With all eyes on the Big Dance, Wall Street trades slow during March Madness

Tom Pennington // Getty Images

With all eyes on the Big Dance, Wall Street trades slow during March Madness

The Kansas Jayhawks celebrate with the 2022 NCAA trophy.

There’s a reason it’s called March Madness.

Much like the Olympics or World Cup, the NCAA Division I men’s basketball tournament is a major sporting event that draws significant viewership, even for games played during normal working hours. That makes it difficult for even the most dedicated employees to keep their focus on work.

Last year, college basketball’s Big Dance averaged 10.7 million total television viewers for its live game telecasts, with the Kansas Jayhawks’ 72-69 championship game victory over the North Carolina Tar Heels pulling an average of over 18 million viewers on TBS, TNT, and truTV. Even nonsports fans get in on the action with office brackets, which arguably take little to no skill to fill out, let alone win, but allow people to have some skin in the game.

“It’s hard to find somebody who doesn’t know a friend who’s filling out a bracket,” Rodney Paul, a sports analytics professor at Syracuse University, told Stacker. “It’s pretty easy to be able to get involved, especially with something that there’s no stakes or low stakes.”

To quantify March Madness’ effect on productivity, Stacker looked to the stock market, collecting trading volume data from the Chicago Board Options Exchange between 2009 and 2022. We found more often than not, trade volume dipped at the start of the tournament. Trade volume was measured as the sum of shares exchanged during trading hours on all U.S. equities exchanges and trade-reporting facilities during trading hours. Our full findings lay ahead.

You may also like: History of the NFL from the year you were born

![]()

Jared Beilby and Elena Cox

Traders take pause

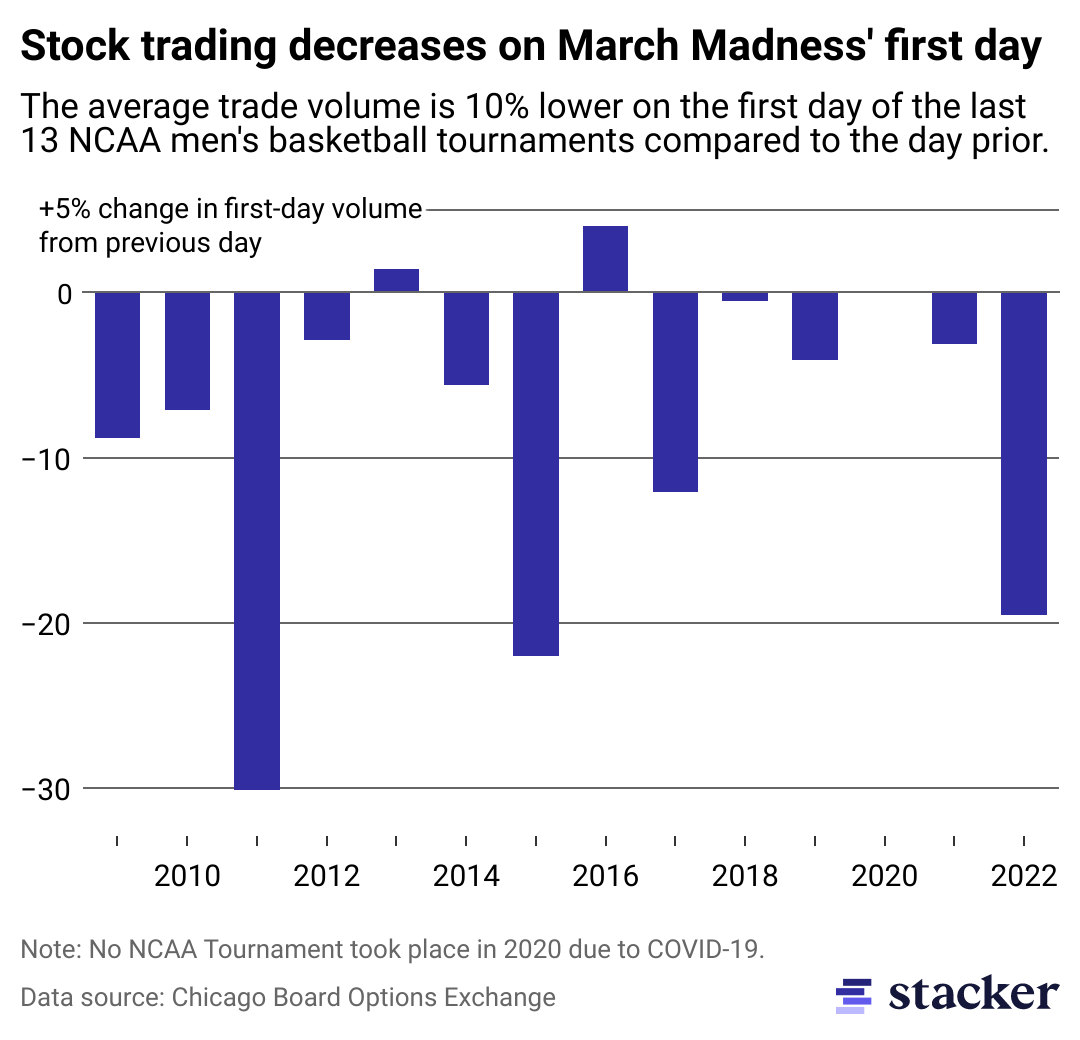

Column chart of the percent change of stock trades between the first day of March Madness and the day prior.

In 11 of the last 13 years the NCAA Division I men’s basketball tournament took place, the number of shares traded during the tournament’s first day decreased compared to the day before. This goes against the typical trading pattern.

Usually, the number of shares traded daily steadily rises throughout the week before slouching on Fridays. From Wednesday to Thursday (the typical tournament start day), the number of shares traded increases by 0.8% on average, according to trading data going back to October 2007. During March Madness, however, the trend flips: The number of shares traded on the tournament’s first day is an average of 10% lower than the day prior—a nearly 11 percentage-point swing.

Looking at data from the first day of the tournament is especially crucial. Both the opening and second days are March Madness’ busiest—there are 32 games played between the first two days, with the earliest tipoffs happening around noon ET. Because so many games take place during work hours, the start of the tournament is when productivity could take the biggest hit.

orhan akkurt // Shutterstock

Explaining the outliers

Traders on the floor of the New York Stock Exchange.

On the floor of the New York Stock Exchange in Manhattan, it’s not uncommon to see traders have at least one of their many screens tuned into the games. Though most traders are used to being in a high-pressure, reactive environment.

Many games are scheduled on or around the Federal Reserve’s March meeting, which also happens in mid-March. But usually, their decisions are baked into the market, says Jonathan Corpina, a senior managing partner at Meridian Equity Partners with nearly 25 years of Wall Street experience.

“When you look at the economic calendar, we know there are things coming out. Everyone knows the Fed is going to make an announcement. You probably have your position or bet on what the market is going to do,” Corpina said.

That bears out in the data. The two times the number of shares traded bucked the trend during March Madness and increased were after major and unexpected economic events: the 2013 banking crisis in Cyprus, and a surprise decision from the Fed to cut its rate hike outlook in 2016 due to economic headwinds.

Melinda Nagy // Shutterstock

Despite dipping data, March Madness brings positives

A collage of nine different college basketball images.

However, the data doesn’t tell the full story. Rodney Paul warns that a drop in trading volume doesn’t necessarily equal a loss in productivity across the whole workforce.

“People will project that to a loss of productivity,” he said. “We live in a society where you can really shift your time in different ways, so maybe people start earlier, maybe people don’t take the coffee break that they would otherwise.”

Beyond that, March Madness is an event that can improve workplace dynamics—even if people skip work to tune into games. A 2011 study found that while productivity decreases in the workplace during the games, it’s also a way to bring an office together.

“It’s just something that gets people talking,” Paul said. “It can lead to other things. Because as you’re going throughout the day, you start talking about the game, but it might lead to talking about yourself, your family, etcetera, and other things that build up a deeper relationship.”