New film tracks animal migrations in and out of Grand Teton

MOOSE, Wyo. (KIFI) – A new wildlife documentary chronicling the large mammal migrations of Grand Teton National Park was released online this week, showing how the park is biologically connected to distant habitats in Idaho and Wyoming.

Animal Trails: Rediscovering Grand Teton Migrations is now available for streaming, after screening in Grand Teton National Park’s Craig Thomas Discovery and Visitor Center and Colter Bay Museum during the summer of 2023. You can watch the film on Vimeo here: vimeo.com/migrationinitiative/AnimalTrails.

The film documents more than a decade of research revealing how Grand Teton National Park’s mule deer and pronghorn actually depend on habitats up to 190 miles away from the park boundaries.

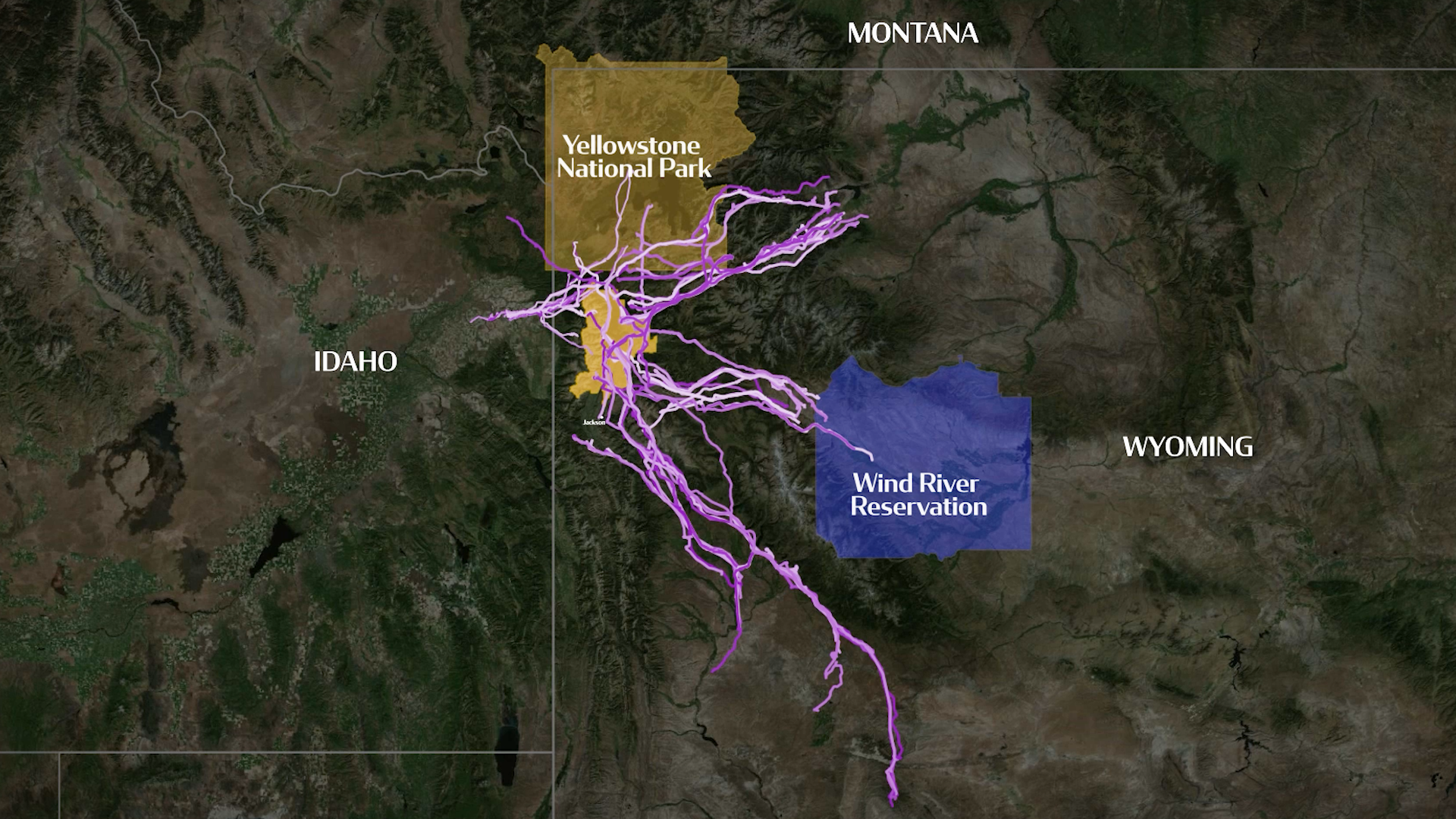

Many of the wild animals that visitors enjoy in Grand Teton spend only part of the year there. Winter ranges and migration routes across Idaho, Wyoming, and the Wind River Indian Reservation are vital for the survival of big game herds in the national park.

“We are living amid a revolution in migration science happening in and around the edges of one of America’s crown-jewel national parks,” said director Gregory Nickerson, a writer and filmmaker with the Wyoming Migration Initiative at the University of Wyoming. “Grand Teton migrations are a story of diverse land ownership, and stewardship of migrations on this landscape over thousands of years.”

Animal Trails was co-produced by the Wyoming Migration Initiative and Grand Teton National Park. The film is part of a new migration-themed exhibit Grand Migrations: Wildlife on the Move that recently opened at the park’s Craig Thomas Visitor Center in Moose, WY. Both the film and exhibit reflect a growing emphasis by Grand Teton National Park managers to tell the story of wildlife migrations and the regional partnerships needed to conserve them.

“Millions of visitors come from all over the world to see the magnificent wildlife that calls Grand Teton National Park home,” said Chip Jenkins, superintendent of Grand Teton National Park. “To have the chance to see thousands of elk migrate, like they have done for centuries, is awe-inspiring and you know you are witnessing something vital to their survival.”

Grand Teton National Park has made a dedicated effort to map mule deer migrations since 2013, complementing parallel efforts by the University of Wyoming, Idaho Fish and Game, Wyoming Game and Fish Department, and the Shoshone and Arapaho Tribes Fish and Game of the Wind River Indian Reservation.

“When we place a collar on a mule deer we never know where it’s going to end up,” said Sarah Dewey, wildlife biologist with Grand Teton National Park. “It’s been exciting to discover migratory connections to winter ranges far beyond the boundaries of the park, across the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.”

Migration science in the Tetons

Grand Teton National Park migrations arise from the fact that the area is one of the wettest parts of the middle Rocky Mountains, attracting migrating animals from great distances. While the warm seasons are verdant, winters are harsh along the Tetons, especially in the northern part of Jackson Hole. In response, animals migrate to winter ranges with less snow.

Elk migrations have long been recognized by Indigenous hunters, ranchers, outfitters, and biologists in Jackson Hole. During the 1930s, the Wyoming Game and Fish Department mapped movements of elk in detail by counting tracks in the snow.

Around the turn of the 21st century, biologists deployed GPS tracking collars to map pronghorn and mule deer migrations. Detailed maps of these movements are redefining how people understand the ecology and geography of the Grand Teton area, and across vast stretches of the Rocky Mountains.

Animations in the film show how mule deer make some of the most impressive migrations among ungulates, or hooved mammals. Some mule deer depart Grand Teton National Park to migrate west over the 9,000-foot passes into Idaho, where they spend winter along the Teton River Canyon and the wheat fields of the Teton Valley.

However, the majority of mule deer stay in Wyoming and migrate east across rugged mountain passes to the Shoshone River near Cody, the Wind River Indian Reservation, or the Green River Basin.

A long history of migrations

The film foregrounds the fact that Indigenous people have known about migrations for a long time and woven their lives into these animal movements both in the past and in present day.

Shoshone educator George Abeyta opens and closes the film with “Thanks to migrations, the Grand Teton area has been rich in sustenance for all time,” Abeyta says. “We need to listen to what our animals are telling us.”

Maps of the migrations underscore how a significant part of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem centers on migrations to Grand Teton National Park. More than a century of conservation has sustained these animal movements across national parks, national forests, Bureau of Land Management sites, and vast working lands (private ranches) that are a hallmark of the “Cowboy State.”

And yet, the biologists in the film recognize growing threats to Grand Teton migrations due to rural development, increased traffic, outdated fence designs, loss of working ranchlands, other private lands and more.

In response, people have joined together to conserve migrations and open spaces through public-private partnerships that cross jurisdictional boundaries.

“While the mule deer movements themselves are spectacular, and delineating them is important, the connections with new partners and collaborators – private landowners and other agencies, organizations, or land managers who are stewards of the winter ranges — are key to conserving well beyond park boundaries and are critical to sustaining these migratory populations with Grand Teton,” Dewey said.

In the film, Wyoming Game and Fish Big Game Migration Coordinator Jill Randall emphasizes the decades of collaborative efforts across the region on wildlife-friendly fence modifications and wildlife crossings.

Clen Atchley, Tony Mong, Jill Randall, and Max Ludington

In addition, motorists can take action to conserve migrations. For many animals, spring and fall migrations are times when animals may be more active near roadways and can cross the roads unexpectedly. Drivers should use caution and slow down, especially at dawn, dusk, and during the night when visibility is reduced. Being aware of your surroundings and paying keen attention helps reduce the number of large animals hit by vehicles every year.

Often migrations are anchored by private lands stewarded by ranchers and farmers, many of whom voluntarily place their lands in conservation easements. Some of these very landowners helped create nonprofits like the Jackson Hole Land Trust, the Wyoming Stockgrowers Land Trust, The Nature Conservancy, Teton Valley Land Trust and others.

“Migrations are at the core of how this ecosystem operates, and humans are an integral and enduring part of that story,” Nickerson said. “We hope people watching this film feel inspired and empowered to maintain these incredible migrations long into the future.”

About the film

The Wyoming Migration Initiative production team included associate directors Emily Reed and Patrick Rodgers, and lead scientist Matthew Kauffman.

Seventeen wildlife cinematographers contributed footage to the film, which was funded by the Knobloch Family Foundation, Grand Teton National Park Association, and the George B. Storer Foundation.

Grand Teton National Park mule deer research was funded by Charles Engelhard Foundation, Cross Charitable Foundation, Grand Teton National Park Foundation, Greater Yellowstone Coordinating Committee, Hamill Family Foundation, Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Knobloch Family Foundation, Meg and Bert Raynes Wildlife Fund, pH Fund of Schwab Charitable, Snake River Chapter of the Mule Deer Foundation, and the National Park Service.

The film has a runtime of 25 minutes and will screen at the Grand Teton National Park Craig Thomas Discovery and Visitor Center and Colter Bay Museum during the summer 2024 season. Watch the film on Vimeo here vimeo.com/migrationinitiative/AnimalTrails.