Latinos have been the fastest-growing demographic in swing states since the last election. Could they choose the next president?

Photo Illustration by Elizabeth Ciano // Stacker // Getty Images

Latinos have been the fastest-growing demographic in swing states since the last election. Could they choose the next president?

Hand placing ballot into collage of state shapes with “I voted/Yo Vote” sticker and symbolic representations of presidential candidates.

Far from the Southern border states of previous elections, a rush to court Latino votes ahead of Nov. 5 is concentrating in Pennsylvania’s hotly contested “Latino Belt”—and both camps have firmly planted their flags.

In June, the Trump campaign opened an outreach office in Reading, Pennsylvania, home to one of the largest Latino populations in the Keystone State. Nearly 7 in 10 residents of the former factory town are Latino, with many of Puerto Rican and Dominican descent. “Latino Americans for Trump,” and “Stop Illegal Voting” placards in the front window distinguished the office from the surrounding corporate spaces.

Two months later, the Harris campaign opened an office an hour’s drive northeast of Reading in Allentown, where roughly half the city’s population is Latino. Second gentleman Doug Emhoff visited the headquarters in early September, rallying the crowd in front of a decisive sign reading “Cuando luchamos, ganamos”: When we fight, we win.

Reading and Allentown are part of Pennsylvania’s Latino Belt, a nod to the cluster of cities that once made up the working-class, industrial Rust Belt. Factory closures and population declines have made the region one of the more affordable real estate markets in the Northeast, a draw for Latino families from nearby metros seeking homeownership.

Residents leaving expensive urban areas of New York City and Philadelphia readily filled jobs at manufacturing facilities, while newer positions opened at the many logistics and fulfillment facilities serving the Eastern Seaboard—often along the freeways cutting through the outermost bands of Philadelphia’s urban sprawl. Driven by the promise of a better future, the growing number of Latinos who call the region home is a major reason why the former industrial hot spot is now an election front line, with both parties using new tactics to garner votes.

With the election imminent and the presidential race essentially tied, Stacker explored where the highly coveted votes of Latino Americans might swing this November.

Editor’s note: Stacker recognizes that Hispanic and Latino are not interchangeable terms. The usage of Hispanic and Latino are in accordance with the language of the sources included in this story.

You may also like: States where the most Jan. 6 rioters have been arrested

![]()

Stacker

Expanding influence

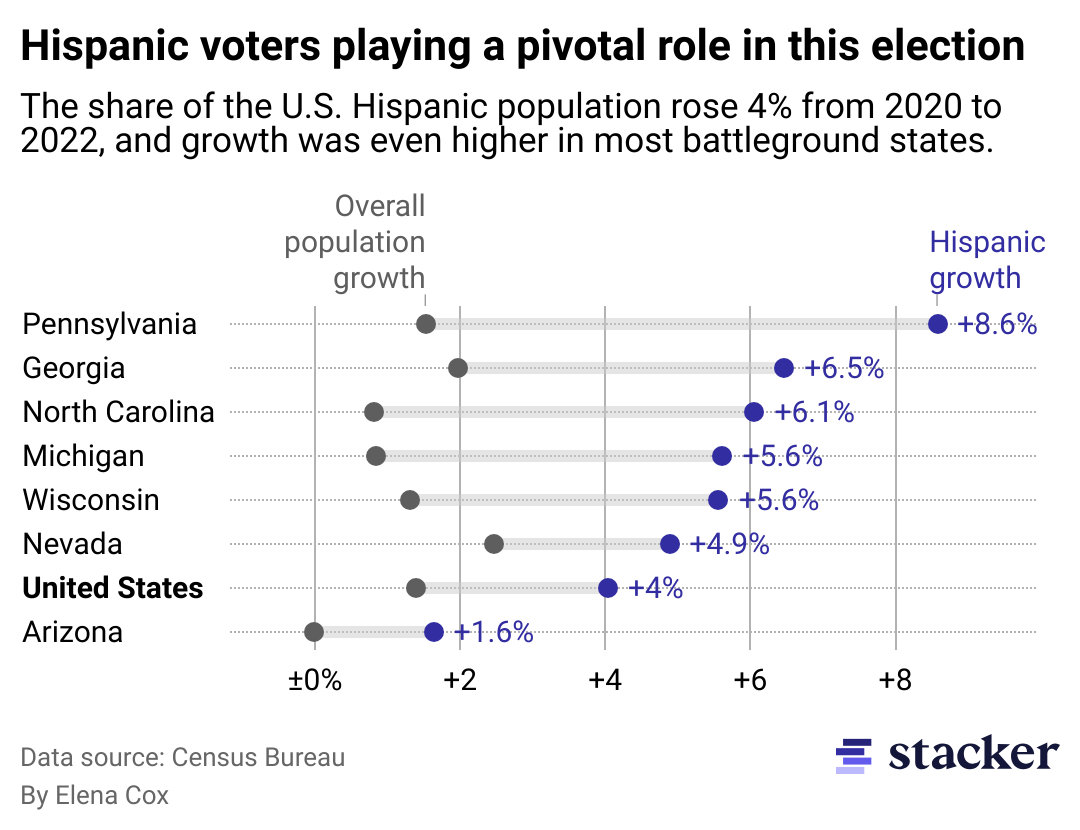

A range plot comparing the overall population growth to the Hispanic population growth in the United States and swing states between 2020 and 2022.

Pennsylvania’s Hispanic population has grown by 8.6% since the 2020 election, making it the fastest-growing among six battleground states with above-average Hispanic population growth since the last presidential election. The number of Hispanic Americans living in the United States reached 65 million in 2023, according to Census data. That increase, fueled by higher birth rates and international immigration, accounts for the majority of the country’s overall population growth from the year before.

“Latinos very particularly believe in the American dream, that’s why so many of them have immigrated here,” political consultant and former Kamala Harris staffer Maria Restrepo told Stacker. “That’s why me and my mom immigrated here.”

Restrepo, a Colombian immigrant who grew up in the now heavily Latino Lehigh Valley region of Pennsylvania, believes that voter turnout will continue to increase alongside a rise in the economic and cultural influence of the area’s Latino population.

Both campaigns still have work to do. Selling their visions to a booming Latino population that has signaled its votes are up for grabs is not a matter of assuming solidarity based on identity or reducing messaging down to a single issue, as previous elections have shown.

Stacker

Dems lose ground even as Harris leads

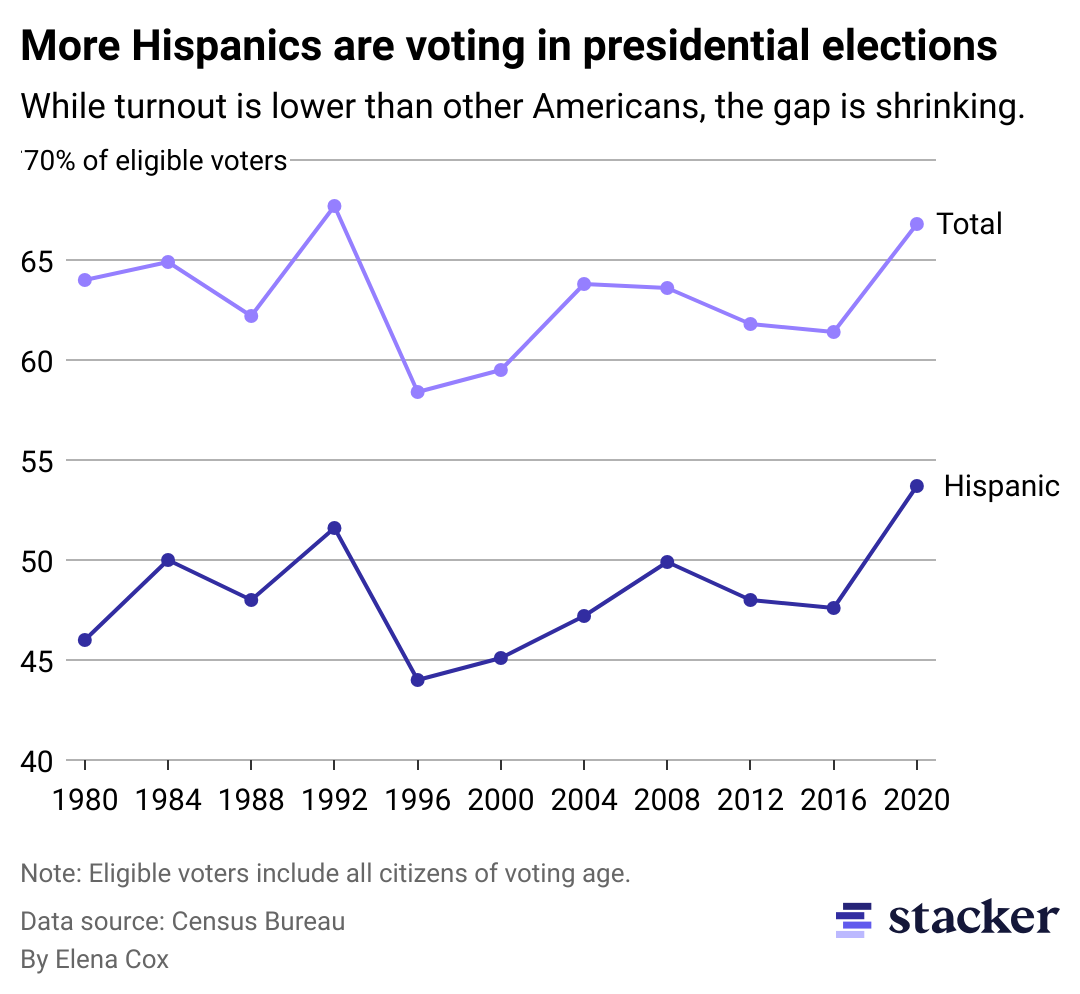

Line chart showing growth of Hispanic voter turnout from 1980 to 2020. Hispanic voter turnout is still lower than the total eligible voter turnout.

Latino communities over the last few decades have grown more politically engaged. Eligible Hispanic voters who cast a ballot grew from 44% in 1996 to 54% in 2020, with the number of eligible voters up 4 million since just 2020. That’s 36.2 million Latino voters—more than twice the number of Latinos who were able to vote in 2000.

Some campaign strategies in this election cycle finally acknowledge that the diaspora of Hispanics and Latinos is not a monolith. The voting bloc comprises recent immigrants and multiple generations descended from immigrants from nearly two dozen countries throughout Central and South America, as well as Spain and the Caribbean.

The Trump campaign’s rebranded Latino outreach effort emphasizing American citizenship is a case in point, as is a new tactic emerging from the Harris campaign: downplaying identity politics and focusing instead on the issues.

In 2020, Hispanic voters made their voices heard amid a pandemic that had an outsized impact on their communities. The election had a record turnout, marking the first time since 1992—when Democrat Bill Clinton beat Republican incumbent George H.W. Bush—that more than half of Hispanic voters participated in the presidential election.

This participation made Hispanic voters a key part of the coalition that delivered Joe Biden and Harris the White House in 2020. Trump, however, made significant inroads: More Latinos voted for him in 2020 than they did in 2016.

A 2021 report from Equis Labs, a Democrat-leaning research firm, found that Trump increased his vote share in densely populated Latino areas in battleground states. In Maricopa County, Arizona, for example, he received 64% more votes than in 2016. In Milwaukee, votes for Trump rose 38%.

These gains marked a shift for the Latino electorate, once perceived as shoo-in votes for Democrats. The vibrant and influential voting bloc’s potential to sway elections in either direction is recognized and reflected in recent polls: While Harris leads with Latino voters, Democrats now face their lowest level of support from Latinos in the last four presidential election cycles.

Harris must make up lost ground in swing states like Pennsylvania as the campaign cycle reaches an apex. Moving the needle even a single point may be crucial to a win, and both parties are angling to sway voters who have yet to make up their minds—and turn out the ones who have.

Historically, drawing younger Latino voters to the polls has been challenging. Latino civil rights and advocacy group UnidosUS projects that 1 in 5 Latinos who vote in November will be young adults casting their ballot for the first time. This voting group is “significantly” more likely to identify as independent than the overall electorate, according to UnidosUS, signaling that a cohort of young voters may be open to the messaging of either candidate.

“There are still individuals that are undecided, and rightly so,” Restrepo said. “Issues that matter to these individuals are issues related to the economy first and foremost, and reproductive rights.”

Stacker

On the economy and reproductive rights, parties are vying to give Latino voters a home

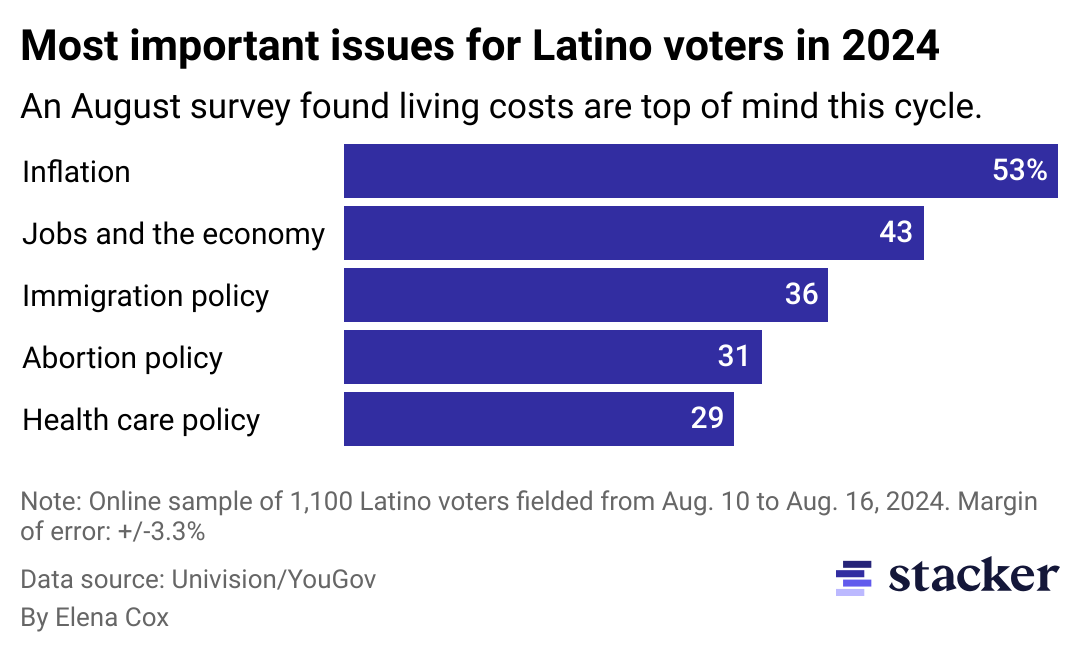

Bar chart showing most important issues for Latino voters in 2024, including inflation, jobs and economy, immigration, abortion, and health care.

Along with immigration and health care, reproductive rights and the economy top the key issues for Hispanic voters, according to an August poll by Univision and YouGov. And as costs rise, housing affordability has also taken center stage.

“A big pride point for Latinos is the fact that they were able to own their own home,” Restrepo said.

In the last four years, homeownership has become an increasingly elusive piece of the American dream, as higher interest rates and record housing prices have kept homeownership out of reach for many working Americans. Spurred by a real estate boom during the COVID-19 pandemic, home prices in some parts of heavily Latino southeastern Pennsylvania nearly doubled in the last five years. In Joe Biden’s hometown of Scranton, median prices reached $193,000 in August 2024.

“For individuals that might have come here in the last 10, 15 years, established ties to the economy, and are thinking of moving from an apartment or rental house to their own house, they’re finding it very difficult to make that upgrade,” Christopher Borick, a political science professor and director of the Muhlenberg College Institute of Public Opinion in Pennsylvania, told Stacker.

Both candidates have addressed the issue of housing affordability. Trump has said he would get rid of restrictive zoning regulations to build new homes but has also argued that his plan for the mass deportation of immigrants living in the country illegally will free up housing. Harris, on the other hand, has promised to build 3 million more homes, give first-time homebuyers tens of thousands toward their purchase, and crack down on landlords’ algorithmic rent-setting practices.

Meanwhile, voters are also feeling the crush of surging rental costs, according to Nancy Herrera, Arizona state program director at Poder Latinx, a nonpartisan civic engagement organization that holds events for the Latino community in six states. In the Phoenix area, where 1 in 3 residents identify as Hispanic, rents have skyrocketed 30% since 2020.

Among some segments of the Latino electorate, concerns about housing may be eclipsed by the urgency of reproductive rights—particularly in states like Pennsylvania and Arizona, where reproductive rights are restricted.

In Arizona, where an estimated 1.3 million Latinos are eligible voters, the electorate will decide whether to pass ballot Proposition 139 to amend the state constitution, guaranteeing a fundamental right to abortion care. In the Grand Canyon State, Latinas of childbearing age make up a far greater portion of the electorate than white women, according to the UCLA Latino Policy & Politics Institute.

Reproductive rights are a centerpiece of the Democratic campaign strategy as the party lambastes Trump for appointing the judges who overturned the Supreme Court decision protecting abortion care. Trump, meanwhile, recently said he would veto a federal abortion ban. Herrera calls it a “tricky” subject to discuss among a portion of the larger Latino community, which tends to be more religious. Still, she said a generational divide on abortion may be shifting. A September poll from The Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research found most Hispanic Americans support abortion access in some form.

“[More] older Latino folks are understanding reproductive justice and understanding why we’re fighting for it,” Herrera told Stacker.

Canva

Realizing the turnout

Two lines of people wait to sign up to vote.

Whether a wave of Latino voters materializes will depend heavily on the outcome of dueling campaign efforts, like the ones in Pennsylvania, as well as the impact of nonpartisan groups like Poder Latinx encouraging turnout and helping to eliminate barriers to voting.

Poder Latinx’s team of 40 canvassers provides educational resources to Latinos in the battleground state of Arizona. The organization reaches people who work long hours and lack time to educate themselves on candidates’ policies, as well as those who may not understand voter registration or ballot information that shows up in the mail, according to Herrera.

Previous studies have shown that young Latinos nationwide, who make up the largest portion of the Latino electorate, face barriers to participating in elections and vote at the lowest rates of any demographic. They often lack interest, time, and knowledge of voter registration, and they’re less likely to receive outreach.

As a longtime Pennsylvania resident who grew up in Scranton, Borick has studied the shifting demographics and political landscape. Low turnout relative to the broader electorate has typically mitigated the political potency of Latino voters, leading to their characterization as a “sleeping giant” or an “unrealized demographic” that could exert its will on electoral politics at any time, Borick said.

Half of Latinos of all ages polled by UnidosUS said that neither campaign nor political party had reached out to them about the coming election. In just the last few months, campaigns have scrambled to boost outreach in key swing states like Nevada, Wisconsin, North Carolina, and Georgia. The success of those efforts could have an outsized impact on the next four years.

From his vantage point in Pennsylvania, Borick is inundated with campaign mail and finds it hard to believe so many Latinos aren’t seeing the same. The campaigns are “loaded with money” and “talking a big game” about voter mobilization within the Hispanic community, according to the professor.

“Just how deep it is and how successful it’s been is uncertain at this point,” he said.

Story editing by Alizah Salario. Additional editing by Nicole Caldwell. Copy editing by Tim Bruns.