Going to extremes: How Olympians vying for the gold in Paris contend with climate change

Photo illustration by Michael Flocker // Stacker // Shutterstock // Canva

Going to extremes: How Olympians vying for the gold in Paris contend with climate change

Five circular depictions of sport and climate against a backdrop of the Eiffel Tower.

Competition may not be the only thing heating up at the 2024 Olympics. Following scorching temperatures in Paris last summer, extreme weather patterns fueled by climate change may create more dangerous conditions for this year’s athletes.

Meteorologists can’t completely predict what Mother Nature has in store for Olympians. But last summer, Paris experienced above-average temperatures for nine straight days, and temperatures reached 95 degrees Fahrenheit in September. These extreme weather events have put new pressures on athletes at all levels, forcing them to pay more attention to how the heat affects their health and performance.

Stacker used data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and other meteorological organizations to explore the temperatures of past Olympic Games and what climate change means for the quadrennial event in years to come.

Rising temperatures have wreaked havoc on sporting events in recent years. Event organizers and sports federations have had to create new policies—or even cancel events, like the 2023 Twin Cities Marathon—to keep athletes safe. Heat and humidity can cause permanent physical harm and even death, particularly when physical exertion occurs during prolonged, sustained exposure to the elements.

France is no stranger to making heat-related accommodations for sporting events: The nation hosted the 2019 Women’s World Cup during a heat wave. In the quarterfinal match between the U.S. and France, players competed in 90-degree weather. FIFA, the international soccer governing body, implemented mandatory cooling breaks when temperatures reached 90 so players wouldn’t overheat. In 2022, FIFA instituted mandatory breaks at the 89-degree mark or higher, allowing players to hydrate and cool off in potentially dangerous heat.

Extreme heat did not spare France’s prestigious Tour de France. In 2022, France experienced three brutal heat waves that were directly responsible for over 2,800 deaths, making it the country’s deadliest summer since 2003. One of these heat waves occurred during the Tour de France. According to the Washington Post, the finish day was forecast to be 93 degrees Fahrenheit, 20 degrees beyond the July average high. High temperatures throughout the race forced organizers to spray down roads to prevent buckling and allow more hydration. Still, heatstroke sent one rider to the hospital.

A year later, temperatures spiked again: The 2023 race also had cyclists riding through heat waves that hit many areas of France.

Extreme temperatures have wrought havoc on sporting events around the globe. In Qatar, the nation’s bid to become a destination on the world sports stage took a disastrous turn due to the heat. Qatar is located in one of the fastest-warming areas on Earth. The nation’s annual mean surface air temperatures rose nearly 4 degrees Fahrenheit between 1922 and 2022, compared to an increase of about 2 degrees Fahrenheit worldwide since the early 1900s. Track and field events at the 2019 World Athletics Championships in Qatar’s capital took place in an air-conditioned stadium, but marathoners and race walkers competed on city streets in the desert heat.

Organizers shifted the women’s marathon start time to 11:59 p.m. in hopes of runners hitting their stride in cooler weather. However, the temperature was still a brutal 90 degrees Fahrenheit, contributing to 28 of the 68 runners dropping out, some of whom were carried away in stretchers. Thirty runners sought medical attention as a precaution. Unsurprisingly, researchers found the heat contributed to poorer performances, sharing their findings in a 2022 journal article.

After the race, a different sort of challenge took place. Some athletes expressed frustration with World Athletics, which allowed them to compete in high temperatures and brutal humidity. Belarus’ Volha Mazuronak, the fifth-place finisher, expressed her frustration to The Guardian: “The humidity kills you,” she said. “There is nothing to breathe. I thought I wouldn’t finish. It’s disrespect towards the athletes.”

As athletes contend with extreme temperatures, the heat is on for sports organizations

Climate change has affected sports for decades. “The Olympics and some of the bigger sport organizations started paying attention in the early ’90s, and this was largely linked to sustainability entering the public lexicon,” Madeline Orr, assistant professor of sport ecology at the University of Toronto, told Stacker. Sporting organizations began to shift their approaches to climate change.

While sporting organizations are making changes from the sidelines, athletes are experiencing the heat’s effect on their performance in real time. A 2023 World Athletics survey found that 3 in 4 track and field athletes felt that heat had a negative effect on their health and performance. Acknowledging athletes’ feedback, the International Olympic Committee developed a consensus statement to guide organizations on managing heat better.

The Winter and Summer Olympics, the pinnacle of sport, each occur once every four years. The Games have expanded over time to include more sports, athletes, venues, and spectators, driving up their carbon footprints. “That took off in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s with globalization and cheap passenger travel, and it became a tourism spectacle and a commercial spectacle,” Orr said.

Sports organizations and athletes face formidable challenges. While they can oversee some aspects of athletics in a changing climate, the mindset and ambition of individual elite athletes are beyond their control. An Olympic gold medal is the most coveted prize among athletes. It’s no exaggeration to say that Olympians give their all—and that makes it tough for athletes to admit when the heat has gotten the best of them.

“Being an athlete is about the art of pushing your limits just enough to get the most out of your body,” Sam Mattis, a 2020 Olympic discus thrower, told interviewers in a report published by the British Association for Sustainable Sport and Frontrunners. “When a variable like heat or wildfire smoke enters the equation, it throws off that balance and it can be hard to know where your limit is.”

You may also like: Inside the 2024 Summer Olympics: What to see, where to stay and more

![]()

Emma Rubin // Stacker

A history of sizzling Summer Games

Chart showing daily maximum temperatures throughout past olympics. Atlanta in 1996 reported the highest temperature. Both Seoul and Sydney held events in the fall to avoid heat.

Due to the Summer Olympics taking place during the hottest months for most host cities, organizers regularly have to factor heat into their planning. The exceptions are cities in the Southern Hemisphere, such as Sydney (2000 Olympics host) and Rio de Janeiro (2016 host), which welcome cooler temperatures during the Northern Hemisphere’s summer months.

During the 1992 Summer Olympics in Barcelona, heat and humidity took a toll on athletes, spectators, personnel, and animals. Temperatures reached the upper 80s even for evening events, like the women’s marathon. The winning time was nearly 8 seconds slower than the first women’s Olympic marathon in 1984. Horses also struggled in Barcelona’s climate, leading researchers to examine the effects of heat and humidity on horses.

A number of changes followed, and by the time Atlanta hosted in 1996, organizers moved start times to the morning, implemented mandatory breaks, and used rapid-cooling techniques on horses to prevent heat-related illnesses in the animals.

Summers in Tokyo are notoriously hot and humid, which made the Tokyo 2020 Olympics more difficult for athletes. “When you increase the moisture in the atmosphere, it takes more energy for your body to sweat,” Craig Ramseyer, assistant professor in the geography department at Virginia Tech, told Stacker. “It’s not as efficient, and you store that heat internally for longer.” Prolonged exposure to extreme heat and humidity can cause dehydration, fatigue, cramps, heat exhaustion, and even heatstroke, which can damage a body’s organs and even cause death.

During the Tokyo Games, 110 athletes suffered heat-related illnesses. The tennis matches were particularly brutal: Spain’s Paula Badosa retired from her quarterfinal match due to the heat, leaving the stadium in a wheelchair and covered in a cooling towel. Russian player Daniil Medvedev took medical timeouts in an early round match to cool down.

Organizers in Tokyo scrambled to make adjustments to create safer conditions for athletes, even relocating marathons and race walks more than 500 miles north to Sapporo in the hopes of cooler temperatures. Unfortunately, a heat wave in Sapporo meant race day temperatures weren’t much better than in Tokyo.

Even with the extreme conditions, Olympians pushed themselves to their limits. In testimony for the BASIS and Frontrunners report, New Zealand medalist Marcus Daniell said of the Tokyo games, “At the time I felt like the heat was bordering on true risk—the type of risk that could potentially be fatal. One of the best tennis players in the world [Medvedev] said he thought someone might die in Tokyo, and I don’t feel like that was much of an exaggeration, especially when you’re playing for your country and the desperation to perform is running through your veins.”

While lessons from Tokyo may inform the heat management approach in Paris, a different city brings new challenges.

In Paris, zinc-roofed buildings and limited public green space (just 10% of the city) create what researchers call an urban heat island. “There’s been an increase in moisture in the atmosphere and in Paris,” Ramseyer told Stacker. “And in places in Europe that get a lot of moisture out of the Mediterranean, for example, are not only warmer than they used to be, but much more humid than they used to be, and so that’s really concerning when you think about the Olympics being in Paris.”

Emma Rubin // Stacker

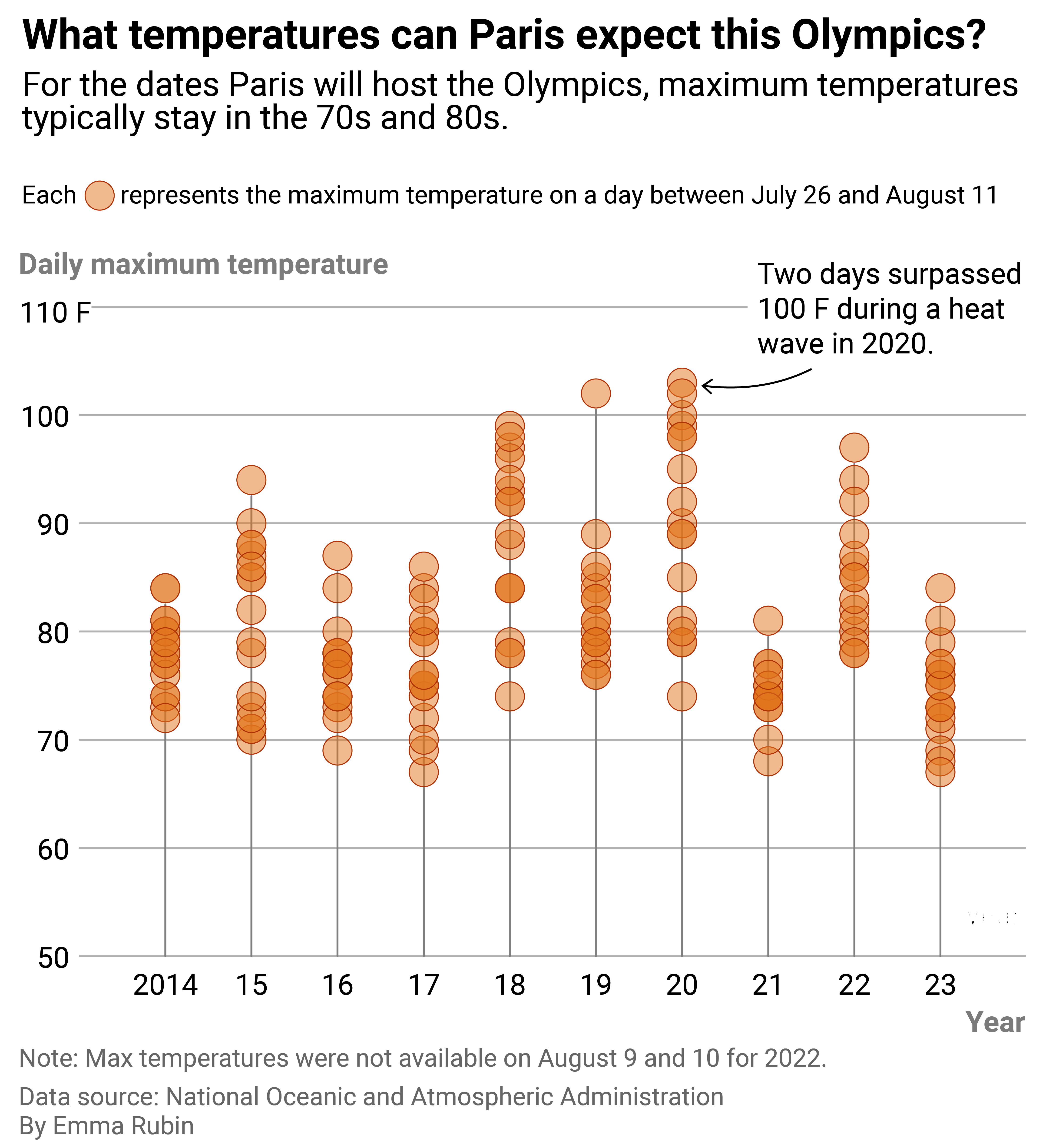

Will Paris 2024 be the hottest Olympics on record?

Chart showing daily maximum temperatures in Paris on the days it will host the Olympics over the past decade. Maximums often climb into the 80s, but heatwaves have struck and in 2020 max temperatures surpassed over 100 Fahrenheit during two days.

According to NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information, 2023 proved to be the hottest year on record, and 2024 is on track to do the same. Europe is the fastest-warming continent on the planet; each of the 12 months since June 2023 was the hottest on record, according to the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service.

The effects of extreme heat have been dire: Places like New Delhi and Greece have reported heat-related deaths in the summer months this year, and more than 1,000 people died in June during the Hajj, the annual pilgrimage for Muslims to Mecca, when temperatures peaked around 125 degrees.

In an effort to lower its carbon footprint, the 2024 Games sets a sustainability gold standard

While the model of the Games hasn’t really changed, University of Toronto professor Madeline Orr noted that some resource-intensive hosting elements have included using existing venues instead of building new ones and thinking more about energy usage, waste, and procurement.

The International Olympic Committee recognizes the role of the Games in climate change and is working to build a more sustainable future for the Olympics. The committee has aligned with the Paris Agreement to tackle climate change, and also put a cap on the number of participating athletes in an effort to curb the carbon footprint of the Games. Paris 2024 plans to welcome about 10,500 athletes from 184 countries—over 900 fewer athletes than Tokyo 2020. However, it’s still far more than the last time Paris hosted the Olympics in 1924 when just over 3,000 athletes competed.

Orr explained that coaches, support staff, and hundreds of thousands of fans contribute to a much larger carbon footprint. “That’s the big problem because that fan travel is fundamentally the biggest challenge in the current model, and nothing about how hosting is happening is addressing that.”

Paris is using existing or temporary infrastructure for 95% of the venues needed for the 32-sport program, taking advantage of already-constructed venues nationwide. The city built two new sports venues and the athletes’ village; organizers used sustainable construction methods and installed recycled materials, such as seating made from recycled plastic. Policies were also developed to cut carbon emissions by using more plant-based ingredients and sourcing food within a 250-kilometer radius (about 155 miles).

“For a really long time, the idea was you build the city to meet the needs of the Games,” Orr said. “And now we’re thinking about building the Games to suit what’s already in the city.”

Spectators can bring reusable water bottles into venues, which will not sell single-use plastic bottles. In a more controversial move, the Olympic Village for athletes was set to use a geothermal cooling system and fans instead of air conditioning. After an outcry from many athletes, the U.S. and at least eight other countries plan to secure AC for its athletes, and organizers ordered 2,500 air conditioners for the village.

If Paris 2024’s sustainability measures prove successful, it could set a precedent for future host cities. Still, the challenges a warming climate poses to athletes are only growing.

What does the future hold for Olympians?

The 2028 Summer Olympics will be in Los Angeles, another urban heat island. In July, a heat wave in the region pushed temperatures past 100 degrees. Organizers for those games have already implemented a venue plan that calls for no new permanent venue construction, continuing hopes that the Olympics can shrink its carbon footprint in alignment with the IOC’s agenda.

Aggressively sustainable venue plans, water refill stations, and other carbon-curbing measures are all practical solutions. However, these stopgap measures won’t ultimately protect future Olympians from the mounting effects of climate change. As temperatures continue to climb, the grueling training modifications, long-term impact on the body, and potential health risks of heat exposure will make elite athletics even more demanding—and riskier. For now, winning or losing may hinge, in part, on learning to compete in and recover from extreme heat.

With the Paris Games underway, attention will soon turn to Los Angeles. Four years from now, let’s hope a race or a match is all that athletes stand to lose.

Story editing by Alizah Salario. Additional editing by Nicole Caldwell and Paxtyn Merten. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.