The debt ceiling has existed since 1917. Here’s how it’s impacted government spending ever since

Joshua Roberts // Getty Images

The debt ceiling has existed since 1917. Here’s how it’s impacted government spending ever since

The Constitution gives Congress the power to borrow money on the United States’ credit and it has imposed a cap or ceiling on how much debt the Treasury can assume to pay for programs already approved. In the past, congressional votes to increase borrowing was a bipartisan affair, but in today’s highly partisan atmosphere, battles over the debt ceiling have brought the country to the brink of default.

By 2012, Republicans had raised the debt ceiling 54 times, and Democrats had upped it 40 times, according to an analysis by the Guardian. Ronald Reagan boosted the debt ceiling 18 times, and Jimmy Carter and Lyndon Johnson each raised it 10 times.

Economists warn of severe consequences if the United States does not resolve a debt ceiling crisis. Stock prices could tumble, interest rates could soar, and the country’s financial reputation could end in tatters. Domestic programs such as Medicare could be in jeopardy.

Stacker compiled a list of 10 key moments defining how the country’s debt ceiling affects its spending by reviewing news articles, government reports, and academic papers. Here is a look at how we got to where we are and how the crisis might be eased.

![]()

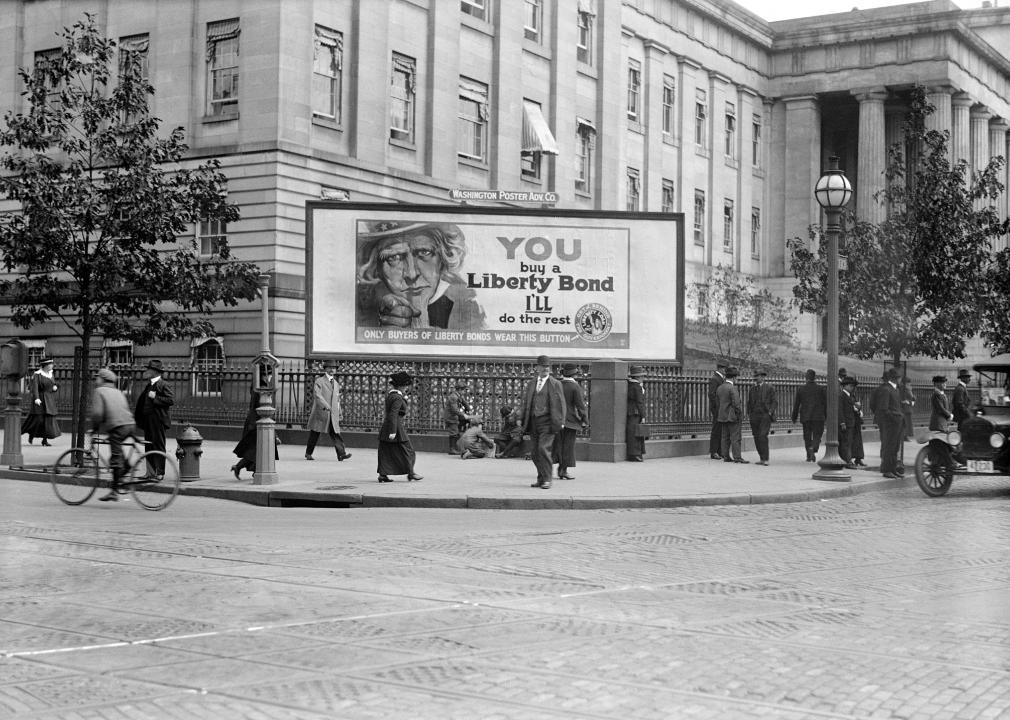

Universal History Archive // Getty Images

When was the debt ceiling imposed?

Before 1917, Congress permitted the U.S. Treasury to borrow for specific programs, with each loan needing Congressional authorization in separate legislation. But when the country entered World War I, Congress began to allow the Treasury to sell war bonds, aka Liberty Bonds, as needed. The Second Liberty Bond Act of 1917 established a debt ceiling of $11.5 billion. Congress continued to permit the Treasury more latitude during the 1920s and 1930s until imposing an overall limit on federal debt in 1939 of $45 billion. That was about 10% above the total debt, according to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

Ramin Talaie // Getty Images

How often has the ceiling been changed?

The debt limit has been revised about 100 times since the end of World War II. It increased three-fold in the 1980s, from less than $1 trillion to nearly $3 trillion, then doubled in the next decade, to nearly $6 trillion in the 1990s, according to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. The ceiling doubled again in the 2000s to more than $12 trillion. The Budget Control Act of 2011 increased it by $900 billion and in addition, authorized the president to raise it by another $1.2 trillion. Separately legislators have suspended the ceiling seven times since 2013, and on a few occasions it has gone down.

NIELS CHRISTIAN VILMANN // Getty Images

Who else has a debt ceiling?

Among major Western countries, only Denmark has a ceiling on its debt and it is relatively much higher to its spending. After its debt neared 75% of the ceiling in 2010, the limit was more than doubled, the Council on Foreign Relations noted. Denmark put the limit in place in the 1990s when it delegated the country’s finances to its central bank. Unlike the U.S., Denmark does not let political drama interfere.

Wally McNamee // Getty Images

President Reagan campaigns against the federal debt

When Ronald Reagan ran for president in 1980, he blasted the size of the federal debt, then about $1 trillion. “So-called temporary increases or extensions in the debt ceiling have been allowed 21 times in these 10 years, and now I’ve been forced to ask for another increase in the debt ceiling or the government will be unable to function past the middle of February,” he said in a speech in February 1981 after taking office. “And I’ve only been here 16 days.” But far from falling, the national debt tripled over the decade to $3 trillion, and President Reagan ended up raising the ceiling 18 times. He blamed Congress.

Consolidated News Pictures // Getty Images

Speaker Gingrich upends Washington

Georgia’s Newt Gingrich became speaker of the House in 1994 when Republicans gained the majority, and the fiscal conservative zeroed in on trying to enact the deep budget cuts he favored. He refused to schedule a vote on increasing the limit until President Clinton agreed to the Republicans’ balanced budget. The result? A partial government shutdown that roiled the country over 21 days at the end of 1995 and the beginning of 1996, until the GOP gave way in the face of public opposition.

The White House // Getty Images

Debt ceiling crisis results in credit rating drop

Republican opposition to the Affordable Care Act led to an impasse over the debt limit in 2011, and spurred Standard & Poor’s to downgrade the U.S. credit rating. President Barack Obama and Congress came together on the Budget Control Act of 2011, which boosted the debt ceiling by $900 billion and authorized the president to raise it by another $1.2 trillion.

The Washington Post // Getty Images

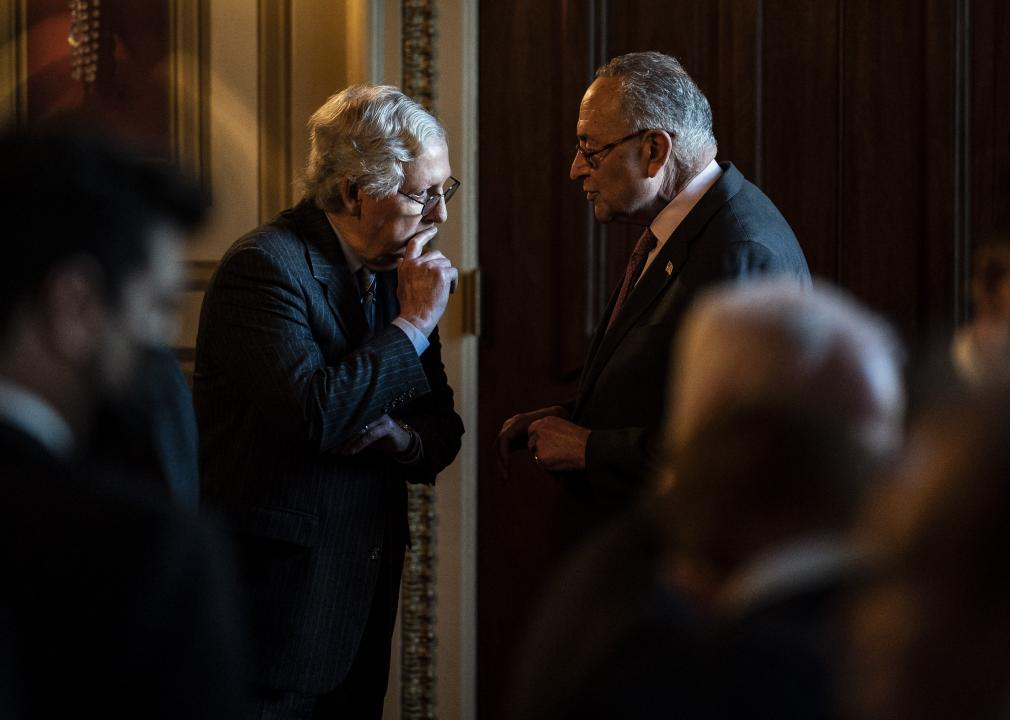

Senator Mitch McConnell proposes reform

In 2011, Sen. Mitch McConnell, the Kentucky Republican who at the time was the Senate minority leader, proposed that the president be responsible for raising the cap subject to congressional review. Congress could block any increase with a joint resolution. There is no suggestion that he would support such a plan now, CBNC notes. In the current standoff, Senator McConnell insisted Democrats raise the debt limit on their own without GOP help, then in November 2021 began discussions with Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer about heading off a government shutdown in December.

Bill Clark // Getty Images

Crisis averted when ceiling suspended

During the debt ceiling crisis of 2013, the limit was suspended for a time and the Treasury took what is known as extraordinary measures, which typically include suspending new investments or payments to federal employees’ retirement accounts. The Government Accounting Office found there was nevertheless a cost to taxpayers. As the date neared when the Treasury would have no other options, some investors eschewed Treasury securities, worried they would not be paid on time. Others insisted on a greater return for the risk they faced.

Tom Williams // Getty Images

Suspending the debt ceiling for two years

The debt ceiling was suspended until July 31, 2021, under the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019. The ceiling stood at $22 trillion when Congress passed the bill and since then the government has borrowed $6.5 trillion as of June 30, 2021. When it was reimposed in August, and the debt had climbed to $28.5 trillion, the Treasury again was faced with taking extraordinary measures to avoid defaulting on its loans. In October 2021, Democrats who control the House temporarily raised the borrowing limit to $28.9 trillion. The vote delayed the deadline for a default only until December 2021.

Alex Wong // Getty Images

Another debt ceiling deadline looms

As the December 2021 deadline approaches for another debt ceiling crisis, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer of New York and the Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky held discussions on how to avert a default. The Treasury Department warned of a Dec. 15 deadline, after which it will be unable to meet its financial obligations. Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia suggested there may be a way to pass legislation with a simple majority instead of the 60 votes usually required. Meanwhile Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said she supports discarding the borrowing limit as it’s currently structured. Proposals that were introduced in Congress include appealing the limit outright or transferring authority over the borrowing limit to the Treasury Department.