15% of youth in the US were treated for mental health disorders in 2021

SeventyFour // Shutterstock

15% of youth in the US were treated for mental health disorders in 2021

Psychologist talking to teenage boy during therapy session.

The kids are not OK. A growing portion of today’s youth are reporting that they struggle with mental health disorders.

It’s a trend exacerbated by the pandemic but one that’s been festering long before the first case of COVID-19 was reported in the U.S. And the latest data tells us only a fraction of those struggling actually receive treatment.

Mental health affects how young people think, perform in school, and interact with the world around them. It can even manifest in physical ways like withdrawal from socialization, getting less sleep, and changes in eating habits.

If left untreated, poor mental health conditions can evolve into disorders or lead to suicide. And treatment is reaching far fewer adolescents who report mental health struggles.

Citing data from the latest National Health Interview Survey from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Sandstone Care examined how youth are receiving treatment for mental health as symptoms of depression among adolescents reach new highs. The CDC only collects data with an option for binary gender selection, which can’t be used to draw conclusions about the mental health treatment of gender-nonconforming and nonbinary individuals.

The typical high school student today is not only navigating the complexities of adolescent hormones, a desire to belong, and stereotypical representations of beauty and success but also new forms of connection made possible by social media, which has been shown to exacerbate poor mental health.

Teenagers, ages 12-17, were more often treated for mental health disorders than younger kids, reaching a rate close to the general adult population.

![]()

Sandstone Care

More youth report mental health concerns than actually receive treatment

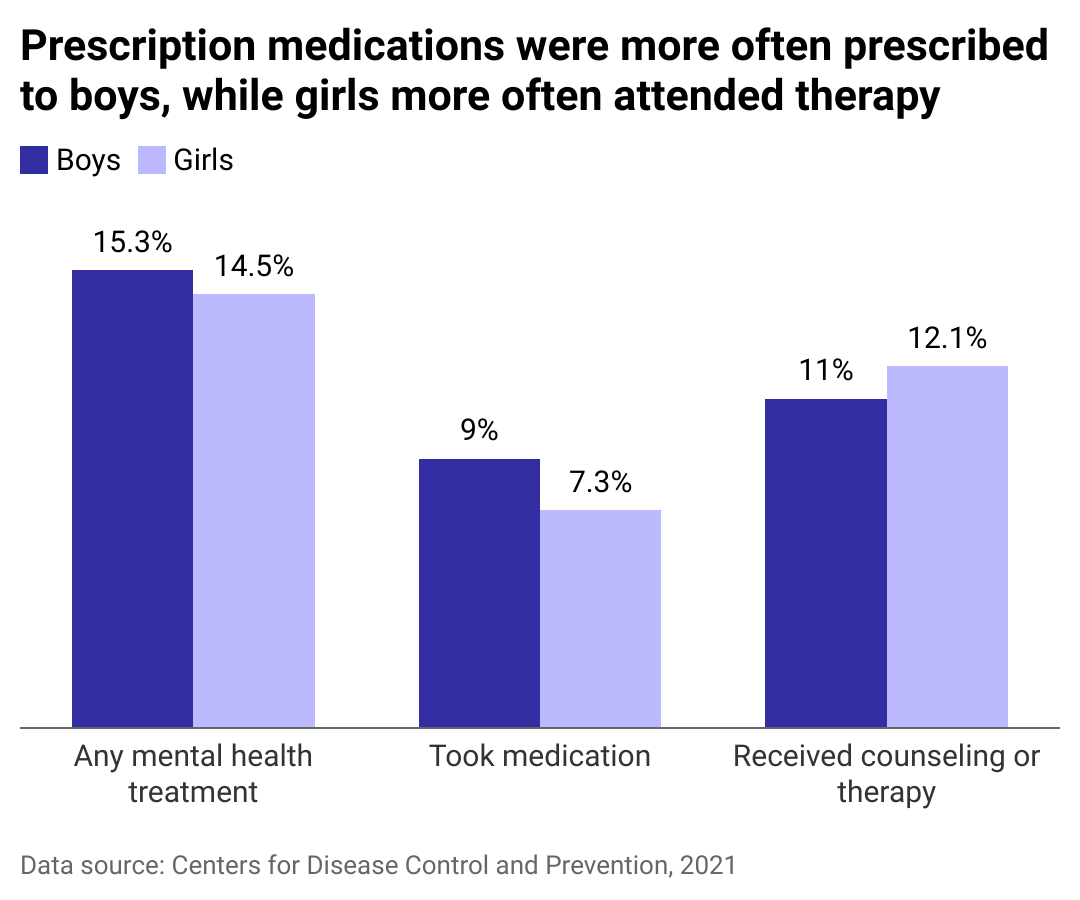

Column chart showing boys were more likely to be prescribed medication for mental health while girls more often attended therapy.

Roughly 30% of high school students reported mental health struggles in 2021, yet just 19% of boys and girls between 12-17 report getting any sort of treatment for their mental health. Recent data on mental health for younger children is unavailable, but 11% reported receiving treatment.

Boys are slightly more likely to take medication, and girl students are slightly more likely than their boy counterparts to get counseling or therapy to assist with their mental health, according to the CDC.

The agency’s data also points to discrepancies among members of various ethnic backgrounds. Asian youth were least likely to have had mental health treatment. White youth were more likely than their Hispanic counterparts to have taken medication as treatment and more likely than Hispanic and Black youth to have accessed counseling.

Data also points to a trend in which adolescents are more likely to have received treatment the more rural their community is. Those in nonmetropolitan regions were most likely to have received treatment of some kind compared with small, medium, or large metro areas.

And while the CDC does not collect data on individuals who identify as neither male nor female, about 3 in 5 LGBTQ+ youth who wanted mental health care in the past year could not get it, according to a recent survey from The Trevor Project.

Most people still feel treated differently because of mental illness

Even in the adult population, Americans voice trouble getting proper mental health treatment, citing the cost of treatment and the stigma of discussing mental illness as barriers to getting the help they need. About 3 in 5 Americans without health insurance reported stopping treatment because it was too costly, according to the survey.

A 2021 National Alliance on Mental Illness survey found that most American adults agree mental illness remains stigmatized, and 3 in 5 adults living with mental illness feel they are treated differently by people who know about their condition. The same barriers and stigmas associated with mental health treatment are passed down to children.

NAMI officials voiced optimism, though, that the COVID-19 pandemic has seemingly stimulated more open discussions about mental health. “The survey points out that once people with mood disorders get care, they do well and can flourish,” NAMI Chief Medical Officer Ken Duckworth, M.D., said in a statement. When left untreated, mental illness can create further problems in life, affecting earning potential, relationships, and other areas of life where people find fulfillment.

Still, barriers remain to accessing treatment as well as getting proper treatment. People from marginalized racial and ethnic groups often avoid or delay treatment, fearing racism in health care and discrimination at work and in their personal lives. The stigma that discourages people from getting mental health treatment, however, is slowly being reduced.

A 2021 study in the JAMA Network Open journal found that Gen Z, the group born between 1997-2012, may carry less prejudice toward mental illness. Researchers found that stigmas associated specifically with depression decreased in younger generations.

Shifting social behaviors behind the youth mental health crisis

More young people in the U.S. are engaging with social media of some sort, a trend sped up over the pandemic. According to the Pew Research Center, YouTube is the most universally used platform with 95% of teenagers aged 13-17 reporting they use it. Survey data from Pew also tells us the pandemic resulted in a further uptick in parents’ reported observations of their kids using social media apps, with TikTok being the most prevalent.

One phenomenon affecting today’s internet-connected young people is the supercharged parasocial relationships—one where someone feels they know and are close friends with a celebrity or even a peer the adolescent doesn’t know well.

Parasocial relationships are different from the usual relationship in that they are one-sided. In many cases today, the person on the other end of the phone is making money from this connection.

While not novel—fans connected with movie stars and singers to sometimes unhealthy degrees in earlier decades as well—these relationships are possible on a grand scale thanks to social media and are even leveraged intentionally by marketers to grow profits.

Whereas in the past it might become mentally strenuous for a developing adolescent to compare their situation to others in their classroom, the internet allows for comparison with nearly everyone else in the world.

The phenomenon extends beyond famous celebrities, too, and young people can develop a parasocial relationship with someone they may recognize at school as well as other peers. These relationships can have benefits for followers, including modeling positive behaviors. Depending on their intensity, however, professionals caution that these relationships can have negative effects on mental health and can exacerbate existing mental health issues. Social media use by itself has been shown in psychiatric studies to worsen self-esteem and depression and increase stress and exposure to bullying.

More time spent online also means adolescents have joined the ranks of internet users for whom activity is tracked and used to direct advertisements, often preying on insecurities and desires to sell products and services.

Knowing when to see a professional about treatment

The National Institute of Mental Health recommends parents look out for several signs in their child, depending on age, to determine whether a medical evaluation makes sense:

- Tantrums and irritability

- Difficulty making friends

- Excessive worrying or fear

- Frequent stomachaches with no medical cause

- Sleeping too much or too little

- Struggling academically

- Struggling to sit still when not interacting with media

- Loss of interest in passions

- Engaging in risky behavior or self-harm

- Abusing substances like drugs and alcohol

If you or someone you know is experiencing an emotional crisis, thoughts of hopelessness, or suicidal thoughts, dial or text 988 to reach a professional at the Suicide and Crisis Hotline.

Story editing by Ashleigh Graf. Copy editing by Paris Close.

This story originally appeared on Sandstone Care and was produced and

distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.