Reports of hate crimes are rising—here are how protections vary by state

SETH HERALD/AFP via Getty Images

Reports of hate crimes are rising—here are how protections vary by state

A ‘Stop Hate’ sign is held at a rally in Detroit

One of the most pressing issues in America today is the increase in hate crimes—those that are motivated by prejudice against someone’s race, sexual orientation, religion, gender, national origin, or other factors. In 2020, there were more than 8,000 hate crimes committed in the U.S., up from just over 7,000 the year before. The greatest percentage of hate crimes were motivated by race, ethnicity, and ancestry, according to the FBI. Stigmatizing rhetoric around the COVID-19 pandemic and the monkeypox outbreak have only fueled the violence.

Legislators have been trying to curtail these types of crimes since at least as far back as 1968, when the first federal hate crime legislation was passed with Title I of the Civil Rights Act. Some states have also enacted their own, often more stringent, hate crime legislation. In fact, there are currently 46 states with some type of hate crime law on the books. But those laws differ, sometimes substantially, by state.

Stacker collected information and statistics from the Movement Advancement Project’s Policy Spotlight: Hate Crime Laws report to understand how hate crime laws differ across the U.S.

You may also like: 20 influential Indigenous Americans you might not know about

![]()

Matt Albasi // Stacker

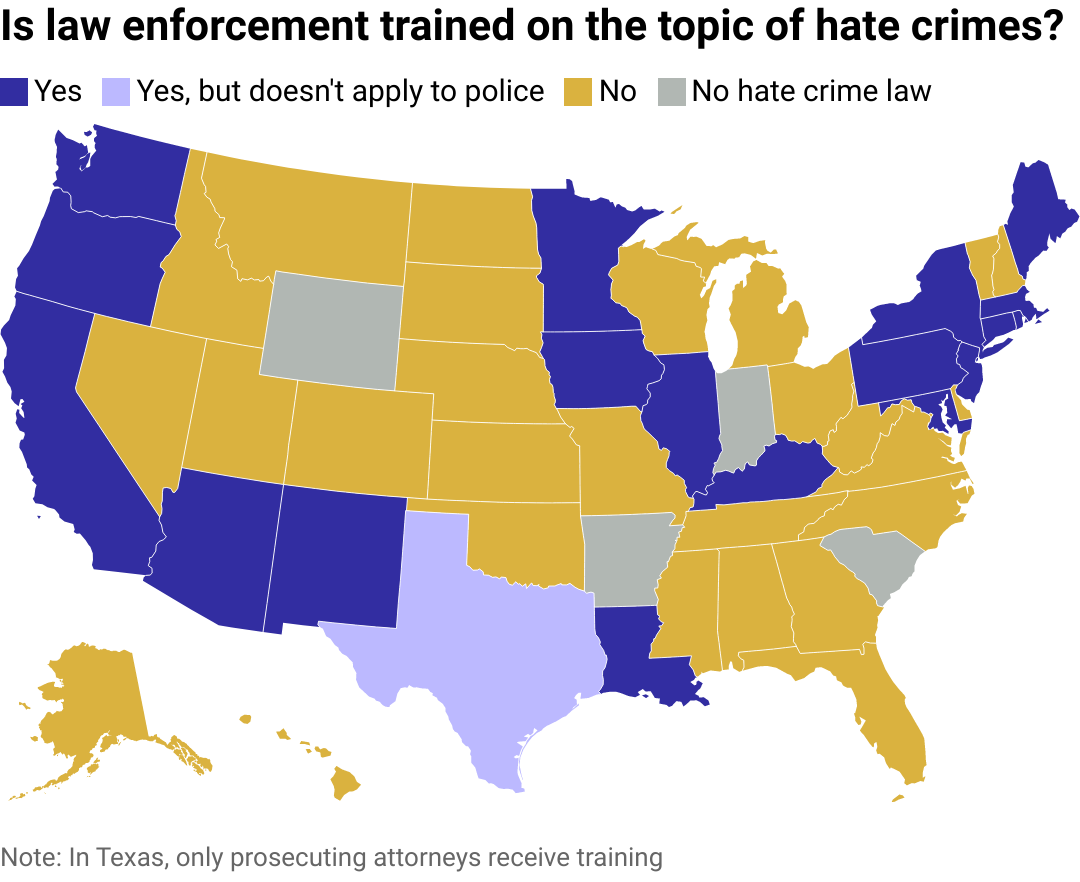

Law enforcement training

A map of the U.S. showing which states train law enforcement on the topic of hate crimes

– Number of states with provisions: 18

Law enforcement plays an essential role in preventing hate crimes. The police and other relevant law enforcement bodies are expected to protect the lives and property of all members of society regardless of their ethnicity, social status, or sexuality. In many states, law enforcement bodies have taken steps toward curtailing the incidence rate of hate crimes.

According to the MAP report, 18 states have made it a requirement for law enforcement officers to receive basic training on the identification of hate crimes, the proper response to them, and data collection and reporting. To properly combat hate crimes, law enforcement officers and others working to protect people from hate crimes need accurate data that can be used to understand and allocate resources effectively.

However, the report also notes that some members of vulnerable communities (people of color, LGBTQ+ folks, etc.) who survive hate crimes may be hesitant to report them to the police due to biases in the criminal justice system.

Matt Albasi // Stacker

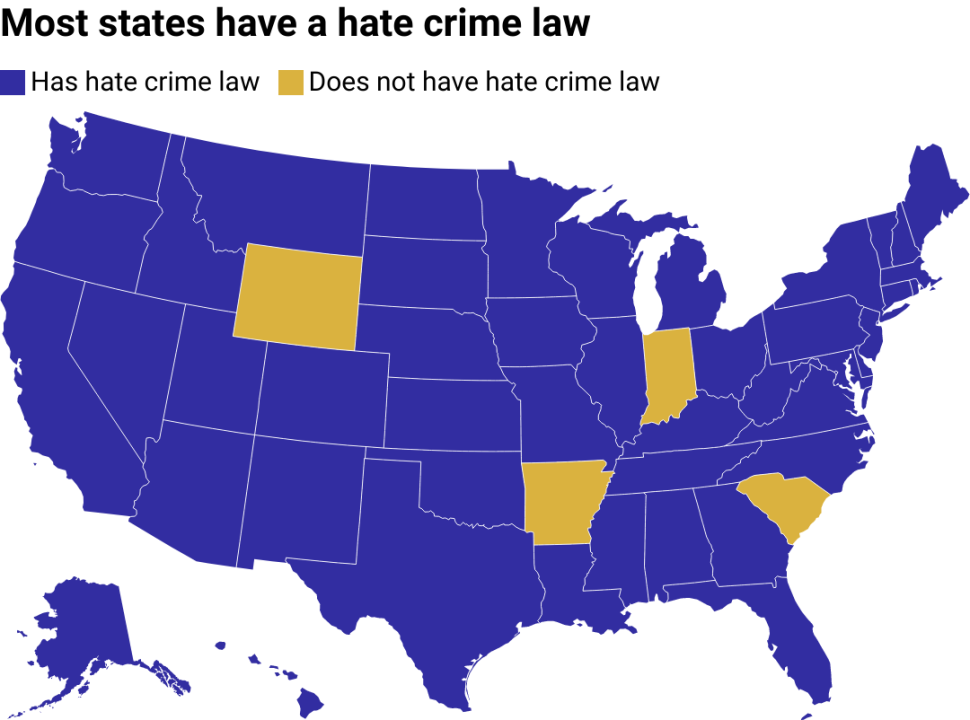

Criminal punishment

A map of the U.S. showing which states have hate crime laws

– Number of states with provisions: All states with hate crime laws (46 states plus Washington D.C.)

Another practical approach to hate crime prevention is through criminal punishment—one tool that is at the heart of each state’s hate crime prevention laws. By making prison sentences longer, states hope to deter people from committing these crimes.

All states with hate crime laws have adopted some form of enhanced sentencing as a supporting measure to ensure that such crimes are discouraged in every possible way; however, there is not sufficient evidence to prove that criminal punishment significantly reduces crime. Even so, sentence enhancements may show lawmakers’ commitment to preventing hate crimes.

Matt Albasi // Stacker

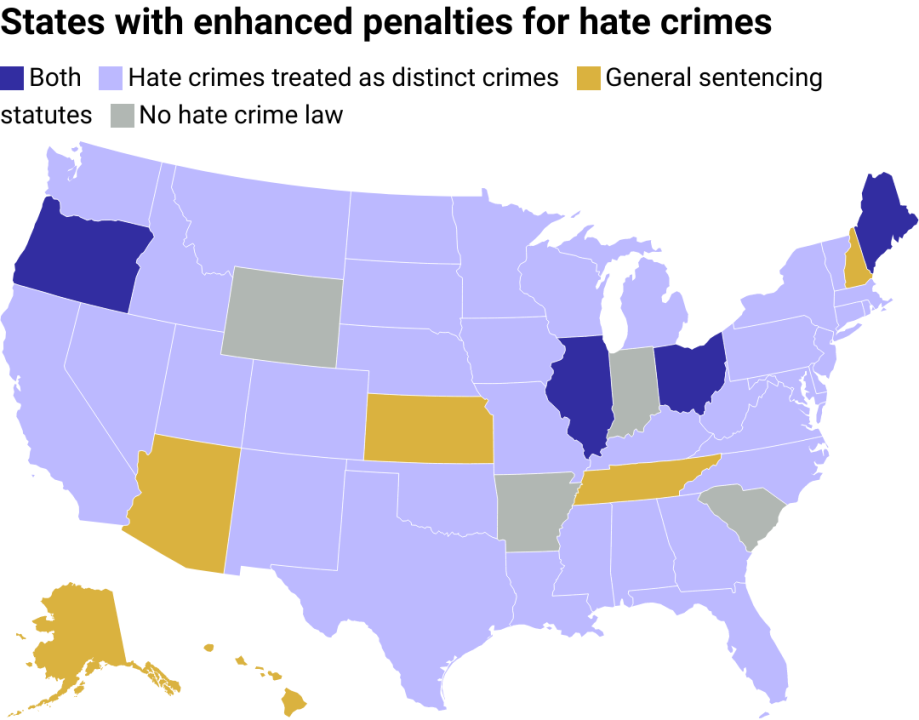

Distinct crime vs. general sentencing statutes

A map of the U.S. showing which states use distinct crimes, general sentencing, or neither to prosecute hate crimes

– Number of states with provisions: 36 (plus D.C.) with distinct crime, 6 with general sentencing, 4 with both

Enhanced penalties are enacted in two primary ways: by treating hate crimes as separate, distinct crimes (on top of the regular criminal charges filed in a case), and through general sentencing statutes that identify the underlying, hate-related characteristics of a crime. When treated as a distinct crime, the crime is defined, protected classes are specifically listed, and penalties are established. In cases of general sentencing, statutes require that selecting a target from protected classes should be considered an aggravating factor, which in turn leads to harsher punishment during sentencing.

For example, a person residing in a state that treats hate crimes as distinct could face two charges for one assault—one for the assault itself, and one for a hate crime; however, under general sentencing statutes, a person would be charged for assault only but receive a harsher punishment if eventually convicted. Currently, there are 36 states that treat hate crimes as distinct crimes, six states with general sentencing statutes, and four states with both.

CHOONGKY // Shutterstock

Protected classes

Demonstrators march across Brooklyn Bridge at Stop Asian Hate rally

– Number of states with provisions: All states with hate crime laws, but specifics vary

Hate Crime laws are established to protect certain classes of people. To effectively achieve that goal, these laws usually list certain classes of people with specific traits or identities (disability, gender, or race, for example) as people that are protected by the law.

The categories of people protected by these laws usually mirror the categories listed in the federal civil rights law; however, in some states, the classes of protected people can vary. So overall, all states with hate crime statutes have some protected classes, but those classes can vary and generally help define what is considered a hate crime in a particular state.

Matt Albasi // Stacker

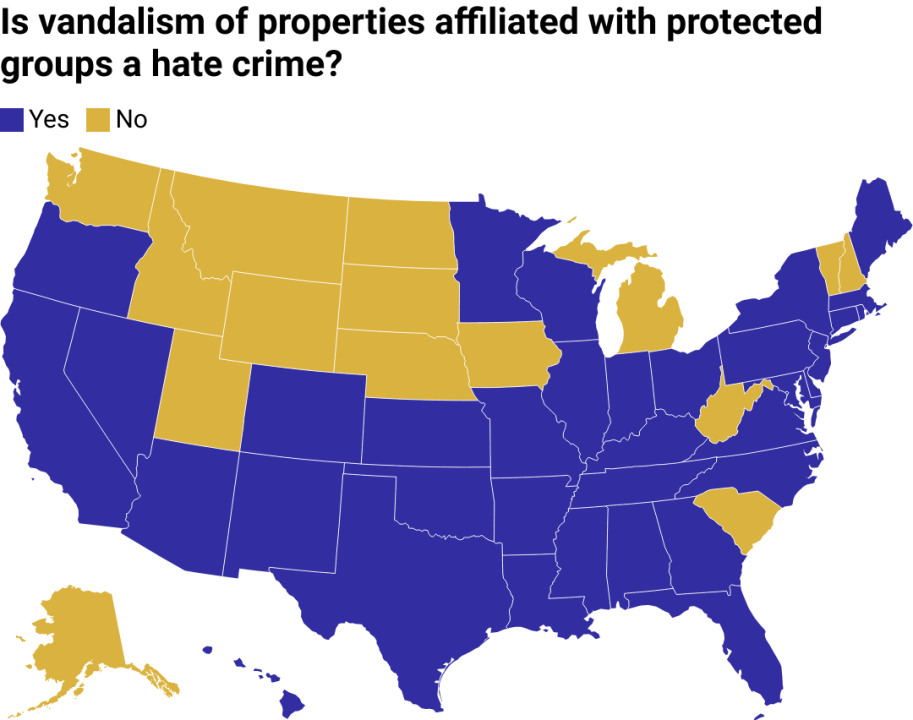

Provisions against hate-based vandalism to institutions

A map of the U.S. showing which states have protections against vandalism of property of protected classes

– Number of states with provisions: 35 and Washington D.C.

In some instances, hate crimes are not targeted against individuals alone. Sometimes they’re committed against the property owned by people within a protected class, which is known as institutional vandalism. These might include Black-owned businesses, LGBTQ+ spaces such as a community center, or a religious institution such as a church or synagogue. The need for protections against such acts is where institutional vandalism statutes come into play.

These statutes consider the businesses and gathering spaces of people in protected classes as assets to be protected. So far, 35 states and Washington D.C. have institutional vandalism statutes in some form or other. In some states, institutional vandalism is included under the hate crimes umbrella and can be punishable as a hate crime under the law.

You may also like: How driving is subsidized in America

Matt Albasi // Stacker

Collateral consequences

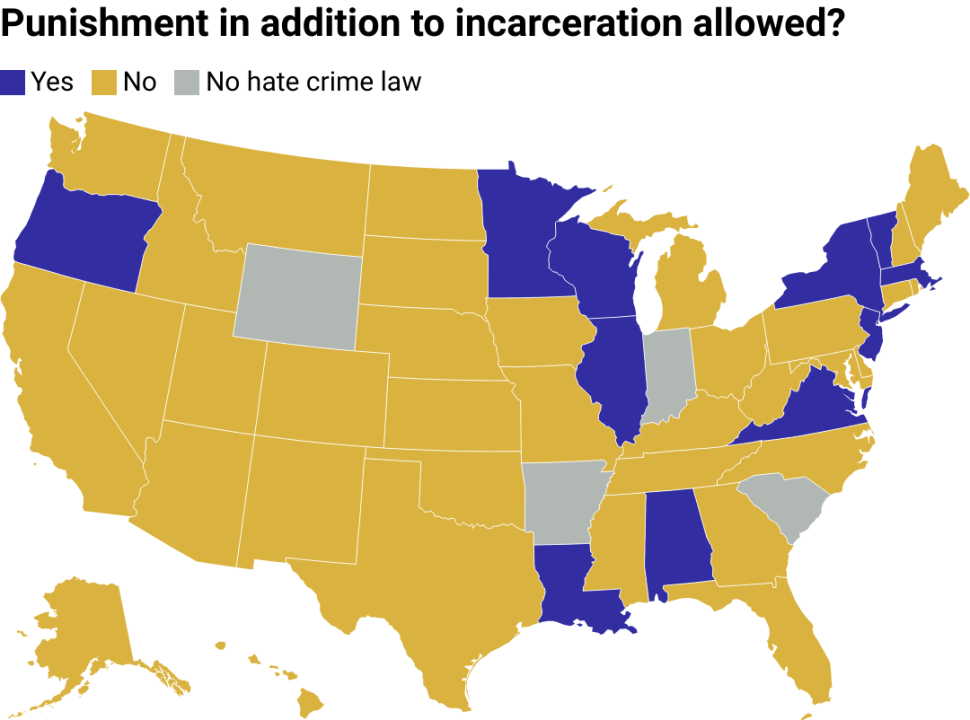

A map of the U.S. showing which states have additional consequences beyond incarceration for hate crimes

– Number of states with provisions: 11

While most states use incarceration as punishment for hate crimes, some states employ additional consequences as well. These additional consequences are included alongside incarceration. For instance, in three states, people convicted of a hate crime are prohibited from owning a firearm. In four states, a hate crime conviction can result in disqualification from some forms of employment.

These additional consequences allow a controlled level of discretion in the sentencing of people convicted of hate crimes. The provisions do not replace existing laws, but can increase their effectiveness.

Matt Albasi // Stacker

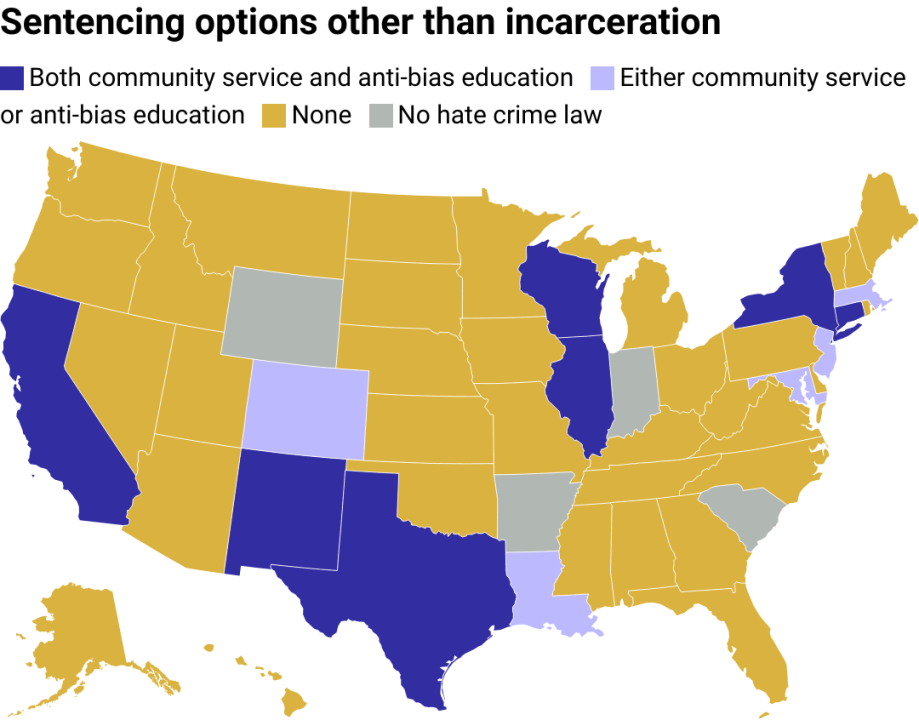

Sentencing options other than incarceration

A map of the U.S. showing which states have additional sentencing options beyond incarceration

– Number of states with provisions: 12

As an alternative to enhanced penalties, some states allow courts to exercise their discretion in choosing from available sentencing options. A few states’ hate crime laws explicitly allow courts to recommend or require those convicted of hate crimes to complete community service or anti-bias education instead of or in addition to a prison sentence.

Laws like this allow some states to explore alternative punishments, rather than relying solely on traditional ones like incarceration. Alternative consequences may include completing community service or working with victim support services which can help bridge the gap in understanding that could lead to a hate crime in the first place.

Matt Albasi // Stacker

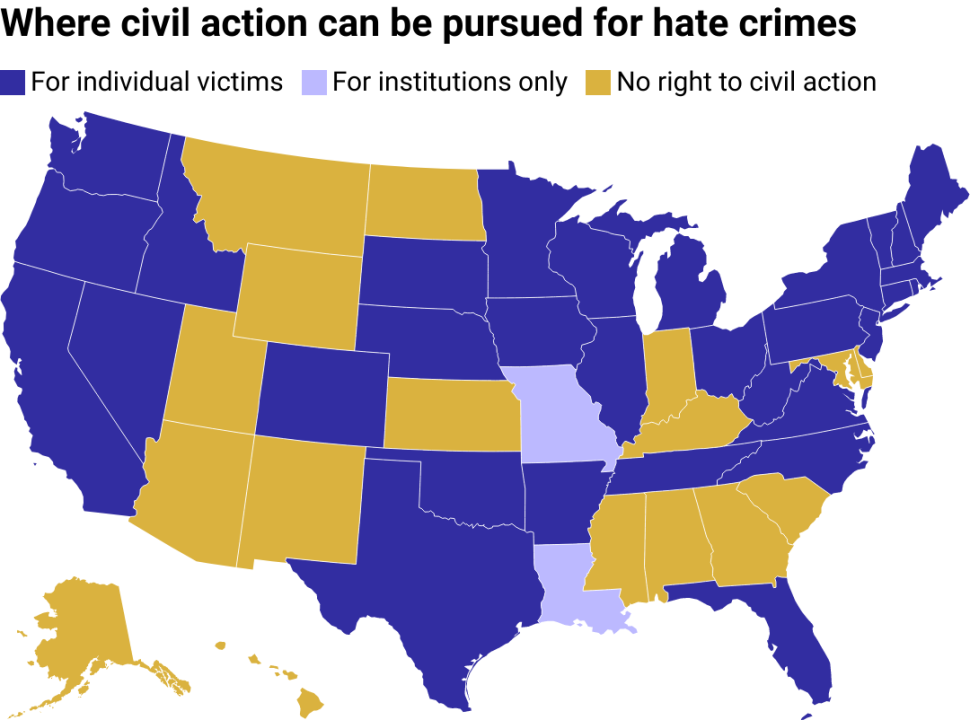

Right to civil action exists for individuals who experience hate crimes

A map of the U.S. showing which states allow victims of hate crimes to pursue civil action

– Number of states with provisions: 31 and Washington D.C.

There are 31 states so far that allow civil action to be brought against people who commit hate crimes—separate from criminal proceedings. In these states, victims of hate crimes can sue for damages, financial compensation, or injunctive relief such as orders of protection. In at least 12 states, the attorney general may also pursue civil cases for survivors of hate crimes. Some states also retain the right to pursue criminal charges without the consent of the victim or survivor. Notably, in Arkansas, which has no hate crime laws on the books, survivors of certain hate-motivated crimes can still pursue civil action.

Matt Albasi // Stacker

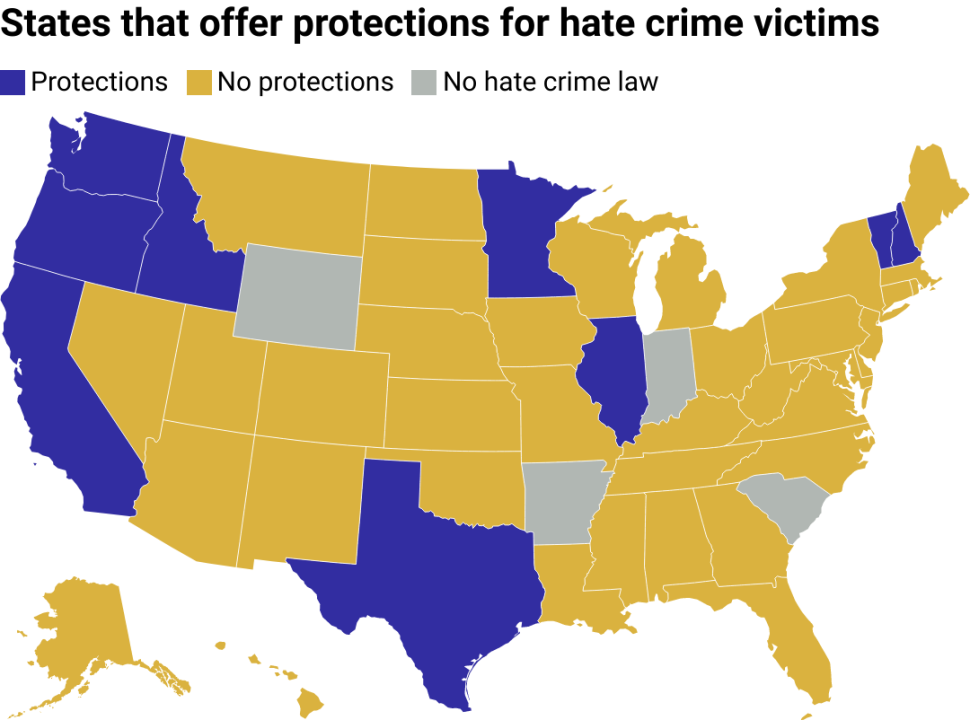

Support or protections for survivors of hate crimes

A map of the U.S. showing which states offer protections or support for victims of hate crimes

– Number of states with provisions: 9

Hate crimes can change victims’ lives in an instant. Out of the states with existing hate crime laws, only nine states offer statutory protections for victims. These protections usually include restraining orders granted, even before the suspected individual is convicted. Two states even go as far as establishing statutes that direct victims to community support services where they can receive additional support and remain safe. Some states also have provisions that protect a hate crime survivor or witness from being detained by law enforcement for a potential immigration violation.

Matt Albasi // Stacker

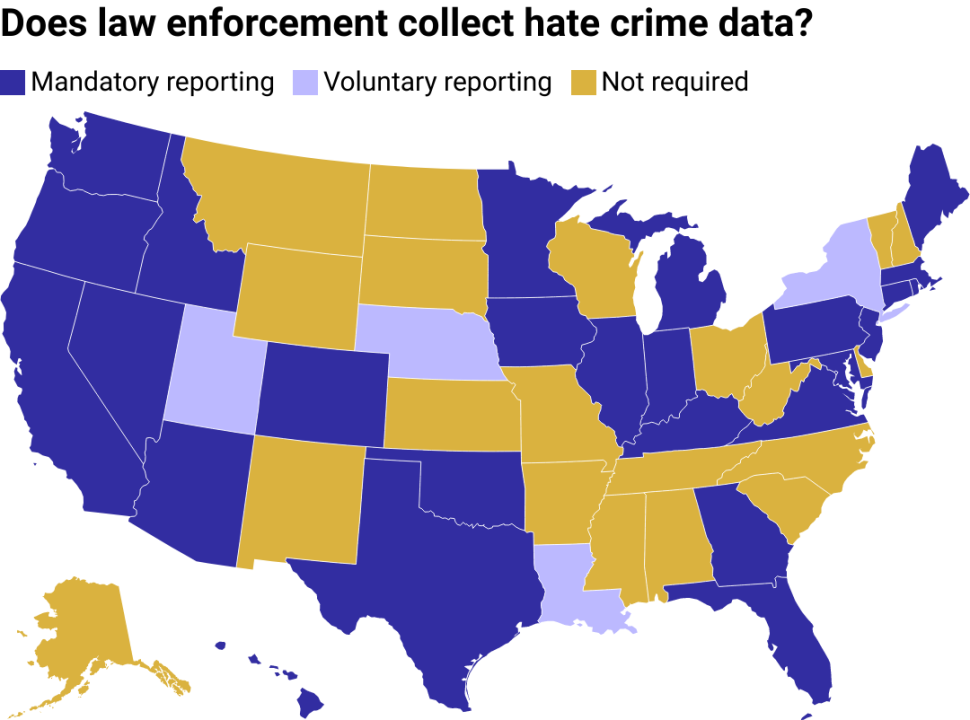

Requirements to collect data on hate crimes

A map of the U.S. showing which states require law enforcement to collect and report data on hate crimes

– Number of states with provisions: 30 and Washington D.C.

A considerable number of hate crimes go unpunished because of a lack of proper reporting standards. As it stands, 26 states have laws requiring law enforcement to report hate crimes to a central state repository, while another four states and D.C. require states to collect data but only through voluntary law enforcement reporting.

These states also publish annual reports on patterns and the nature of crimes committed. Only New Mexico has laws requiring law enforcement to report hate crimes to the FBI directly, though the state has no other requirement to collect hate crime data. With 20 states not requiring data collection, many hate crimes are never documented.

You may also like: How cellphone use while driving has changed in America in the last 20 years