1 year later: How COP27 countries are pacing on the global methane pledge

Karol Serewis/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images

1 year later: How COP27 countries are pacing on the global methane pledge

Burning flare at an oil extraction area against sky

During the 26th Conference of the Parties discussing climate change (COP26), the U.S., EU, and over 100 countries launched the Global Methane Pledge, a nonbinding agreement to reduce human activity-related methane emissions by 30% from 2020 levels by 2030. If followed, it could reduce the rate of global warming by 0.2 degrees Celsius by 2050.

Since then, ruptures from the Nord Stream pipeline caused what may be the biggest methane leak ever detected; 2021 global gas flaring volumes remained steady; and 2022’s atmospheric concentration of methane reached a new peak. Methane—the second-most abundant greenhouse gas–lasts in the atmosphere for less time than carbon dioxide, but has at least 25 times the heat-trapping power. Curbing methane emissions is one of the most immediate factors that can mitigate near-term warming and other climate change-related events.

World leaders have recognized the importance of cutting methane emissions, but the gas’s far-reaching presence—from the agricultural industry to landfills to the energy that powers electric grids across the world—has made it a daunting task. Still, implementing certain practices, policies, and other initiatives can significantly reduce emissions. Seventy percent of methane released by the fossil fuel sector alone may be preventable.

“It really is inspiring and historic to see the conversation that our world leaders are having and keeping the spotlight on methane and recognizing the near-term importance of change,” Felicia Ruiz, Director of International Methane Partnerships and Outreach at Clean Air Task Force, told Stacker.

Stacker cited data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the International Energy Agency, and the Earth Observation Group to visualize global methane emissions and explore international efforts to reduce methane emissions 30% by 2030.

You may also like: A history of US military aircraft

![]()

Emma Rubin // Stacker

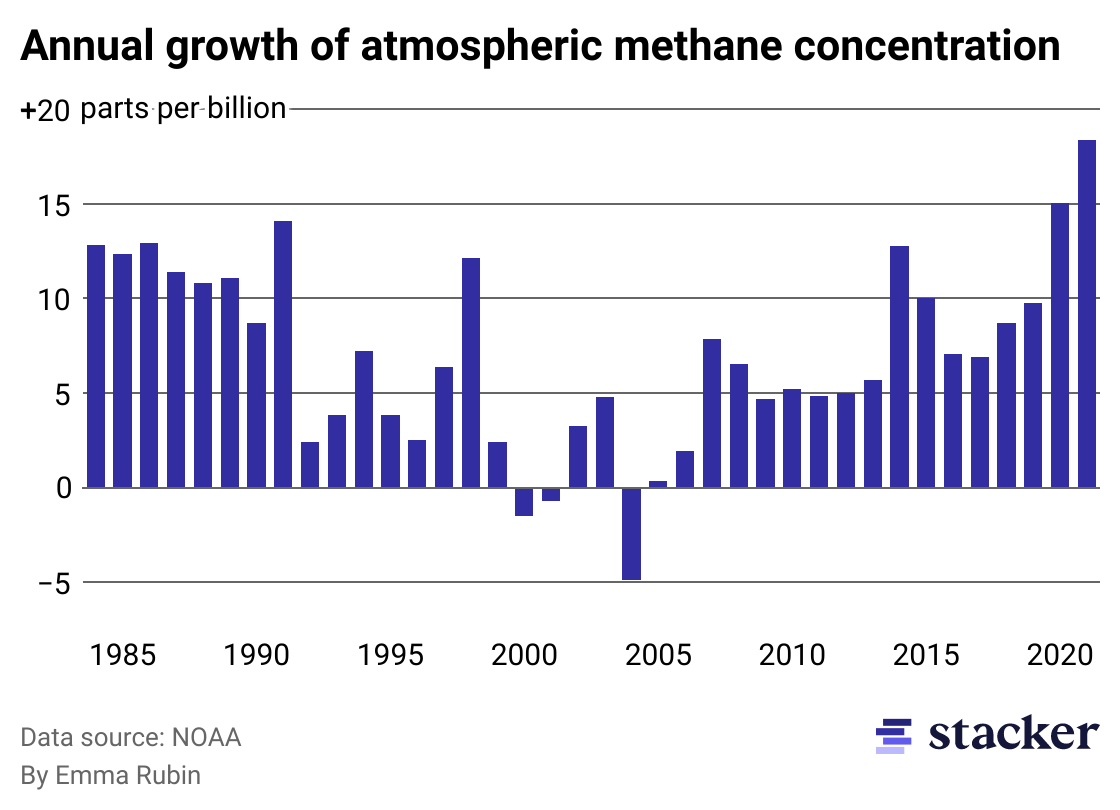

Atmospheric methane has increased continuously since 2005

Column chart showing change in atmospheric methane emissions by year. 2021 showed the greatest change.

Since NASA began tracking methane in the 1980s, concentration of the greenhouse gas has grown consistently other than a brief period in the early 2000s. Chemical analyses of methane isotopes suggest that recent increases may be attributed to releases from thawing permafrost and methane hydrate.

This increasing concentration of methane has the potential to unleash what some climate scientists have called a “methane bomb.” Warming from methane and other greenhouse gases promotes the release of additional methane in Arctic regions, perpetuating the warming cycle and potentially even an extinction event akin to one that took place over 250 million years ago. Opportunities to stop methane from releasing in already-thawing Arctic regions is limited, but curbing emissions from other sources can slow the warming that causes it.

Emma Rubin // Stacker

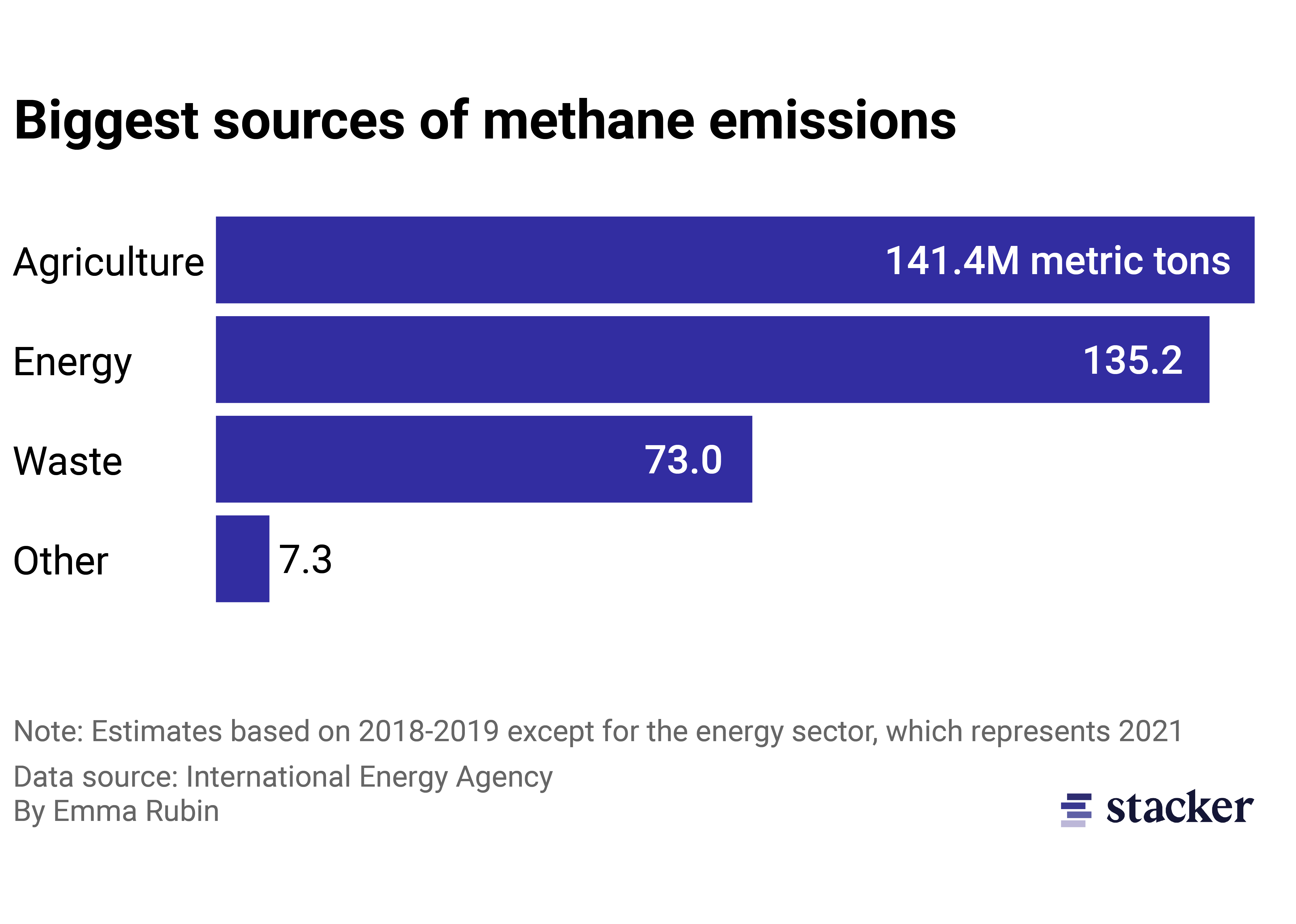

Agriculture and energy contribute the most to global methane emissions

Bar chart showing methane emissions by sector including agriculture, energy, waste and other

Emissions related to livestock digestion, particularly among cows and other cud-chewing animals, have been one of the greatest contributors to methane concentration. An estimated 7.1 gigatons of CO2 equivalent are released annually from animal agriculture, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization. Methane emissions from animal agriculture have proven difficult to manage. Research testing methane-inhibiting compounds and selective breeding have shown microbes that produce methane soon rebound, though research to mitigate emissions beyond overall reduction of livestock is ongoing.

Globally, rice cultivation is also a significant contributor. Alternate wetting and drying, where rice paddies are kept dry between harvest sowing, could reduce rice-related methane emissions by 48%. Vietnam, the fifth biggest rice producer in the world, is developing new guidelines to improve irrigation systems, support alternative crops, and manage waste. The country emitted 47.3 million tons equivalent CO2 from rice production in 2020, representing 43% of its methane emissions, but still a fraction of the global total.

In the energy sector, oil, gas, and coal production are the largest sources of methane emissions. In the oil and gas sector, minimizing venting and flaring and updating equipment can prevent excess emissions. In abandoned and closed coal mines, methane can be recovered and used for energy needs. “Not taking advantage of the methane that is being put into the hemisphere is really a wasted use of a very valuable energy source,” Ruiz said.

Emma Rubin // Stacker

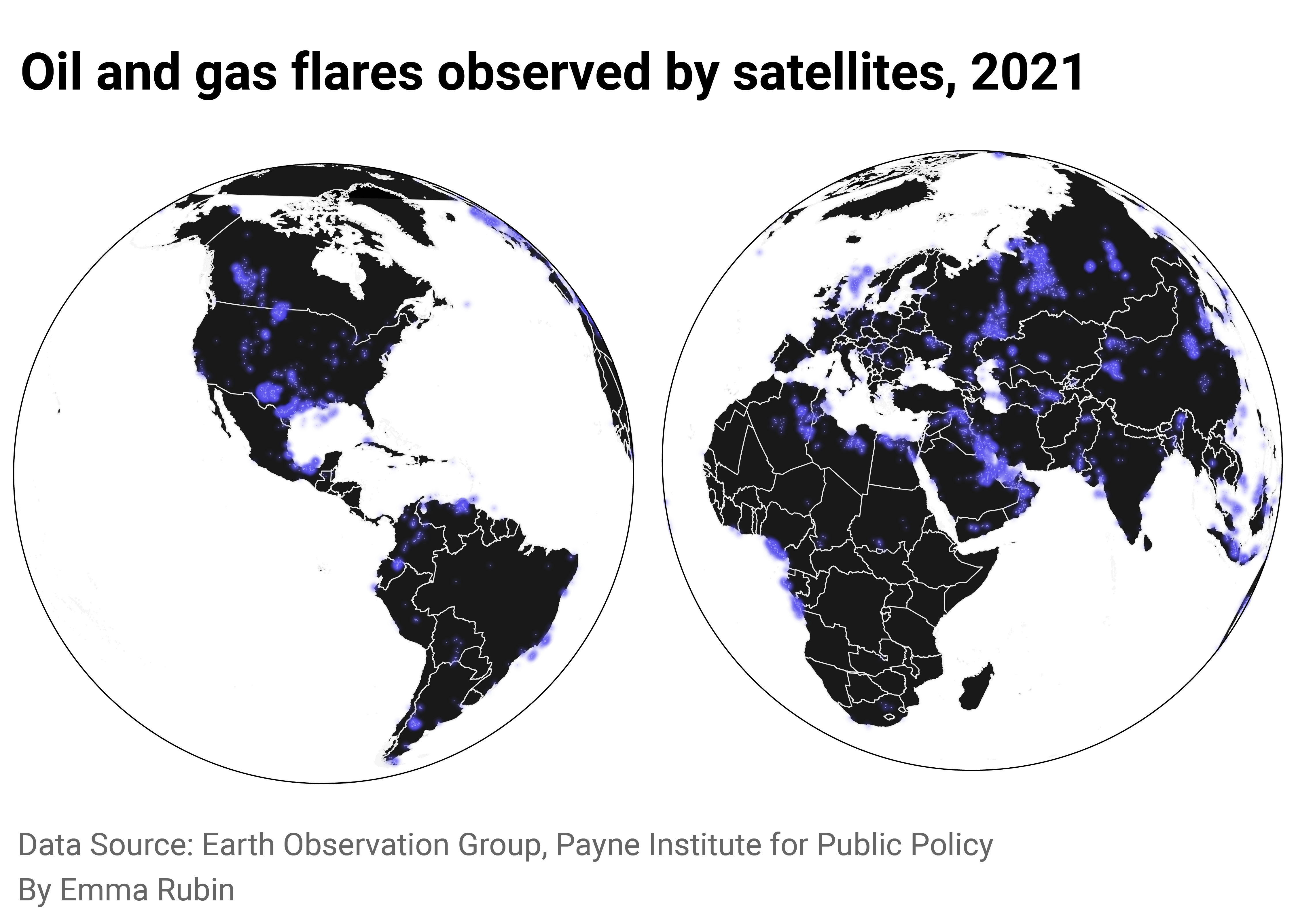

Satellite imagery shows the spread of flaring by the oil and gas industry

Global map showing dots where gas flaring happened during 2021

Over 5 trillion cubic feet of gas are flared annually, according to the World Bank. Calculations show that approximately every 6 cubic feet is associated with 1 pound of CO2 equivalent emissions. Satellite-tracking efforts by NASA, NOAA, and other partners capture when and where flaring is happening. Dots trace the outline of the Bakken oil field, productive basins in Siberia, and offshore facilities near coastlines.

Oil companies are largely responsible for flaring and venting, relying on the practice to safely manage variations in pressure at rigs and other parts of the supply chain. Because of oil’s profitability, investing in equipment, outreach, and infrastructure to capture and sell what’s considered waste, but is otherwise a valuable resource, is not a priority.

Emissions from flaring per barrel of oil have fallen over the past 20 years. Still, the increasing production has offset the per capita decrease, and methane emissions from flaring and venting have remained mostly steady over the past 10 years. The latest data for the U.S., however, shows it reduced its total flaring intensity even as oil output grew.

Emma Rubin // Stacker

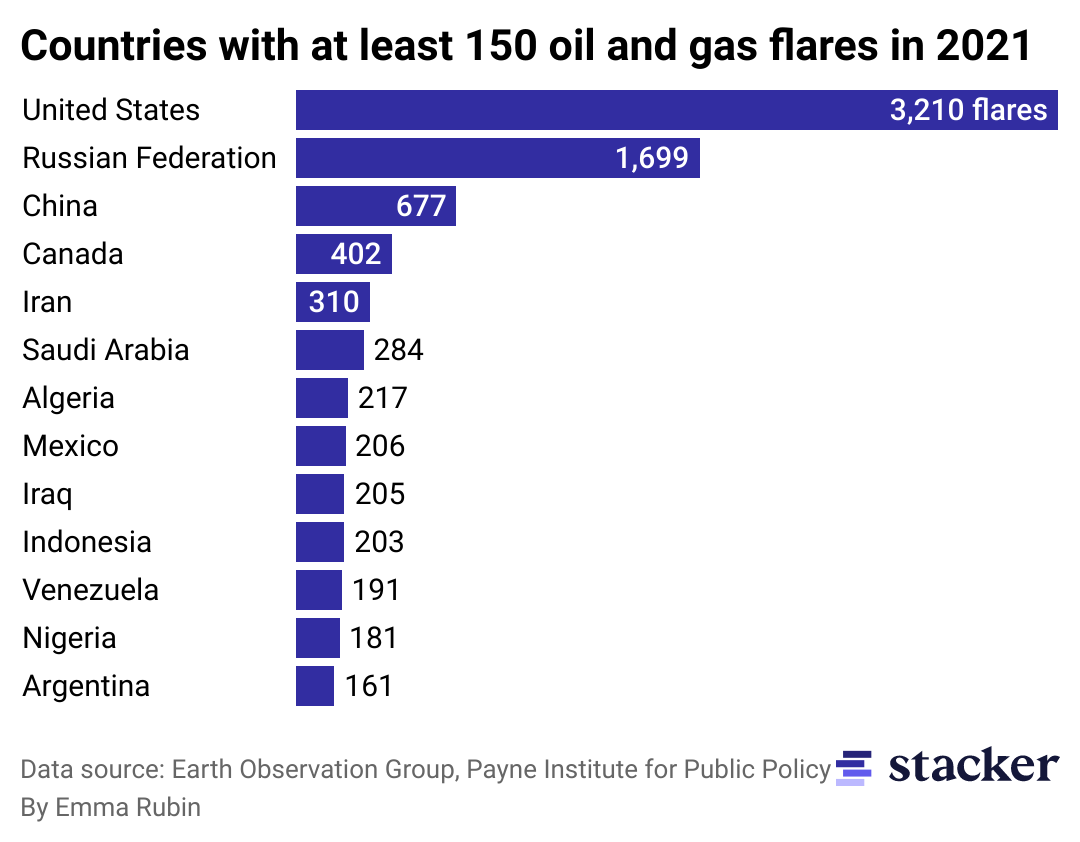

Oil and gas companies drilling in the US were responsible for the most flares in 2021

Bar chart of gas flaring by country of location.

While the flares were smaller and more irregular in frequency than those in Iran and Russia, the U.S. was home to the most flaring sites in 2021. Estimates from the World Bank show companies flared over 309 billion cubic feet of gas in the U.S. in 2021.

The Inflation Reduction Act outlined the Methane Emissions Reduction Program, which taxes companies for excess methane emissions, charging $36 per metric ton of CO2 equivalent beginning in 2024, and increasing to $60 by 2026. The program also revises EPA’s greenhouse gas reporting program to require data over self-reported estimates for company emissions, and allocated over $1.5 billion to mitigate emissions through technological improvements and well management.

Norway, which implemented a tax on methane to reduce flaring in 1990, has seen a decline in related emissions by 80% since then, according to the International Energy Agency. Nigeria set a target to reduce 60% of fugitive emissions by 2031, while Iraq is aiming to eliminate the process by 2027.

Emma Rubin // Stacker

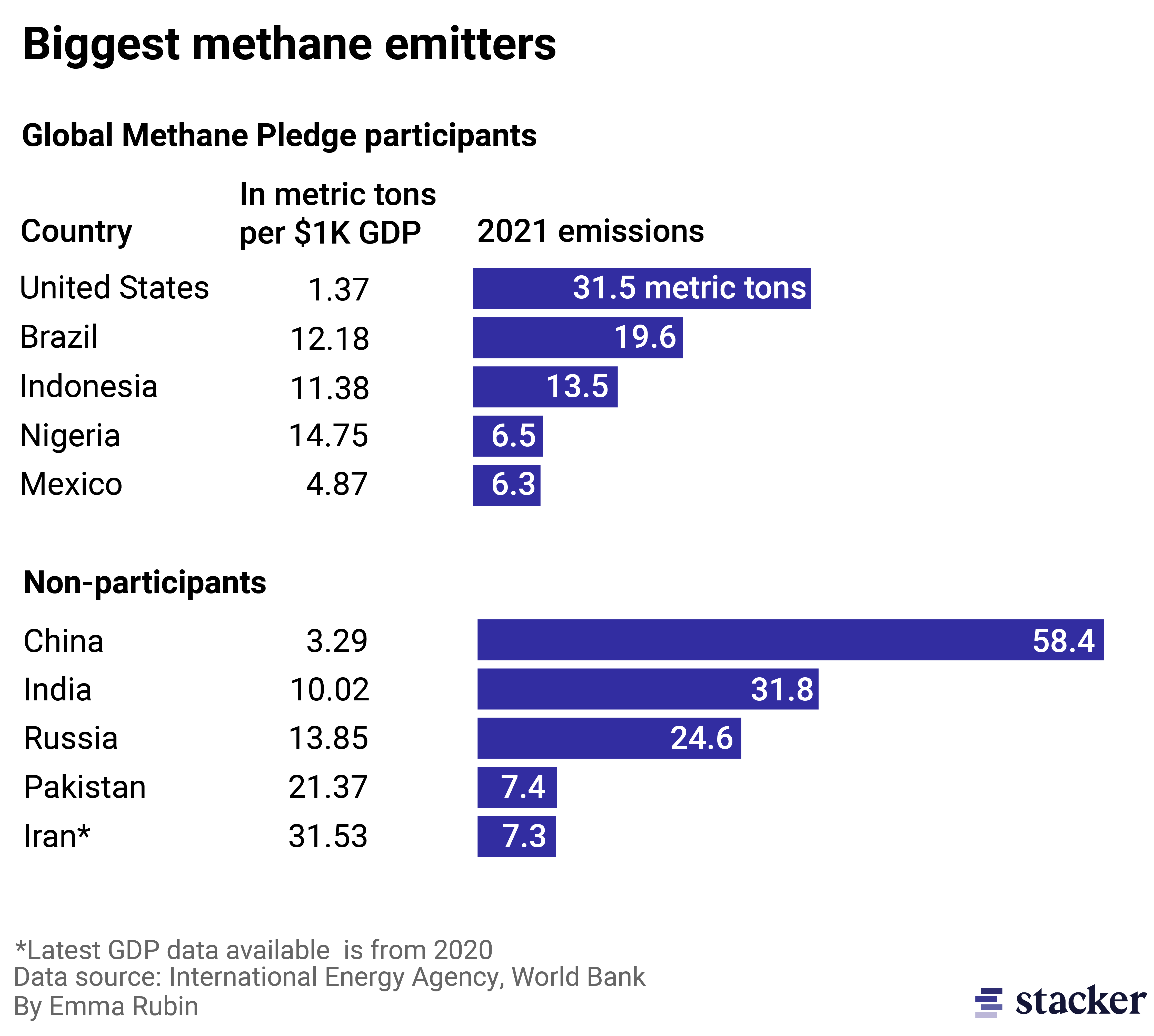

Half of the biggest methane emitters are not part of the Global Methane Pledge

Bar chart of the 10 biggest global methane emitters which includes US, China, India and Russia.

Russia, China, and India are among the top five largest global emitters of methane, but none have signed on to the Global Methane Pledge. The majority of emissions in India and Pakistan come from agriculture, and China’s are largely related to agriculture and domestic coal production. Australia, another major emissions contributor from coal, is also absent from the pledge. For Russia and Iran, significant emissions come from the energy production process—energy sometimes exported to methane pledge participants.

The European Union’s methane regulation proposal released after COP26 set fixes and expectations for domestic methane emissions, but it notably left out regulations targeting imported oil and gas, the source for most of the region’s emissions. “In 2021, there was minimal political appetite from member states to risk the plentiful and cheap supply of energy into Europe, despite repeated calls from the European Parliament, a situation that has been entirely shaken up by the invasion of Ukraine,” Alessia Virone, Government Affairs Director for Clean Air Task Force, told Stacker.

Europe’s weaning off Russian gas has the potential to reduce imported methane emissions. The EU is relying more heavily on gas from Norway, Algeria, and the U.K., but still received over half of its natural gas imports from Russia in the second quarter of 2022. A recent proposal, RePowerEU, takes a more targeted approach to emissions from imports under the “You Collect, We Buy” initiative, seeking to purchase gas that would otherwise be flared or vented from new energy partners. “If implemented, it would be genuinely a world-leading proposal, but we are yet to see concrete details of how it would work,” Virone said.

You may also like: Iconic buildings that were demolished