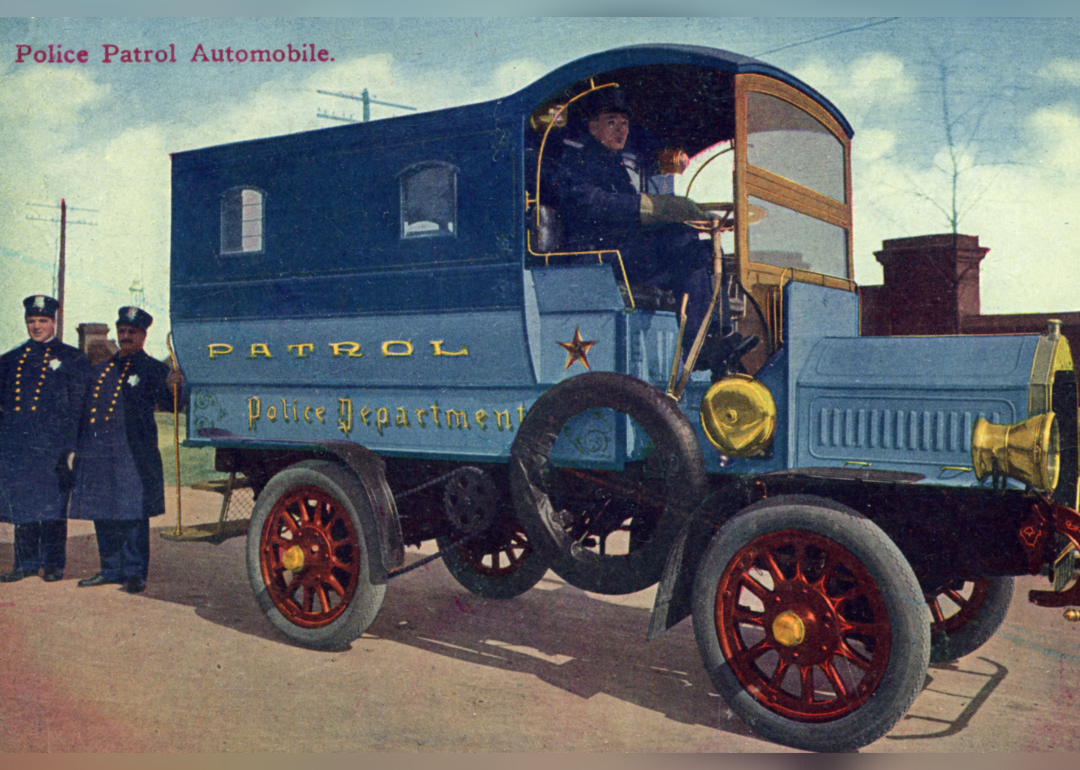

The paddy wagon

Lithographic postcard showing policemen in and around their patrol wagon.

“The paddy wagon” refers to the large van or police vehicle sent to pick up large crowds. In more recent years, police have used them as a way to corral and arrest protesters. The origin of the paddy wagon harkens to a time when Irish immigrants were making moves in droves to America. A “paddy” was a derogatory term for Irishmen, who people stereotyped as being always drunk and often violent.

rafastockbr // Shutterstock

Gimme the Jimmies

Spoon with chocolate sprinkles.

The Jimmies are more of an East Coast thing, but as a kid, if you were hitting the ice cream shop and you wanted chocolate sprinkles, you didn’t ask for chocolate sprinkles—you asked for the Jimmies.

One origin theory is that the name comes from James Bartholomew, who ran the first sprinkle machine. Other stories point to the term being a subtle allusion to Jim Crow and segregation: The sprinkles were brown, unlike the typical rainbow assortment, and were often left out.

Canva

Basketcase

Group of large baskets.

Calling someone a basketcase generally refers to the idea that someone’s brain is a mess they can’t keep straight. While that’s what the phrase means now, it meant something different in WWI, when it originated. First mentioned in 1919 as a citation in the Oxford Dictionary, a “basket case” was rumored to be a term assigned to the bodies of soldiers in such bad shape the government sent them home to their families in baskets.

Photo 12/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

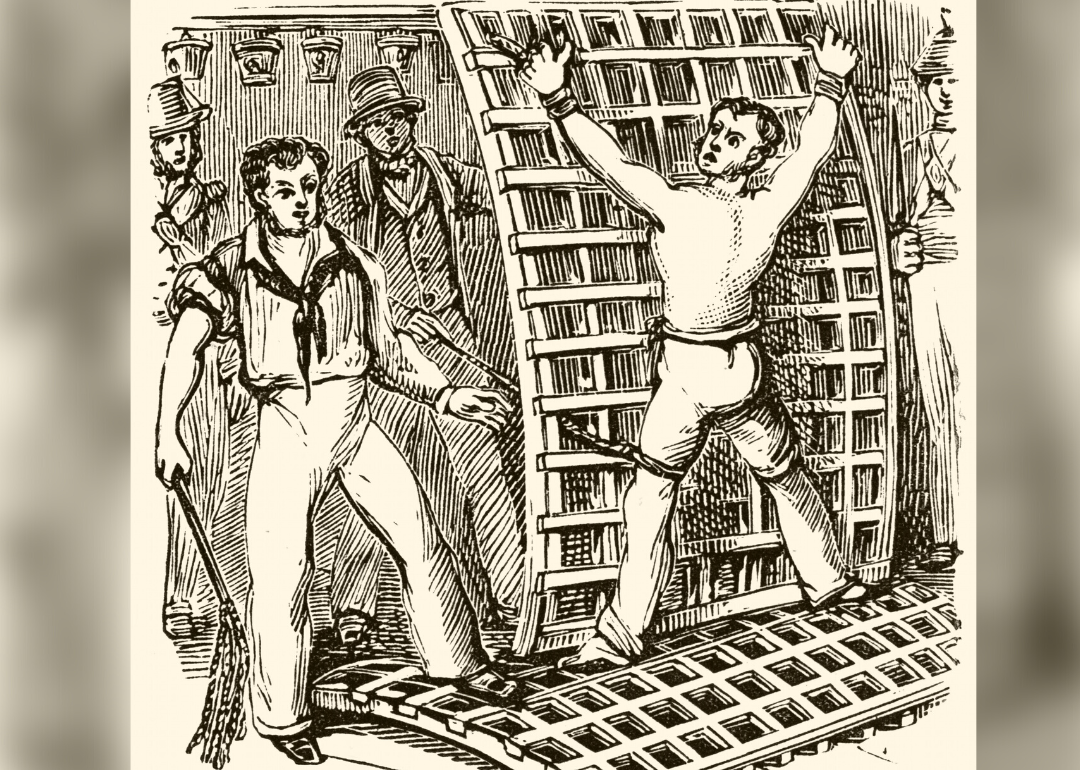

Cat got your tongue?

Illustration of British sailor being punished.

“Cat got your tongue?” is one of those snarky things you say to someone after you’ve insulted them so successfully they can’t come up with a retort. The origin traces back to the English Navy, who, as a punishment, would employ a cat-o’-nine-tails flogging device and beat the wrongdoers into submission or silence.

Everett Collection // Shutterstock

Sold down the river

Riverboats on the Mississippi.

When someone “sells you down the river,” it’s an act of pure betrayal. During the times of slavery, the Mississippi River was considered a major throughway for the enslaved to be shipped down the river and sold to various plantations throughout the South.

Canva

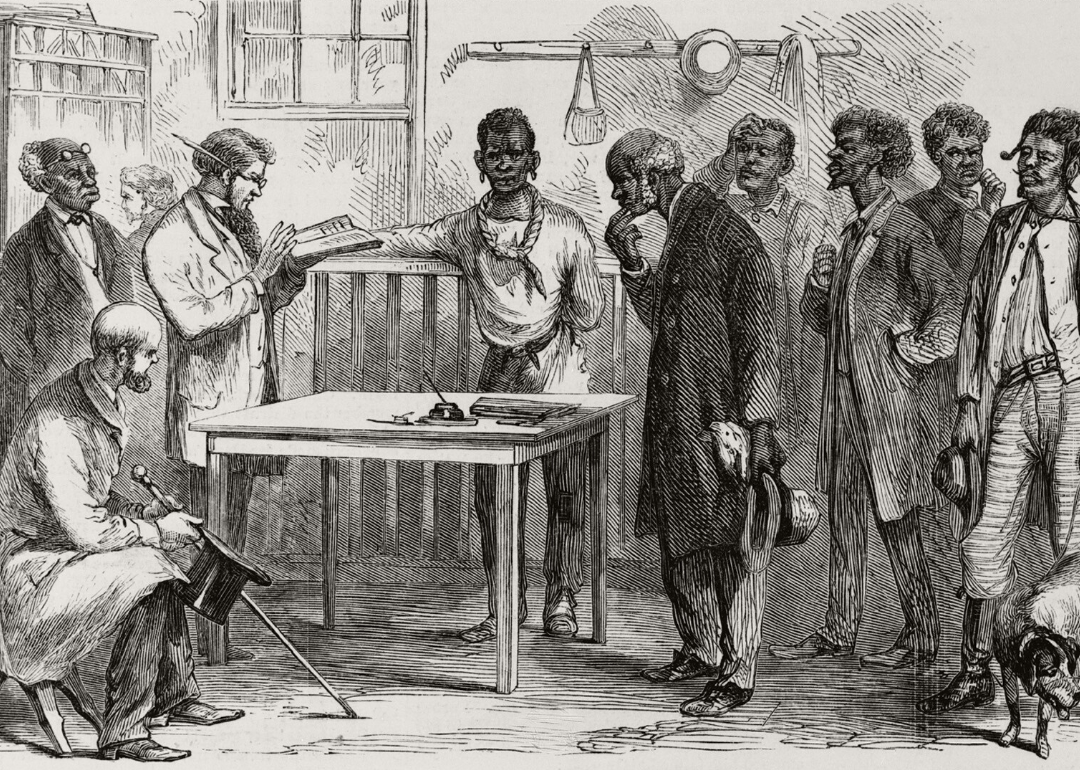

Grandfathered in

Illustration of freedmen at a voter registration office in Georgia.

When being “grandfathered in,” new rules established don’t apply to you because you were there before those rules were instituted. For example, if your bank sets new fees, but you are grandfathered in, you won’t have to pay.

The term comes from legislation passed by some Southern states that enacted new requirements necessary for people to register to vote—specifically recently freed Black people. The Grandfather Clause forced literacy tests and payments of poll taxes, among others, creating a Catch-22 situation for those who attempted to register.

Everett Collection // Shutterstock

Being moronic

Immigrants arriving at Ellis Island.

Psychologist Henry H. Goddard is known as one of the pioneers of eugenics, a science rooted in racism. Goddard claimed he could create a “more desirable” human population by weeding out the traits that made someone unworthy of reproduction in the eyes of eugenics.

Goddard is responsible for coining the term “moron,” which he indicated as a “feeble-minded person”—an argument that gained him and his team access to the immigrants attempting to enter America through Ellis Island. Through his work, nearly 40% of immigrants of Jewish, Italian, or Hungarian descent were deported or denied access to the U.S. by way of their “moronic” classification.

Corbis via Getty Images

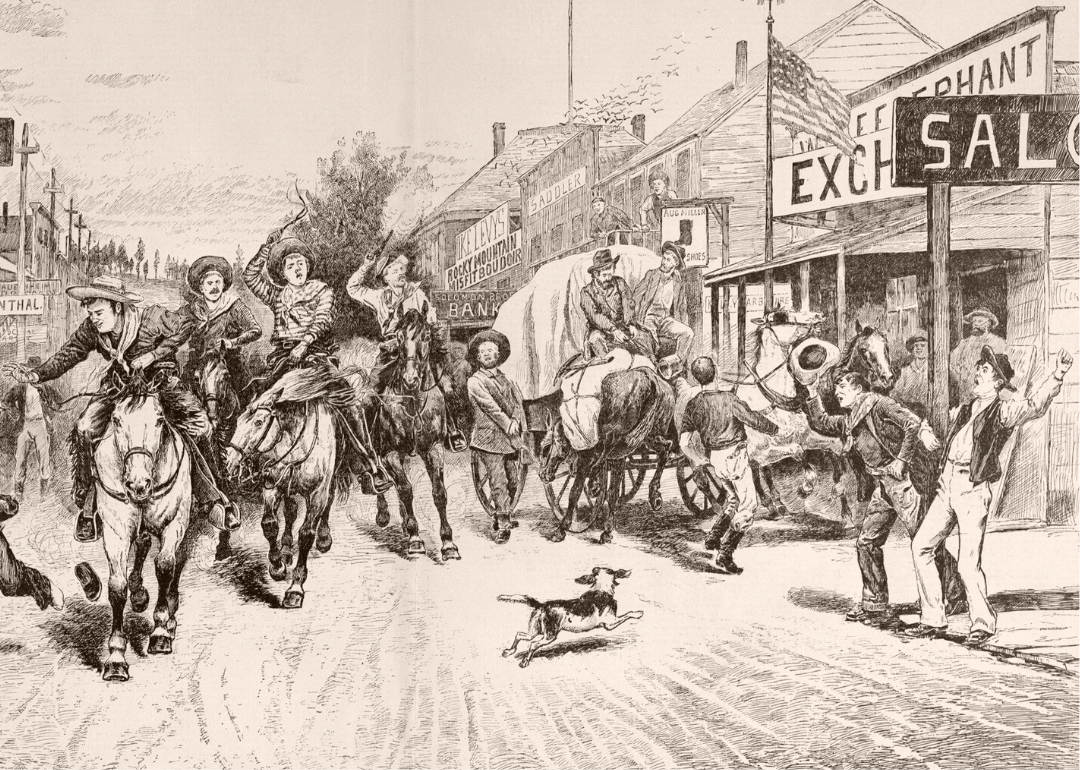

Painting the town red

Drawing by F.F. Zogbaum from 1886 titled Painting the town red.

To “paint the town red” is going out, having an amazing time, and possibly doing some things you may regret—or forget—by the morning.

Henry de La Poer Beresford, the third Marquess of Waterford, was a nobleman from the small town of Melton Mowbray and was known as a rabble-rouser in his day. Known as “The Mad Marquess” to the public, he was well known for fighting, breaking windows, stealing despite in no way needing to financially, and being politely but firmly asked to leave Oxford University. Legend has it that on one particular night, the Mad Marquis and a group of his friends went out and had a destructive night that ended in them finding cans of red paint and painting the town red.

Everett Collection // Shutterstock

You’re being hysterical

Vintage theatrical image woman with hand on head.

More than one woman has been called hysterical in her lifetime, but what does that mean, and where does it come from? Oxford Languages defines hysteria as an “exaggerated or uncontrollable emotion or excitement.” Where it gets a little tricky is hysteria’s etymology and the way it weaponizes mental health against women.

The term was coined in 1801 in medical Latin to describe a neurotic state believed to be associated with a dysfunctional uterus. The entire premise of the phrase is connected to an inability to control your emotions because you’re a woman.

Universal History Archive/Getty Images

Don’t miss your deadline

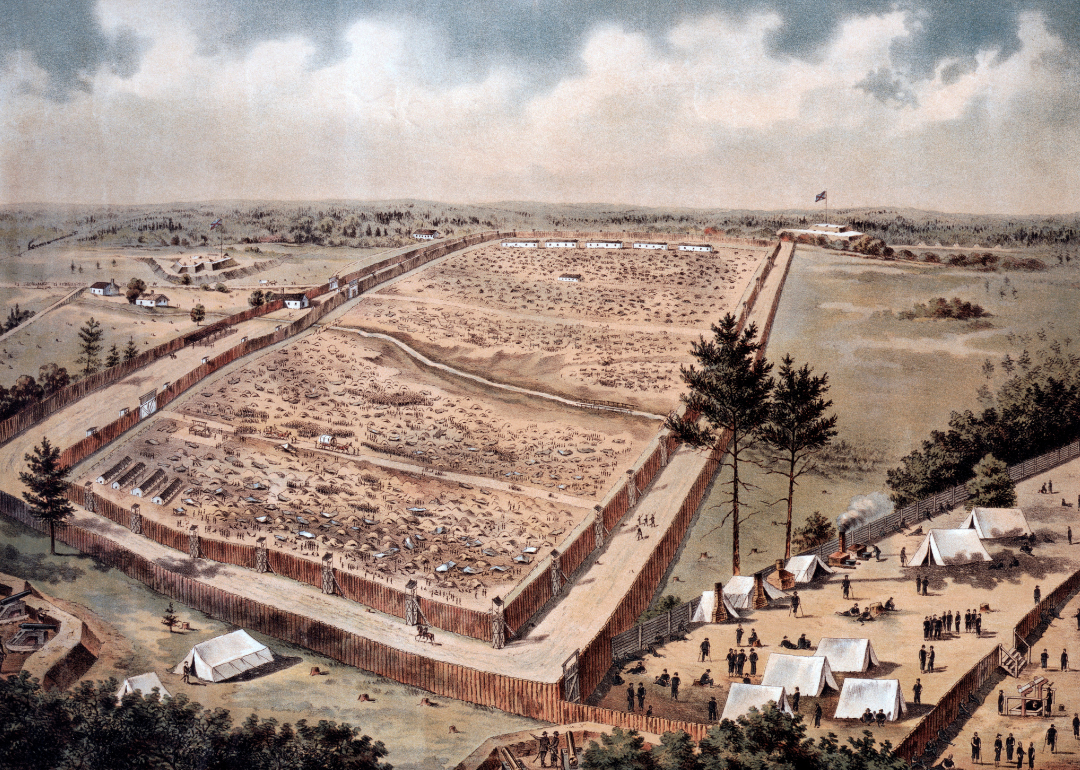

Illustration of Andersonville prison.

The word “deadline” strikes fear into procrastinators’ hearts. A deadline is a due date on which something needs to be ready, turned in, finished, etc. A teacher or editor isn’t to blame for this one, though.

During the Civil War’s bloody battles fought across stolen land, the Confederate soldiers would hold Union soldiers hostage, a typical war tactic. The Confederates erected crude fences around the small, cramped area where they held the Northern POWs. The “dead line” referred to the promise of immediate death to anyone who attempted to escape by crossing it.

Russell Lee/Library Of Congress // Getty Images

The tipping point

Man drinking at a segregated fountain.

While the definition of the “tipping point” calls it the critical point in a situation, process, or system beyond which a significant and often unstoppable effect takes place, the TLDR version just means you’ve reached your limit.

The concept of the tipping point began where segregation ended, and acted as a precursor to what became known as “white flight.” During the ’50s and ’60s, the phrase came into general practice when it was used to describe the point at which white families began to flee their neighborhoods because there were too many Black families moving in.

To quote a Pittsburgh Courier article from Feb. 10, 1962:

“He [a potential new neighbor] was told that he was welcome in Village Creek but not on Split Rock Road because his moving there would upset the delicate racial balance since [redacted] occupancy had already reached the tipping point which might turn Split Rock Road into a ‘ghetto.'”

Interim Archives/Getty Images

Hooligans

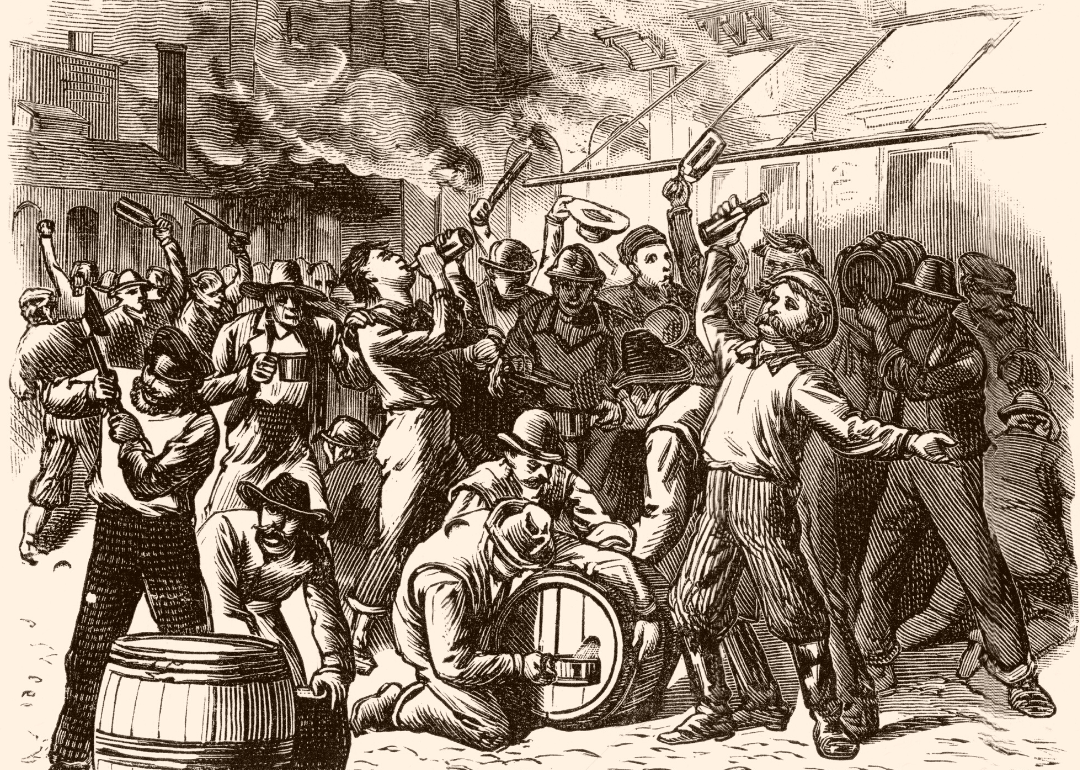

An illustration of rioters distributing stolen whisky.

The term hooligans is associated with soccer fans in the U.K., but long before the rowdy and raucous crowds took to the pitch, a cartoon of Irish immigrants took to the printers.

Drawn by T.S. Baker, the cartoon, also called “The Hooligans,” depicted Irish immigrants as lazy, oafish drunkards you could barely understand because of their accents—and then offered the proper Englishmen as a contrast. It was a form of propaganda intended to affirm stereotypes and instill prejudice against Irish immigrants.

Hulton Archive // Getty Images

Fuzzy Wuzzy was a bear

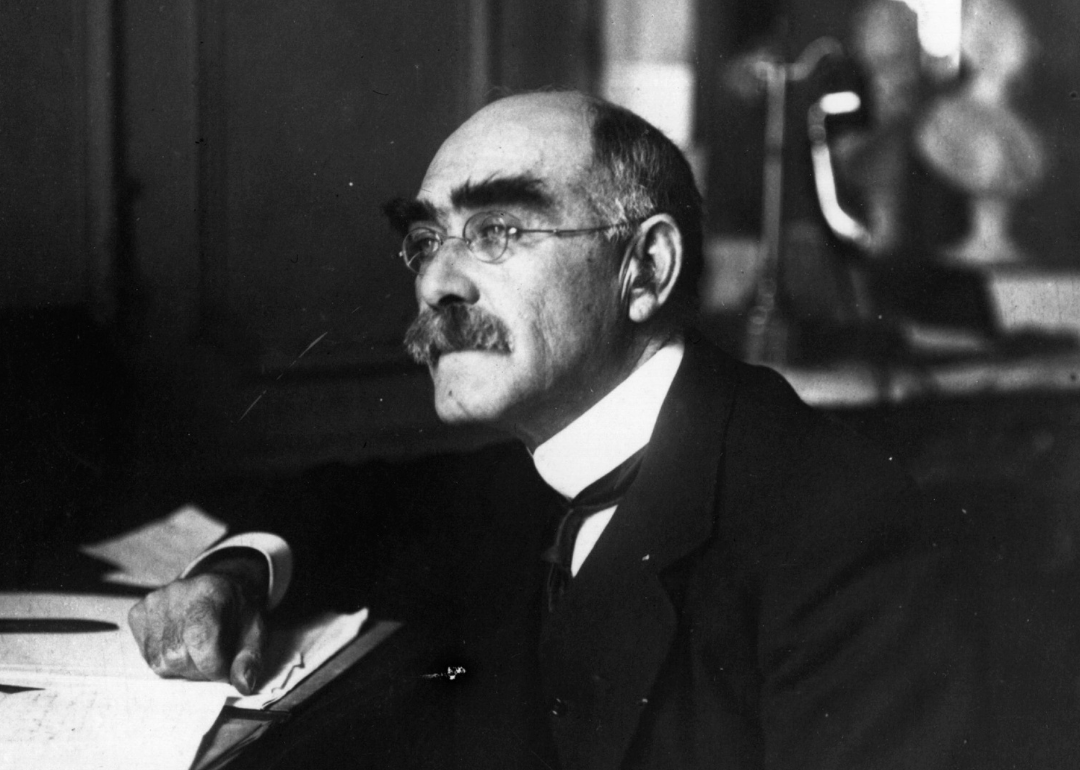

Portrait of Rudyard Kipling.

Another children’s rhyme from nefarious beginnings: “Fuzzy Wuzzy was a bear, Fuzzy Wuzzy had no hair, now Fuzzy Wuzzy wasn’t fuzzy, was he?” When you hear it, there’s nothing ugly about it. It feels sweet, cuddly, and warm, like the adorable teddy bear the rhyme speaks of.

The 1892 poem by Rudyard Kipling entitled “Fuzzy Wuzzy” waxed poetic on the brave soldiers who fought in Colonial Sudan. Throughout his gushing over the British, Kipling uses the term “fuzzy wuzzy” to describe the texture of the hair of the African tribes the British were attempting to decimate.

Everett Collection // Shutterstock

Off the reservation

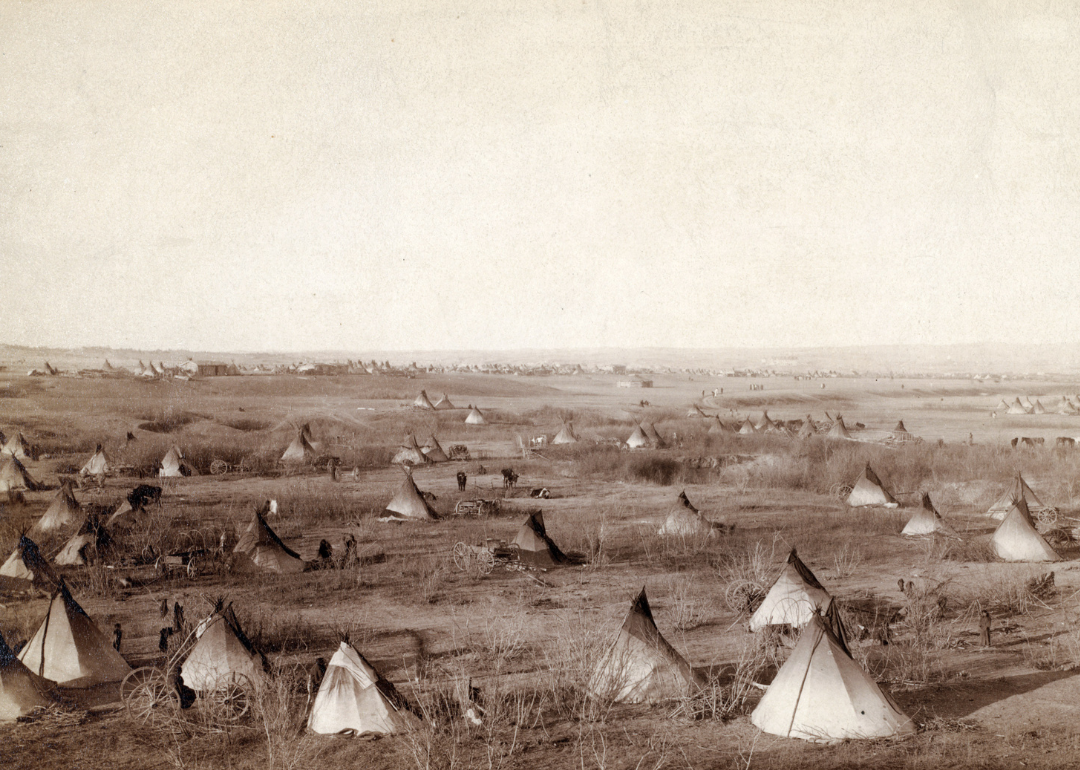

Historic photo of Pine Ridge Reservation.

Over time, “off the reservation” grew to mean someone who had diverted from their party or politics. The phrase in the 19th and 20th centuries referred to politicians diverting too far to the left or right of their established belief system.

However, the term traces back to when the United States forced Indigenous Americans into land treaties and moved them onto “reservations”—swaths of nearly uninhabitable land—after stealing their homes stolen and destroying their culture. It became a common expression to describe any movements Indigenous Americans made off the reservation.

Canva

Gypped

A wagon.

This racial slur managed to bore its way deep enough into the general vocabulary that most people may only know it as a term that means getting cheated, robbed, or swindled. However, the spelling of the word may offer some indication as to where the issue derives.

“Gypped” is a form of the word “gypsy,” a derogatory term aimed at the nomadic tribes of the Romani people, or the Roma, who migrated from Northern India to Europe. It is steeped in a Western stereotype that implies nomadic tribes are thieves.

Morphart Creation // Shutterstock

Bugger

Vintage engraving depicting the heretics of Orleans march to death.

If you’ve happened to see, well, nearly any British movie in the last 20 years, you more than likely have heard the phrase “bugger off” uttered. Today, “bugger” means a mischievous person or a snarky way to tell someone to get away from you.

The historical development of the phrase comes from something a little less impish, though. The term is thought to have come from an Old French word: the 14th-century “bougre.” The word referred to either a heretic or sodomite, depending on the context.

Rawpixel.com // Shutterstock

The itis

People seated around Thanksgiving table.

The technical term for “the itis” is “postprandial somnolence.” Having “the itis” typically refers to someone about to slip gently into a long food nap. It means feeling lethargic, lazy, and too full to move. Maybe you unbutton your jeans a little. Maybe you change into sweatpants. Either way, “the itis” got you. The seemingly innocent term is a shortened version of a highly offensive early 20th-century racial slur.

Vitalii Vodolazskyi // Shutterstock

Spaz

Diagnosis listed as spasticity on medical form.

Long before Pharrell was “Happy,” he was making music with N.E.R.D and, in 2008, released a single from their 2008 album “Seeing Sounds” entitled “Spaz.” The song was a loud, chaotic, eclectic mashing of sounds, and the chorus constantly told listeners to “spaz if you want to.” At the time, this slang had evolved to mean someone who didn’t have a care and would do what they wanted, when they wanted.

The word began as a derogatory term to describe someone clumsy, awkward, unaware of their body, or hyperactive. It was offensive because it originally came from the medical term “spasticity,” a condition that may affect a person’s speech patterns and can cause uncontrollable muscle spasms. It was shortened to “spastic” and shortened further to “spaz.”

Story editing by Jeffrey Smith. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.