Do health policies keep exclusive breastfeeding out of reach?

Canva

Do health policies keep exclusive breastfeeding out of reach?

A mother breastfeeds a baby.

New parents who choose to breastfeed will find plenty of barriers to starting and even more to continuing breastfeeding.

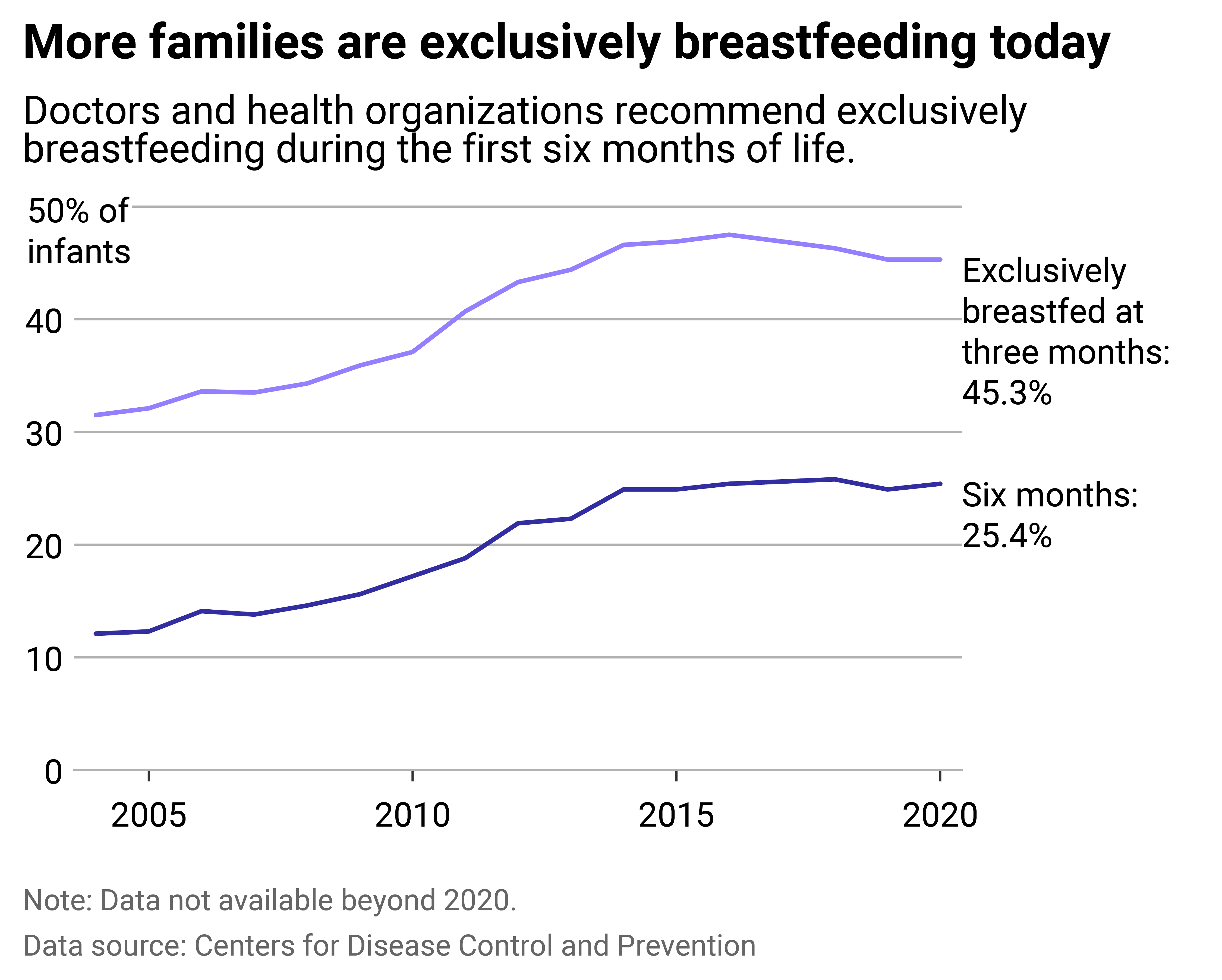

While about 83% of babies have been breastfed at least once in their first month, according to the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data from 2020, parents find it difficult to maintain. By the third month, 45% are exclusively breastfed, down to 25% by their sixth month. Exclusive breastfeeding, meaning an infant receives only breastmilk, requires support. For parents who can and choose to do so, policy can make a significant difference.

Health policy at all levels can make or break the amount of support and resources breastfeeding parents receive. For instance, on the federal level, before the PUMP Act went into effect in April 2023, only some hourly workers at certain employers were required to provide short, unpaid breaks for parents to pump. Because returning to work is one of the main barriers to continued breastfeeding, policy that limits the right to pump at work for nursing parents makes exclusive breastfeeding difficult.

The PUMP Act, which expands the number of hourly working parents eligible for lactation breaks and includes salaried workers, provides more protections—including legal recourse for noncompliance, clear guidance regarding pay during breaks, and lactation space requirements.

Policy at the state level further contributes to breastfeeding’s accessibility issues. Only eight states have relatively generous paid family leave policies, according to a Northwestern Medicine study published in November 2023, which evaluated the generosity of states’ paid family and medical leave policies. There is no national paid parental leave policy and the maximum time a parent can get off is 12 weeks—unpaid.

Considering the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends exclusively breastfeeding infants for 6 months, the lack of paid time off leaves many families unable to do so. How states decide to implement federal programs can also make exclusive breastfeeding recommendations seemingly impossible.

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families provides cash assistance to low-income families, with return-to-work requirements varying across states. In states with strict return-to-work requirements, where all household adults have to go back to work sooner and work a certain number of hours to keep benefits, parents are less likely to continue breastfeeding, according to the Department of Health and Human Services.

Even before leaving the hospital after birth, many families are not set up for success in pursuing long-term breastfeeding plans. Many hospitals don’t prioritize educating new mothers about breastfeeding and don’t provide feeding routines that would support it. In 2007, 24% of birth facilities surveyed by the CDC gave healthy, full-term babies supplemental feeding, which can derail plans to breastfeed.

Northwell Health partnered with Stacker to explore breastfeeding rates with CDC data, highlighting the barriers families face to exclusively breastfeed their children. Read on to learn about major disparities to access, and what states are doing to alleviate them.

![]()

Northwell Health

Barriers to exclusively breastfeeding

Line chart showing more families are exclusively breastfeeding today than 15 years ago. Doctors and health organizations recommend exclusively breastfeeding during the first six months of life. In 2020, 45.3% of infants were exclusively breastfed at three months, while 25.4% of six-month infants were exclusively breastfed.

Some health-related barriers are more difficult to resolve, but in other cases, parents don’t breastfeed due to employment limitations, ambivalence from doctors, embarrassment, limited public spaces to feed, and/or poor social support. For instance, many workplaces don’t have scheduling or private spaces built in to allow parents to pump. For others, breastfeeding can cause physical pain that exacerbates postpartum stress. For still many more, their babies simply can’t latch, or their milk supply is too low.

In some cases, parents want to exclusively breastfeed—but economic and social challenges can make it difficult. This is particularly true for Black people, who breastfeed at lower rates than white and Hispanic mothers. Black women have the highest workforce participation rates of all women and are more likely to be the sole breadwinner of their household. They’re also more likely to be offered formula instead of lactation support at the hospital.

Thankfully, some solutions are being presented.

Doctors, doulas, midwives, and lactation consultants are taking part in state-funded public campaigns aimed at increasing access to education and resources for first-time families. The American Academy of Pediatrics is pushing pediatricians to become health advocates for families who wish to breastfeed, both inside their offices and at the voting booths.

The Affordable Care Act updated its requirements so that insurance plans must cover breastfeeding supplies. And for Black parents, many organizations are undertaking targeted education and awareness campaigns, like Mississippi-based Sharing Health Education Awareness and national Black Breastfeeding Week (Aug. 25-31).

These efforts are producing results, too: Expanded family leave policies, federal assistance programs (including TANF), and workplace policies have helped increase breastfeeding rates. For example, California’s paid leave law, enacted in 2004, has been linked to a 20% increase in rates for breastfeeding in the state.

Story editing by Ashleigh Graf and Kelly Glass. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

This story originally appeared on Northwell Health and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.