A death sentence: Native Americans shut out of the nation's liver transplant system

Sharon Chischilly

A death sentence: Native Americans shut out of the nation’s liver transplant system

Lee Yaiva who has lost siblings to liver disease and alcoholism

Native Americans are far less likely than other racial groups to gain a spot on the national liver transplant list, despite having the highest rate of death from liver disease, according to an analysis of four years of transplant data by The Markup and The Washington Post.

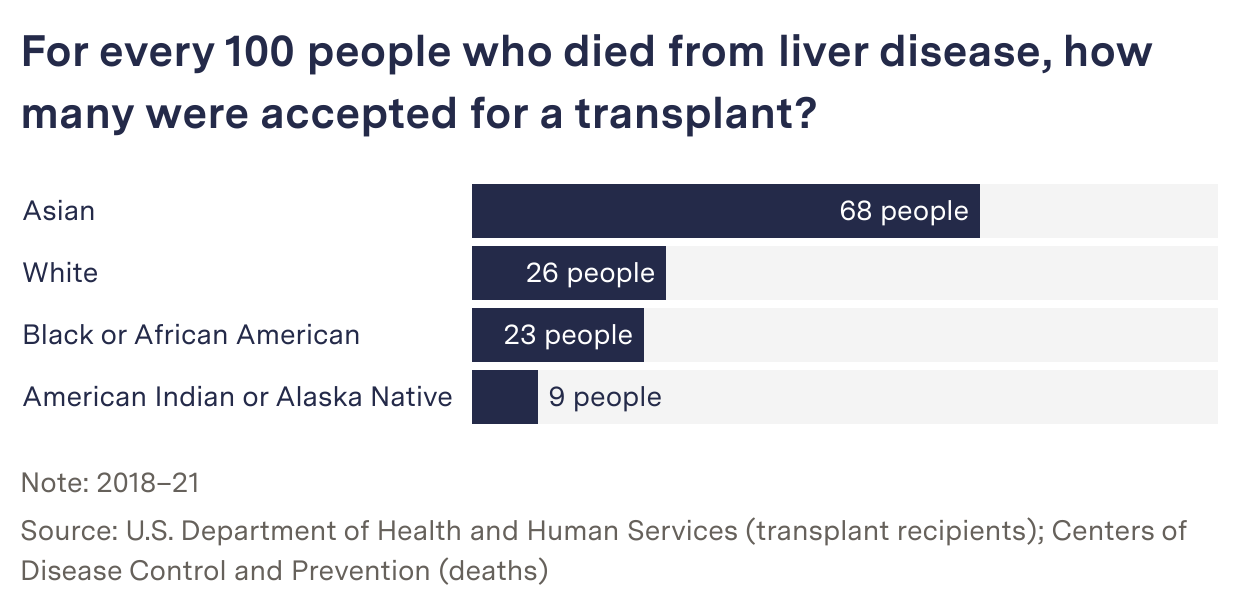

Compared with their total number of deaths from liver disease, White people gain a spot on the transplant list almost three times more often than Native Americans, the data shows. Had transplant rates been equal, nearly 1,000 additional Native people would have received liver transplants between 2018 and 2021.

Native Americans who do win a spot on the list advance to surgery at about the same rate as White people, showing that list access is a primary driver of disparity. Among other racial groups, the liver transplant acceptance rate for Black people is slightly lower than for White patients nationally, while Asian Americans have the highest rate of acceptance to the transplant waitlist by far.

These findings come as mortality from liver disease is climbing across the nation, hitting nearly 57,000 deaths in 2021, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Liver disease is commonly caused by obesity, hepatitis C, and alcoholism. Researchers have attributed the rise in mortality to increased heavy drinking during the pandemic, especially among young people.

Data show poor access to inpatient treatment for alcoholism for tribes across the country. The only cure for end-stage liver disease is a transplant. And getting on the list typically involves a referral by a doctor, which can be hard for those with limited resources to access.

Architects of the U.S. transplant system have wrestled with how to equitably distribute the scarce resources since the program’s inception 40 years ago, concerned that organs would flow to the privileged. Yet, decades later, inequities persist.

Liver disease deaths have long been an epidemic in Indian Country, where Native Americans are four times more likely to die from the disease than non-Hispanic White people, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. It is the second leading cause of death among Indigenous men ages 35 to 44.

[pictured above: Lee Yaiva, a member of the Hopi Reservation in Arizona.]

![]()

Sharon Chischilly

When liver disease hits tragically close to home

Lee Yaiva shows a photo on his phone of his late brothers, who died from liver disease related to alcoholism

Lee Yaiva said every time he went home to the Hopi Reservation in northeastern Arizona, he found that alcoholism had claimed another victim. In July 2022, it was one of his brothers, then in his early 30s. A month later, a second brother died at 29. [In the photo above, Lee Yaiva shows a photo on his phone of his late brothers.]

Yaiva said both brothers were aware their drinking had taken a toll on their livers. The family declined an autopsy in the first death. In the second, doctors confirmed the brother’s liver had shut down. While cleaning out his house, Yaiva discovered dozens of empty bottles of cough syrup, one of the only sources of alcohol on a reservation where it’s not sold.

Living on a rural reservation without cars of their own, the brothers found it difficult to get to the local Indian Health Service clinic, the only medical care Yaiva said his brothers received. Getting to a transplant center in Phoenix four hours away was unthinkable. He said his brothers never considered a transplant. As far as he knows, the option was not offered.

Yaiva believes poverty was part of the reason his brothers died untreated. Transplant professionals agree poverty can be a barrier, with lack of paid time off and unreliable transportation as other factors.

“They kind of accept” death, he said. “It has a lot to do with self-worth.”

Loretta Christensen, IHS’s chief medical officer, said liver disease patients from Indian Country are often diagnosed late, limiting their options. And they may not know that a liver transplant is a possibility.

“We need to increase public education,” Christensen said. “We certainly want those who may need a transplant to get that information.”

For this story, The Markup and the Post compared national transplant figures with an indicator of transplant need: the rate of liver disease mortality for each racial group, as measured by the CDC. The results: For every 100 Asian people who died from liver disease, approximately 68 patients were accepted for a transplant from 2018 to 2021. Among White people, 26 patients were accepted; among Black people, it was 23. (Latinos, who are assigned to various racial groups in the data, are excluded from this analysis.)

The Markup

From 2018-2021, among Indigenous people, just nine patients were accepted for a transplant for every 100 who died from liver disease

Bar chart: For every 100 people who died from liver disease, how many were accepted for a transplant?

“The unevenness in access and outcomes is a problem for all of us,” said Dr. Jewel Mullen, who has examined disparities in organ transplants and is the associate dean for health equity at University of Texas at Austin’s medical school.

“They limit our ability to be as healthy as we can be as a society. And I want to believe that at our core [there] is still some fundamental belief in fairness.”

In some parts of the country, racial disparities appeared particularly stark. In Washington D.C., and Arkansas, for example, White people were twice as likely as Black people to be added to the liver transplant list when compared to their rates of death from liver disease.

“It’s not like people saying, ‘Oh, you are Black, you aren’t going to get it,'” said Dr. Nikhilesh Mazumder, a gastroenterologist at University of Michigan Health. Mazumder believes it’s more that the history of race in America—and its persistent connection to poverty—has “ended up stacking the deck against referral.”

And even small national differences can add up: An estimated 430 additional Black people would have been accepted for liver transplants from 2018 to 2021 had national transplant rates been equal.

A history of problems

In 2022, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine reported that an individual’s chance of being added to the transplant list “varies greatly based on race and ethnicity, gender, geographic location, socioeconomic status (SES), disability status, and immigration status.”

Kenneth Kizer, who chaired the report’s committee and is best known for reshaping the Department of Veterans Affairs in the 1990s, said “the responsibility lies with HRSA,” the Health Resources and Services Administration, an agency under HHS.

Kizer is not alone in that assessment. When Congress established the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network in 1984 to oversee the allocation of the nation’s organ supply, lawmakers mandated that a task force convene to make “recommendations for assuring equitable access.”

“We were trying to make sure it would be available for everybody regardless of race or income,” said former Oklahoma senator Don Nickles, a Republican who co-sponsored the legislation. “We wanted the opportunity to be there to save lives.”

For decades, federal law has required the network to increase transplantation among “racial and ethnic minority groups and among populations with limited access to transportation,” but neither the network nor its administrator, the United Network for Organ Sharing, pointed to efforts they’d made to address inequities in access to the liver transplant waitlist.

Since 2000, HHS has required the network to collect information about “patients who were inappropriately kept off a waiting list,” but it has never happened.

“If we don’t have that data, we are not going to be able to understand where to intervene,” said Rachel Patzer, an epidemiologist who leads health research organization the Regenstrief Institute and former chair of the organ network’s Data Advisory Committee. Patzer pushed for 15 years to jump-start the data collection process but said she was stymied by red tape.

Anne Paschke, a spokesperson for the United Network for Organ Sharing, agreed that the data is crucial but said her organization doesn’t have the authority to collect it; HRSA spokesperson Martin Kramer did not dispute the claim that it’s holding up data collection and did not answer questions about the more than two-decade delay.

Kramer said in a written statement that the agency is undergoing the “most significant overhaul … in decades,” including plans to improve data collection.

“In order to improve waitlist access for people of color, we first need to better understand why access issues persist and have the legal authority to act on our findings,” she said in a statement.

“Letting a lot of young people die”

Experts say data about who is denied transplants could shine a spotlight on inequities at transplant centers.

Because organs are in short supply nationally, transplant teams are selective about who is placed on the list. But no federal rules require transplant centers to make their selection criteria public.

Two centers acknowledge that they will not accept patients with alcohol-associated liver disease unless they are six months sober. The rule stems from fear the new liver would be destroyed by continued drinking. But doctors began abandoning this policy more than a decade ago after research showed that carefully selected patients who had not established six months of sobriety before the transplant were nonetheless thriving two years after receiving a new liver.

More than a dozen other centers either declined to provide their policies or did not respond.

“We were letting a lot of young people die who really should have been transplanted,” Russell Rosenblatt, a transplant hepatologist at Weill Cornell Medicine, said of the six-month rule.

Changes in national policy can improve equity. Prior to 2002, data showed that Black patients were more likely than White patients to die waiting for a liver transplant. Then, transplant centers rolled out a new way of measuring the severity of the disease so sicker patients could be identified and given higher priority. A study published in 2008 in the influential journal JAMA found this new measurement—known as the MELD score, for Model for End-Stage Liver Disease—radically improved outcomes for Black people on the liver transplant list, wiping out their disparities in deaths in the four years examined.

Donna Cryer, who leads the nonprofit Global Liver Institute, said inequity begins long before a transplant becomes necessary. Patients without access to regular primary care may not be screened for liver disease. The disease is often treated by gastroenterologists or hepatologists, who in turn make referrals to transplant centers when a patient’s illness becomes life-threatening.

“We see a lot of patients drop off” at the specialist stage, Cryer said. “The incentives on finding more people are not there.”

Several experts said lacking reliable transportation and living far from a transplant center can also put the surgery out of reach. Patients on the transplant list must be able to get to routine exams and care leading up to their surgery, and they need to be able to get to a hospital at a moment’s notice should an organ match become available. Patients sometimes move to live closer to their hospital for this reason—if they can afford it.

Sharon Chischilly

Devastation on reservations

Lee Yaiva is CEO of Scottsdale Recovery Center, which offers culturally informed, inpatient programs for Native American clients

In August, Yaiva, the Hopi citizen, was shattered to learn that a third brother had been found dead a week before his 38th birthday.

Though the family again declined an autopsy, Yaiva said, he again suspected that years of alcoholism had taken its toll. Near the end, yellowed skin and a bloated body had put the often silent, slow-moving disease on sickly display.

“I feel bad for my mom,” he said. “It’s a constant tragedy.”

Yaiva won his own battle with alcoholism a decade ago and went on to become CEO of Scottsdale Recovery Center, which offers culturally informed, inpatient programs for Native American clients.

While the Affordable Care Act now requires insurance to cover substance use disorder treatment, Yaiva said, many Native Americans struggle to pay for sober housing and other care. One in four Indigenous Americans lives in poverty, according to census data, the highest of any racial group.

Citizens of recognized tribes have a right to free health care under federal law. Still, the Indian Health Service fails to provide services needed at many stages of liver disease and substance use disorder treatment, its data show.

Though the agency serves a population of 2.6 million people with the highest rate of drug- and alcohol-related deaths in the U.S., IHS paid claims for inpatient substance use treatment for just 18 patients a year on average from 2018 to 2022.

“The whole country is not getting the addiction treatment that they need broadly, but particularly in Indian Country, there are huge health disparities,” said Monica Skewes, a psychology professor at Montana State University and investigator at the Center for American Indian and Rural Health Equity.

IHS outsources most substance use treatment to tribal programs, but the quality varies. The Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation in North Dakota, known as the MHA Nation, is wealthy from oil and gas revenue, and has its own inpatient and sober living facilities.

But on the Montana reservation where Skewes works, she said, counselors with little training provide outpatient care. When she began a pilot substance use disorder program there, community members asked that participants be served full meals instead of snacks, quadrupling the food budget.

“Otherwise, they are literally too hungry to pay attention,” Skewes said.

IHS has long struggled to pay for services outside its hospitals and clinics. “Many sites were limited to authorizing payment solely for life and limb-threatening emergencies,” IHS spokesperson Nicole Adams said in a written statement.

Adams said recent changes, including the implementation of Medicare-like reimbursement rates, has allowed the agency to stretch its dollars further and provide more services. Lack of substance use treatment is “profound in Indian Country in rural and extreme rural areas,” she said, and it’s a “pressing challenge” for the agency. She declined to comment on whether the liver disease care it currently provides is adequate.

IHS officials have repeatedly asked for more federal funding, arguing that it is forced to defer tens of thousands of patients’ requests annually for everything from eyeglasses to treatment for sexually transmitted diseases. IHS’s data show the agency deferred nearly 113,000 patient requests to see specialists from 2018 to 2022, including 6,196 requests to see gastroenterologists.

Hepatologists also treat liver disease, but deferrals for that specialty are not broken out in IHS records. However, agency data show it paid claims for just 226 patients a year to see hepatologists, on average. Rates were similar for gastroenterologists.

IHS patients may sign up for Medicaid or Medicare or seek insurance through Affordable Care Act marketplaces—something IHS staff routinely recommend. When a patient has access to other coverage, IHS becomes the payer of last resort.

Claim data shows the agency chipped in very little to the cost of liver transplantation, averaging $11,200 per patient. That is about 2% of the $650,000 billed for the average procedure, according to the actuarial and consulting firm Milliman. With medication, recovery, and other costs, the price can soar to nearly $900,000.

From 2018 to 2022, the agency kicked in funding for just six liver transplants. During the same period, it deferred 105 requests for transplants of all organ types.

Adams, the IHS spokesperson, said some requests that are initially deferred may be approved later.

Scarcity extends beyond IHS. Large swaths of the country have no liver transplant centers, including the Dakotas, Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho, states that are home to more than two dozen Native American reservations.

Monica Mayer, a Tribal Business Council representative for the MHA Nation and a former IHS physician, has seen firsthand what happens when liver disease is not treated in its early stages. Patients show up in the emergency room, well past the point when their lives could have been saved.

“IHS is not doing a good job of taking care of us,” she said.

Mayer eventually rose to become chief medical officer of the IHS Great Plains Area before serving in tribal government. She said better addiction services are essential to stopping a “devastating” loss of life that has left some small tribes facing cultural extinction

With every preventable death, she said, “We lose the ability to pass on traditions, our way of life, our language.”

Reporter Malena Carollo contributed to this story.

This story was produced by The Markup and reviewed and distributed by Stacker Media.